A Home Video Vacation With 14 Classics Of Japanese Cinema

As an old stick-in-the-mud once observed: “I’ve been enough places and seen enough things to know that going places and seeing things is vastly overrated.” So, okay, the old stick in question was in fact me. But, in my own defense, the observation stems from annually being dragged each summer as a kid to some godforsaken place for the sole purpose, seemingly, of posing with my large-ish family in front of a picturesque place or edifying monument and then, on a very tight time schedule, quickly moving onto another site of interest for yet another photographic moment of family album filler. Ad infinitum, ad nauseam. As far as vacations go, then, I spent much of my childhood sharing an unspoken sense with my siblings, parents, and grandmother that we might have all preferred to simply stay home.

Which is why in my elder years I spend my “vacations” doing just that. Running errands, personal projects, biking, reading; there’s a whole heckuva lot to do at home or nearby while simply, and more importantly, not working. And even more importantly for the purposes of this article, it’s the “not working” part in particular that affords this “slightly obsessed” moviewatcher the opportunity to catch up on some slightly obsessive moviewatching.

This staycation I resolved to spend my two-week break from work watching a whole slew of masterworks of Japanese cinema I had let pile up, regretfully, for quite some time. All are home video releases from the Criterion Collection and, by accident or design, all happen to have been directed by one of the Big Three among directors of Classic Japanese Cinema: Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu.

This staycation I resolved to spend my two-week break from work watching a whole slew of masterworks of Japanese cinema I had let pile up, regretfully, for quite some time. All are home video releases from the Criterion Collection and, by accident or design, all happen to have been directed by one of the Big Three among directors of Classic Japanese Cinema: Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu.

By this point one might be asking oneself how this work-like scenario sounds any different from the unenjoyable vacations I described taking as a kid. Simple: unlike those more stressful childhood trips of yore, I’ve chosen this staycation for myself. So, if traveling by sight, sound, and imagination through the history, images, and drama of one of the most exotic locales on earth seems a less than ideal way of spending one’s vacation time, I can only hope that I can convince the skeptic below by recording a few stray thoughts – as guided by the three keenest eyes, minds, and souls to record, dramatize, and represent their corner of the globe – on each stop along My Japanese Staycation.

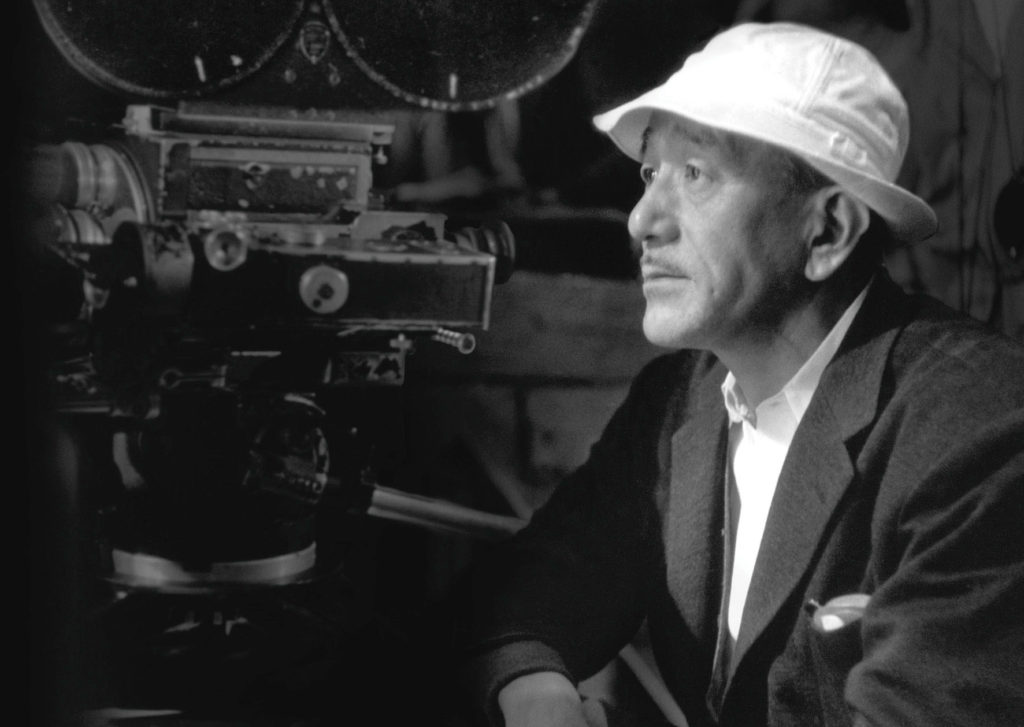

Akira Kurosawa

Our first “guide” to the cinematic wonders of Japan is undoubtedly the most recognizable among our pantheon of great Japanese directors. Though he came to directing much later than either Mizoguchi or Ozu, whose careers go back to the 1920s, the post-World War II emergence of Kurosawa as an internationally-prominent filmmaker – when his 12th feature, Rashomon (1950), was awarded the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival – also signaled a greater recognition for Japanese cinema worldwide. In a career whose later masterpieces include Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), and Yojimbo (1961), Kurosawa’s was a view of Japanese culture and history in bitter turmoil, where starkly heroic individuals – most frequently enacted by the great Toshiro Mifune (with whom Kurosawa made 16 films) – stand against the corruptions of society or the evils of human nature. But whether treating a historical subject in the Western genre-like samurai pictures for which he is most famous or in tension-filled contemporary thrillers like The Bad Sleep Well (1960) and High and Low (1963), the humanity of his protagonists and complexity of his situations always shine through, and his expertly-balanced narratives imbue scenes of action with depth and emotion. As the most “Western influenced” among Japanese directors, at least by reputation, Kurosawa refashioned Hollywood cinema and Western literature in a distinctly individualistic fashion, and, along with his stylistic mastery of the medium, later influenced directors as varied as Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, Francis Ford Coppola, and George Lucas.

Stray Dog

(Shintoho, 1949)

Setting out to make a police procedural inspired by the French pulp novelist Georges Simenon and the Hollywood docudramas of the late 1940s, Kurosawa instead deepened his focus to give an evocative and wide-ranging view of Japanese urban society immediately following the Second World War. Set during the American occupation, young police detective and war veteran Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) has his gun stolen during a terrible heatwave and, enlisting the aid of experienced detective Sato (frequent Kurosawa leading man Takashi Shimura), scours the black markets, low dives, dance halls, and back alleys of postwar Tokyo to capture the “stray dog” of the title (Isao Kimura), who is using the gun to commit murderous crimes. A fascinating counterpart to both Hollywood film noir and Italian neorealism of the period, Kurosawa offers a tantalizing glimpse of a society rebuilding itself after the devastation of war, along with dramatizing the personal choices each individual must make in either contributing to its betterment or in tearing it apart.

Throne of Blood

(Toho, 1957)

Kurosawa’s samurai adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth remains one of his most singular works, a film that is as dramatically exciting as it is thematically troubling. Set in feudal Japan during a period of civil war, samurai warrior Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) is rewarded for his prowess in battle by Lord Tsuzuki (Takamura Sasaki), but soon betrays and murders his master at the instigation of a spiritual prophecy (Chieko Naniwa) and the council of his ambitious wife, the terrifying Lady Washizu (Isuzu Yamada). Taking visual – and aural – inspiration from medieval Japanese Noh drama, Throne of Blood has often been referred to – by literary and film scholars alike – as the most successful translation of Shakespeare to film. Sacrificing, say, the climactic stage duel between Macbeth and Macduff in the play, Macbeth’s feudal Japanese equivalent of Washizu is instead screen-spectacularly riddled with hundreds of arrows – by his own warriors – when the second part of the spiritual prophecy is fulfilled and misty Spider Web Forest advances upon the gloomy fortress!

Hidden Fortress

(Toho, 1958)

Shot in Tohoscope and recorded in multi-directional Perspecta sound, Kurosawa’s great samurai adventure epic is possibly the director’s most purely enjoyable film. Set, again, during the civil wars of feudal Japan, lowly peasants Tahei (Minoru Chiaki) and Matashichi (Kamatari Fujiwara) are caught on the border between the warring Yamana and Akizuki clans, and are eventually enlisted – but more subtly manipulated – into unknowingly assisting exiled Akizuki general Rokurota Makabe (Toshiro Mifune) transport the disguised princess Yuki Akizuki (Misa Uehara) across enemy lines, along with – more importantly for the two peasants – the Akizuki clan’s fortune in gold, concealed in bundles of firewood. Though there are any other number of stories involving the rescue/protection of a princess (think of practically every Disney movie), the real innovation of the narrative is the decision to tell an epic story from the perspective of the most pathetic and powerless characters inhabiting that world, and the comically bickering peasant pair – wonderfully played by Chiaki and Fujiwara as sort of a Medieval Japanese Abbott & Costello – were an (acknowledged) influence on both the storytelling device and characters of the two droids C-3PO and R2-D2 from George Lucas’s original Star Wars (1977).

Sanjuro

(Toho, 1962)

A followup/possible sequel OR prequel to director Kurosawa and actor Toshiro Mifune’s lone ronin (i.e. “masterless samurai”) story Yojimbo (1961) is, at least reputedly, the “sunnier” side of adventuring heroics, but on further consideration actually proves to be a good deal more dark and sinister in its uncompromising view of the Kurosawan “man of action”. Assisting nine samurai restore their imprisoned lord’s rule from a corrupt group of officials, the nameless ronin (Mifune) again displays his quick wits and peerless skill with a sword in out-thinking, out-maneuvering, and then simply cutting down his opponents who, as in Yojimbo, are here absolutely legion. Scratching his beard stubble one second and then suddenly slashing through literal mobs of hired swords, the super fast-motion disposal of faceless hordes of less-skilled swordsmen proves almost comical at times, but, in one of the most astonishing sequences in a Kurosawa film, a seconds-long “duel” at the film’s end between the ronin and his most skilled adversary (Tatsuya Nakadai) proves a sobering conclusion for both the film and its characters, a geyser ripped from the felled opponent explicitly showing the lie to the light-hearted “adventuring” that precedes this image with the honor-bound figure lying in a pool of his own blood.

Red Beard

(Toho, 1965)

Although the title may not necessarily refer to the color of Dr. Kyojo Niide’s (Toshiro Mifune) facial hair – “red hair” having been a term used to describe Western medicine brought to Japan by Dutch surgeons – Akahige‘s (“Red Beard”) hairy chin and hirsute cheeks are indeed magnificent, and possibly none the less so if Asakusa Nakai’s widescreen black-and-white photography magically allowed us even a momentary glimpse of what we are left to only imagine, possibly, as a “reddish hue”. Formidable as that beard is, though, it is nothing compared to the man behind the beard, and Toshiro Mifune as Dr. Niide AKA “Red Beard” – in his final role for Akira Kurosawa – screen-embodies the fierce compassion, warmth, and depth of emotion that characterizes the great Kurosawan hero. Foregrounded in this 3-hour, 19th century-set tale of medicine and its practitioners, however, is the growth and education of Red Beard’s apprentice Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama), who in his encounters with figures like the selfless Sahachi (Tsutomu Yamakazi), the suffering Rokosuke (Kamatari Fujiwara), the insane and deadly “Mantis” woman (Kyoko Kagawa), and, finally, a rescued child prostitute, Otoyo (Terumi Niki), is well on his way to becoming a worthy “red beard” himself. As an equally worthy screen farewell to Kurosawa’s “popular” era of filmmaking, Red Beard leaves viewers with a palpable sense of longing for ways we could treat each other better and, in effect, improve the conditions in which we live.

Kagemusha

(Toho/20th Century Fox, 1980)

Returning to the Sengoku period (roughly the late 16th century) that was also the setting of his great samurai masterpieces Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), and The Hidden Fortress (1958), this bloody period of civil war between warring feudal lords receives its most devastating screen portrait in Kurosawa’s late-career masterpiece Kagemusha. The title, translated as “Shadow Warrior”, refers to the age-old practice of a lowly figure – such as, here, a condemned criminal – called upon to impersonate a great leader in a period of political vulnerability. Here, a thief who resembles the great leader of the Takeda clan (both played by Tatsuya Nakadai) is persuaded to assume the role of “Lord Shingen” when his real-life counterpart is assassinated by political rivals. An epic in every sense of the word, Kurosawa delivers battle scenes on a scale to rival those of Abel Gance’s silent-era masterpiece Napoleon (1927) and his use of color and spectacle are possibly unsurpassed in all world cinema. A solid decade in the making, from conception to filming, the production nearly bankrupted Toho Studios until American distributors 20th Century Fox, under the auspices of Kurosawa acolytes George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola for its international version, stepped in to provide funding for the film’s completion.

Ran

(Japan/France, 1985)

While I referred to his previous samurai Shakespeare adaptation Throne of Blood (1957) as “thematically troubling”, Kurosawa’s late 16th century version of Shakespeare’s King Lear is like a solid 2 hours and 40 minutes of staring into the abyss. Aging warlord Hidetora Ichimonji (Tatsuya Nakadai) rashly responds to a dream suggesting his imminent mortality and so divides his kingdom, three “castles” or war fortresses, between his sons Taro (Akira Terao), Jiro (Jinpachi Nezo), and Saburo (Daisuke Ryu). Saburo, ironically the son banished for honestly referring to his father’s plan as “senile”, is the only son to remain loyal to his father, and the great lord is soon reduced to wandering the wilds with his forces depleted and, eventually, solely accompanied through his increasing madness and a hostile, elements-raging environment by his comic “fool” (Shinnosuke Ikehata). To those familiar with its Shakespearean progenitor, Kurosawa here allows no heartwarming resolution to the tragedy – his Lear-figure isn’t even allowed a “comforting” death at the end of his travails – and indeed adds a deepening element in the terrifying figure of Lady Kaede (Mieko Harada), Taro’s wife and later Jiro’s paramour, whose secret agenda against Lord Hidetora’s clan moves through the narrative like a snake slowly coiling around its victim. (Her blood-soaked moment of simultaneous triumph and defeat rivals that of Sanjuro‘s for pure screen impact.) If Kagemusha is Kurosawa’s ultimate screen epic, Ran represents a near-cosmic level of tragedy stripping away at bonds of family, loyalty, and honor, and in their place presenting viewers with a hurtling world of chaos.

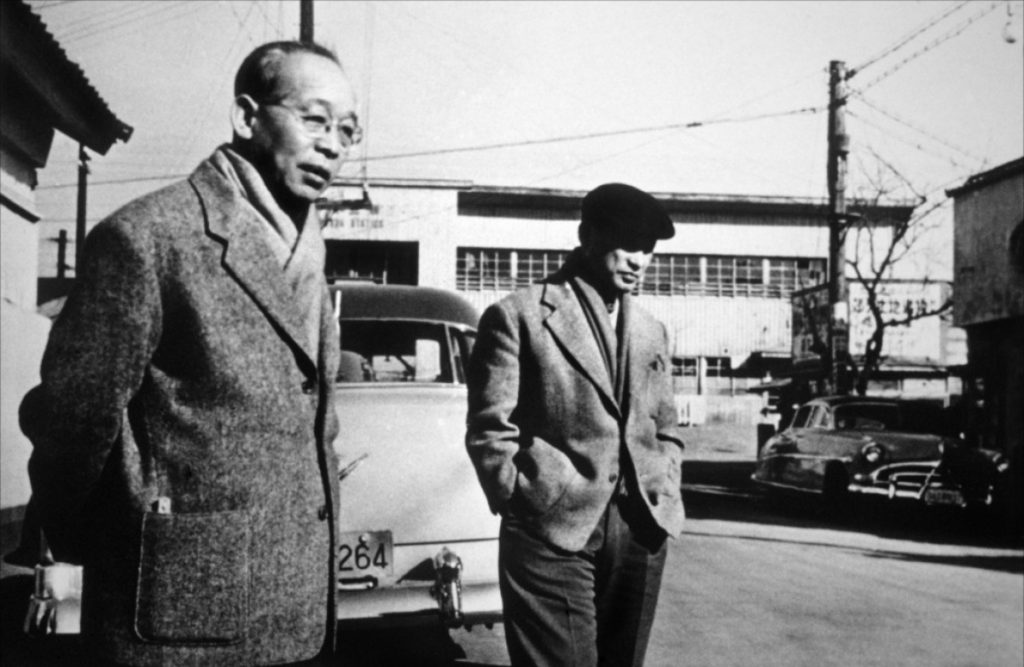

Kenji Mizoguchi

LEFT: director Kenji Mizoguchi

Possibly the greatest screen formalist to emerge out of any country, Mizoguchi’s is a film style that is virtually inseparable from his subject matter. Dealing with both contemporary and historical subjects in his films throughout his career, Mizoguchi’s unique view of Japanese culture and history had solidified by the mid-1930s – in the films Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion (both 1936) – into thematic and stylistic preoccupations associated, in Hollywood terms, with “the woman’s picture”. With their extended long-takes and meticulously-arranged mise-en-scene, Mizoguchi most frequently detailed the cruel plight of women in Japanese society, where strong heroines such as those enacted by favorite actress Kinuyo Tanaka (with whom Mizoguchi made 15 films) suffered exquisitely on-screen, but who persevered stoically through their terrible circumstances. Receiving much-belated recognition nearly thirty years into his film career – when his 1952 feature The Life of Oharu won an International Prize at the 1953 Venice Film Festival – the international acclaim he would soon enjoy was solidified by the cinematic one-two punch of Ugetsu in 1953 and Sansho the Bailiff in 1954. Unfortunately, Mizoguchi would not live long enough to fully enjoy his status as a world filmmaker – he would pass away two years later at the age of 58, shortly after completing 1956’s Street of Shame – but would leave cineastes the world over nearly slavering to more fully experience the subtly-composed images and awe-inspiring camerawork of his 60-film filmography (of which, more unfortunately, a scant 30 films now remain).

The Life of Oharu

(Shintoho, 1952)

Mizoguchi’s initial breakthrough to an international audience plays like the flip-side of Hollywood movies dealing with a “woman’s place” in society. Whereas in the films of, say, Douglas Sirk, a Hollywood director might have worked to wring every last soap opearatic drop from the story of a “fallen woman”, Mizoguchi’s narrative and stylistic strategies serve to deflate the drama in order to more deliberately explore the stages of her deepening circumstances. Set in the mid-Edo Period, roughly contemporary to the late 17th century, the court lady Oharu (Kinuyo Tanaka) is banished, along with her mother and father, for participating in an affair with a servant beneath her station (Toshiro Mifune, barely recognizable in a small role), who is promptly beheaded. A series of reversals occur for herself and her family, where they are forced to scrape a much-reduced living on the outskirts of the metropolitan center, and Oharu – after attempting suicide and then becoming mistress to a childless lord (Toshiako Konoe); providing him an heir before being cruelly forced to give up the child – is eventually sold into sexual slavery, becoming a high-priced courtesan – and even later a reluctant street prostitute – before ending up a wandering nun in her old age, begging for alms in the street. Bleak though that all may sound, the drama never manages to seem overdone (i.e., melodramatic) or exploitative, thanks in part to the sensitive performance of Tanaka as Oharu, but, more importantly, to the composed and pellucid presentation of a master director who never allows us to pity his female protagonist, but rather shows us her terrible plight in stark and uncompromising terms.

Ugetsu

(Daiei, 1953)

Based on a cycle of supernatural short stories from the late Edo period, roughly equivalent to the mid-/late 18th century, Mizoguchi reset his drama to a period two hundred years earlier, during the feudal civil wars (when Akira Kurosawa also set many of his samurai films), for an eerie tale of self-deception and failed responsibility against the backdrop of great social upheaval. As evocative of the devastation brought about by war as Kurosawa’s previously referenced, documentary-like thriller Stray Dog, Ugetsu foregrounds the circumstances of two peasant families – master potter Genjuro and his wife Miyagi (Kinuyu Tanaka), with their child Genichi; Genjuro’s brother Tobei (Sakae Ozawa), with his foolish dreams of become a samurai, and his neglected wife Ohama (Mitsuko Mito) – who together flee their village from rampaging occupying forces. Eventually becoming separated through their later experiences, Genjuro in particular has a romantic encounter with a beautiful spectral being, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo), in the ruins of a destroyed mansion that has devastating results for all parties. Carefully staged by Mizoguchi to suggest that the ghostly trappings of his tale are in fact not reality, but rather the hallucinations of a weak personality attempting to escape from reality, the drama of Ugetsu, as a fascinating complement to the more explicit feminist criticism of Oharu, can be taken as portraying the failure of the male psyche: where Tobei’s vainglorious visions of samurai power or Genjuro’s erotic fantasies blind both to the dreadful circumstances of the “here and now”, along with the attendant sufferings of those most near and dear.

Yasujiro Ozu

Enjoying an international reputation which now, in fact, eclipses all other other Japanese filmmakers – and, indeed, possibly eclipses all other film directors worldwide – the legacy of Yasujiro Ozu reveals both the triumphs and possibilities of popular filmmaking and, paradoxically, the sensitivities and nuances of a highly individualistic filmmaker. Encompassing a wide range of subjects and genre matter early in his career, covering everything from broad comedy to social protest films, by the mid-1930s – about 9 years and (an astonishing) 35 films into his career as director – Ozu narrowed his focus to the Japanese family with his first sound film, 1936’s The Only Son, and more specifically narrowed his focus to the trials and tribulations of the middle-class Japanese family after his 1949 masterwork Late Spring. With titles often evoking the passing of the seasons or a unique aspect of Japanese culture – including Early Summer (1951), The Flavor of Green Rice over Tea (1952), Equinox Flower (1958), and his last film, An Autumn Afternoon (1962) – Ozu spent this final portion of his career refining and revising a cinematic view of contemporary Japan that gently and lovingly detailed a rapidly-changing society’s equally rapidly-shifting values. Taking any moment from an Ozu film – the famous tatami-level camera, the eyeline shots of two characters, in conversation, speaking directly to the camera – reveals the difference between his comparatively unconventional filmmaking approach to almost any director in the world; however, in watching, the drama unfolds organically with his unique style in such naturalistic and disarming terms that a viewer can’t help feeling his might be the only way to properly make movies.

The Only Son

(Shochiku, 1936)

Ideally, I think the best way to watch Ozu’s movies would be to find as many as one can, representative of several different periods in his filmmaking career, and then watch them sequentially in the order in which they were made. The Only Son is not the earliest Ozu film I have seen – having, one time or another, also viewed his earlier silent film of A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) and his even earlier I Was Born, But... (1932) – but it does feel like a beginning, in a way, as an initial sense of quiet, family-oriented drama that builds inexorably, and yet unexpectedly, to moments of emotional release as artistically satisfying as they are gently realistic. Detailing the mother-son bond between a widowed mother, Tsune (Choko Iida), and a son, Ryosuke (Himori Shin’ichi), the drama unfolds with the mother toiling as a silk factory worker in order to pay for her son’s education; and their week-long meeting several years later, after a long period of separation, reveals the discontentment each feels, and has felt, in their respective roles. Notions of filial duty, self-sacrifice, and disillusionment are dealt with in narrative strains, like the woven silkscreen that here opens an Ozu movie for the first time, that suggest the complexity of their relationship even as both come to an understanding and acceptance of the other’s role and their continuing responsibility to each other. But still, in a heartbreaking coda where the mother breaks down emotionally outside the factory where she works, the sadness and ultimate tragedy of that relationship nonetheless persists, revealing that in Ozu films, as in life, there is no easy resolution between family members.

There was a Father

(Shochiku, 1942)

As the Criterion Collection includes this film and The Only Son as a set, and given their similar titles concerning a family relation, it is tempting to view each as a companion piece to the other. For me, then, There was a Father answers the previous Ozu film in terms of a family member who is absent. Where in The Only Son it is a father, in There was a Father it is a mother who is not present, the widowed figure of the father in the latter film (Ozu alter ego Chishu Ryu; the actor appeared in 52 of Ozu’s 54 films) burdened by his own sense of responsibility to a son, Ryohei (played by Harohiku Tsuda as a child and Shuji Sando as an adult), for whom he must act as father and mother to. Leaving the teaching profession after a tragedy on a school outing, mathematics professor Shuhei Horikawa (Ryu) sends his son to a boarding school in the provinces while he secures a position in Tokyo in order to pay for his son’s education. Detailing another long period of separation between a parent and child, the possibly greater tragedy of this latter family drama – where both reunite some 15 years later, only to be separated again, this time by mortality – is that both so keenly want to be together, but are continually separated by circumstances beyond each other’s control. Made during the Second World War, and commissioned by the Japanese government, there are clear propagandist overtones to a climactic moment when the elder Horikawa voices sentiments relating to sacrificing one’s personal needs to society (i.e., the war government), but Ozu’s ever-even style undercuts such notions through the subtlety of his drama and his realistic treatment of emotion.

Late Spring

(Shochiku, 1949)

Per our discussion of sequential viewing relating to Ozu films above, the last great development in the director’s film style and thematic concerns occurred with this film, 1949’s Late Spring, and watching this characteristic drama of a middle class Japanese family in relation to The Only Son and There was a Father is akin to experiencing another “new beginning” in Ozu’s films and in the treatment of his subject matter. Once again, in the single parent-situation existing between Professor Somiya (Chishu Ryu) and his grown daughter Noriko (Setsuko Hara; in the first role of many for Ozu), the characters are defined by the absence of a deceased parent/spouse, but here the questions relating to a parent’s duty to a child, or a child’s duty to the parent, are subtly shifted to account for the massive social and political changes Japan, as a country, had seen in the interim. Though one could hardly credit the connection given the cozy, insular view we are given in Late Spring of the Tokyo suburb of Kamakura, the film is in fact an exact contemporary of Kurosawa’s Stray Dog, and the more “modest” question of whether daughter Noriko should or should not, in effect, abandon her father for married life is just as marked by the postwar situation of an American-occupied Japan – through all its narrative threads relating to the possibilities of marriage or re-marriage; and even, in one character, the possibility of divorce – as is the more “dramatic” situation surrounding a stolen gun a few stops down Tokyo’s train line. As possibly Ozu’s most “pure” masterpiece, Late Spring equivocates between multiple views and options in postwar Japan, and finely-articulates both the joys and sorrows related to the choices ordinary people make.

Good Morning

(Shochiku, 1959)

Remaking his 1932 silent movie I Was Born, But…, Ozu’s most purely enjoyable family comedy follows a group of neighbors living in the suburbs of Toyko and the minor, comical social conflicts that arise in a tightly-knit community. Whether it’s the question of the wives’ social club and the (possible) mismanagement of its funds or the irritatingly persistent presence of door-to-door salesmen or the mysterious disappearance of a household’s entire supply of pumice stone, these little domestic “dramas” appear all the more comical given the director’s true-to-life handling; even revealing, in one particularly funny running gag (relating to the supposed properties of the above-mentioned pumice stone), that Ozu wasn’t above the occasional fart joke! Narrowing in on the Hayashi family – the translated title refers to the colloquial greeting one would most likely be greeted with on a Japanese street of Ohayu! (or “Good Morning”, depending on the time of day) – and the Hayashi children’s, Minoru and Isamu’s, small-scale “revolt” against polite society – and the empty “greetings” that go along with it – becomes a “silent” protest of their parents’ (Chishu Ryu, Kuniko Miyake) refusal to buy the family a T.V. set. (By film’s end, the Hayashi parents of course relent.) In its enjoyably meandering way – following kids as they walk to school, listening to the women gossip over some (perceived) social slight, joining dads as they drown their sorrows at the local watering hole – Good Morning ultimately seems to capture something ineffable about the rhythms and nuances of real life as really lived by real people.

Floating Weeds

(Daiei, 1959)

Another remake of an earlier silent film, this one of 1934’s The Story of Floating Weeds, 1959’s Floating Weeds is a ravishing look at love and loss, following a once-famous Kabuki actor, Komajura (Ganjiro Nakamura), and his now near-depleted acting troupe’s final tour stop in a remote seaside town. Years earlier, Komajura had fathered a son with a former mistress, Oyoshi (Ozu regular Haruko Sugimara), who now runs a small restaurant in the town, and the actor’s visit has as much to do with putting on a performance at the local theater as it does in revisiting the past. The son, Kiyoshi (Hiroshi Kawaguchi), who knows Komajura as an “uncle” but believes his actual father to be dead, gradually learns of his father’s identity, and the resulting revelation causes a permanent rift between all the characters who have found each other so many years later. In its sequential place among Ozu films, Floating Weeds at first glance appears to be out of place, especially in focusing on a character, the actor, who exists on the fringes of society and a fragmented “family” that is in fact not a family at all. But in relation to family members who are absent, as previously discussed in The Good Son, There was a Father, and Late Spring, these “floating weeds” of the acting troupe – especially in relation to Komajura’s present mistress, Sumiko (Machiko Kyo) – suggest the possibility of new types of family connections arising out of different social structures. That Komajura fails to re-connect with a loved one and his own son is, of course, the ultimate tragedy of the film, but Ozu, in his usual sly and subtle fashion, manages to wring a satisfying resolution, of sorts, where a drink proffered on a train ride to, possibly, nowhere becomes the hope of renewal on the next stop of the tragic actor’s endless tour.