A Time Travel Top Ten List

And so we come to the end of another movie year and the hard work the busy ZekeFilm contributors have put into reviewing and commenting upon this year’s notable releases has come to an end! 2015 awaits, but in the meantime it is time to put the last calendar year into cinematic perspective with ranked, ordered, and numbered lists through which viewers can come to grips with the best, worst, and middling selections that moviemaking in 2014 had to offer…

Which I very much wish I could do. Unfortunately, the limited number of new releases I have seen over the past 12 months, which have ranged from the extraordinary (Grand Budapest Hotel, Boyhood), the exceptional (Interstellar, Birdman), to at least one dud (Magic in the Moonlight – Sorry, Woody!), pretty much means that any list I would put together for 2014 would be, by numerical value alone (or its lack), ill-informed.

So! As I am all for creative solutions to insoluble problems, I have decided to time-travel a bit and, rather than reveal my ignorance of the current film year, put together a Top Ten list of notable releases from 50 years ago instead.

Without further ado, then:

Best Films Of… 1964!

10. A SHOT IN THE DARK

(The Mirisch Corporation, dir. Blake Edwards)

The second film in The Pink Panther series, released a few months after Peter Sellers made cinematic history in the original The Pink Panther (1963), finds impossibly-accented, bumbling bungler “Inspector Jacques Clouseau of the Sûreté” (Sellers) taking center stage in director Blake Edwards’ gaspingly hilarious farce, concerning the anti-Sherlock Holmes investigating a series of murders at a country estate. What follows are some of the most memorable set pieces in all film comedy—including Clouseau’s dramatic arrival at the estate and subsequent dunking in a fountain, Clouseau’s inept and sustained comic destruction of a billiard table, and culminating in a sequence where Clouseau, ‘disguised’ as a strumming guitar player, ventures into a nudist camp—as Clouseau sets out to prove that beautiful chief suspect “Maria Gambrelli” (Elke Sommer) is innocent despite all evidence to the contrary! Also introducing Herbert Lom’s twitching, pathologically Clouseau-hating “Commissioner Dreyfus” and Clouseau’s Judo-attacking servant, “Cato” (Burt Kwouk), this is one of the rare comedies without any dead weight or dead spots and, seen in an audience with a sympathetic audience (which was really your only option in 1964), plays to this day with beginning-to-end, wall-to-wall laughter. Sellers’ Clouseau is a masterful comic creation worthy of comparison to Chaplin’s Little Tramp, Buster Keaton’s pork pie hat-wearing misfit, and Harold Lloyd’s ‘glasses’ character, and A Shot in the Darkis undoubtedly Clouseau’s, and Seller’s, most comically successful vehicle.

The second film in The Pink Panther series, released a few months after Peter Sellers made cinematic history in the original The Pink Panther (1963), finds impossibly-accented, bumbling bungler “Inspector Jacques Clouseau of the Sûreté” (Sellers) taking center stage in director Blake Edwards’ gaspingly hilarious farce, concerning the anti-Sherlock Holmes investigating a series of murders at a country estate. What follows are some of the most memorable set pieces in all film comedy—including Clouseau’s dramatic arrival at the estate and subsequent dunking in a fountain, Clouseau’s inept and sustained comic destruction of a billiard table, and culminating in a sequence where Clouseau, ‘disguised’ as a strumming guitar player, ventures into a nudist camp—as Clouseau sets out to prove that beautiful chief suspect “Maria Gambrelli” (Elke Sommer) is innocent despite all evidence to the contrary! Also introducing Herbert Lom’s twitching, pathologically Clouseau-hating “Commissioner Dreyfus” and Clouseau’s Judo-attacking servant, “Cato” (Burt Kwouk), this is one of the rare comedies without any dead weight or dead spots and, seen in an audience with a sympathetic audience (which was really your only option in 1964), plays to this day with beginning-to-end, wall-to-wall laughter. Sellers’ Clouseau is a masterful comic creation worthy of comparison to Chaplin’s Little Tramp, Buster Keaton’s pork pie hat-wearing misfit, and Harold Lloyd’s ‘glasses’ character, and A Shot in the Darkis undoubtedly Clouseau’s, and Seller’s, most comically successful vehicle.

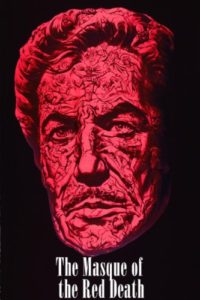

9. THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH

(American International Pictures, dir. Roger Corman)

AIP and Roger Corman’s sixth Edgar Allan Poe adaptation, and the fifth to star the immortal Vincent Price, is genuinely bizarre, proto-psychedelic, and perhaps the most artistically-accomplished genre horror movie of the mid-1960s. Photographed by Nicolas Roeg, who would go on to direct such visually-ravishing films asPerformance (1970), Don’t Look Now (1973), and The Man Who Fell to Earth(1976), the Red Death is brought to vivid life—no points for guessing which color dominates the film’s lush visual scheme—in this macabre medieval tale of debauched, Satan-worshiping “Prince Prospero” (Price) who feasts and parties in a locked ballroom as his kingdom succumbs to the titular virulent plague. Also combining elements from Poe’s short story, Hop-Frog, in which a dwarf jester (Skip Martin) takes violent revenge on an aristocratic tormentor (Patrick MacNee), Corman and screenwriters Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell round out the bare elements of Poe’s symbolic imagery with terrifying psychological elements only hinted at in the original tale. Comparisons to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) are inevitable, with the grim, hooded figure of the “Red Death” (John Westbrook) stalking each depraved step of the evil Prince—even turning the masque ball into a ghastly danse macabre at the film’s shocking climax—but really, Bergman himself might have hesitated to visualize a hallucination sequence where the virginal heroine is savaged by demons on an altar to Satan! (A scene, by the way, that was promptly cut by British censors.) A similarly shocking scene in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby was still 4 years away, but it’s not surprising to note that Corman was way ahead of the horror curve.

AIP and Roger Corman’s sixth Edgar Allan Poe adaptation, and the fifth to star the immortal Vincent Price, is genuinely bizarre, proto-psychedelic, and perhaps the most artistically-accomplished genre horror movie of the mid-1960s. Photographed by Nicolas Roeg, who would go on to direct such visually-ravishing films asPerformance (1970), Don’t Look Now (1973), and The Man Who Fell to Earth(1976), the Red Death is brought to vivid life—no points for guessing which color dominates the film’s lush visual scheme—in this macabre medieval tale of debauched, Satan-worshiping “Prince Prospero” (Price) who feasts and parties in a locked ballroom as his kingdom succumbs to the titular virulent plague. Also combining elements from Poe’s short story, Hop-Frog, in which a dwarf jester (Skip Martin) takes violent revenge on an aristocratic tormentor (Patrick MacNee), Corman and screenwriters Charles Beaumont and R. Wright Campbell round out the bare elements of Poe’s symbolic imagery with terrifying psychological elements only hinted at in the original tale. Comparisons to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) are inevitable, with the grim, hooded figure of the “Red Death” (John Westbrook) stalking each depraved step of the evil Prince—even turning the masque ball into a ghastly danse macabre at the film’s shocking climax—but really, Bergman himself might have hesitated to visualize a hallucination sequence where the virginal heroine is savaged by demons on an altar to Satan! (A scene, by the way, that was promptly cut by British censors.) A similarly shocking scene in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby was still 4 years away, but it’s not surprising to note that Corman was way ahead of the horror curve.

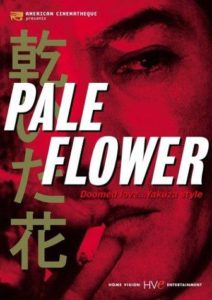

8. PALE FLOWER

(Shochiko, dir. Masahiro Shinoda)

With master Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu’s passing from cancer the previous year, and Akira Kurosawa in the midst of producing his mid-60s epic Red Beard, Japan’s oldest production companies Toho and Shochiko began depending on a younger stable of innovative directors, including Seijun Suzuki (Youth of the Beast, Gate of Flesh), Masaki Kobayashi (Harakiri, Kwaidan), and Hiroshi Teshigahara (Pitfall, The Woman in the Dunes), who by the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 received international recognition as a “New Wave” in Japanese filmmaking. Possessing only one film to his credit by this point (the same year’sAssassination), director Masahiro Shinoda offered a wildly unconventional take on the Yakuza film, Shochiko’s stock and trade through the late 50s and early 60s, with his brooding tale of a hitman (Ryo Ikebe) who embarks on a nonsexual, yet entirely perverse, relationship with a mysterious young woman (Mariko Kaga) over the high-stake tables of Tokyo’s illegal gambling dens. If Greek philosophers reduced all the world’s desires and fears to the bare elements of eros and thanotos, then this bleak, nihilistic noir—portraying themes that could only be hinted at had this been a contemporary Hollywood movie starring, say, Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer—is as close as a movie may ever come to showing two lovers not in love with each other but rather with the danger and doom they see in each other’s eyes!

With master Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu’s passing from cancer the previous year, and Akira Kurosawa in the midst of producing his mid-60s epic Red Beard, Japan’s oldest production companies Toho and Shochiko began depending on a younger stable of innovative directors, including Seijun Suzuki (Youth of the Beast, Gate of Flesh), Masaki Kobayashi (Harakiri, Kwaidan), and Hiroshi Teshigahara (Pitfall, The Woman in the Dunes), who by the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 received international recognition as a “New Wave” in Japanese filmmaking. Possessing only one film to his credit by this point (the same year’sAssassination), director Masahiro Shinoda offered a wildly unconventional take on the Yakuza film, Shochiko’s stock and trade through the late 50s and early 60s, with his brooding tale of a hitman (Ryo Ikebe) who embarks on a nonsexual, yet entirely perverse, relationship with a mysterious young woman (Mariko Kaga) over the high-stake tables of Tokyo’s illegal gambling dens. If Greek philosophers reduced all the world’s desires and fears to the bare elements of eros and thanotos, then this bleak, nihilistic noir—portraying themes that could only be hinted at had this been a contemporary Hollywood movie starring, say, Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer—is as close as a movie may ever come to showing two lovers not in love with each other but rather with the danger and doom they see in each other’s eyes!

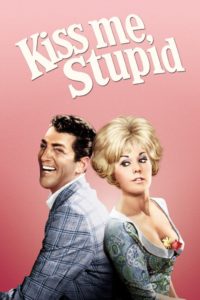

7. KISS ME, STUPID

(United Artists, dir. Billy Wilder)

“It happened in Climax, Nevada.” Director Billy Wilder and co-screenwriter I.A.L. Diamond’s follow-up to, in succession, Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment(1960), One, Two, Three (1961) and Irma la Douce (1963) has just never gotten the respect it deserves. This farcical tale concerns Lothario singer “Dino” (played by none other than Dean Martin) being stranded in a small town outside Vegas and taking overnight refuge at the house of piano teacher “Orville J. Spooner” (Ray Walston). Aware of the crooner’s lascivious reputation, the frantically paranoid host hires prostitute “Polly the Pistol” (Kim Novak) to pose as his absent wife, “Zelda” (Felicia Farr), and, naturally, comic complications ensue! Condemned in its own day as “smut” (by the Catholic Legion of Decency, among others), the film is unfortunately seen as rather tame by today’s standards… which, if you actually think about the film’s resolution, not to reveal the twists and turns of the plot, represents Billy Wilder’s darkest statement—even when compared to the director’s own Double Indemnity (1944) and Ace in the Hole (1950)—on small towns, bourgeois complacency, and All-American values. (To say nothing about the context of the film’s final, titular line!) Plus, if you’re willing to give it a chance, this admirably ‘naughty’ comedy contains some of Wilder & Diamond’s best one-liners—two foreign-born immigrants for whom English was not a first language, but who nonetheless wrote some of the best dialogue in Hollywood history—and breathlessly builds to some of their most memorable, funniest situations.

“It happened in Climax, Nevada.” Director Billy Wilder and co-screenwriter I.A.L. Diamond’s follow-up to, in succession, Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment(1960), One, Two, Three (1961) and Irma la Douce (1963) has just never gotten the respect it deserves. This farcical tale concerns Lothario singer “Dino” (played by none other than Dean Martin) being stranded in a small town outside Vegas and taking overnight refuge at the house of piano teacher “Orville J. Spooner” (Ray Walston). Aware of the crooner’s lascivious reputation, the frantically paranoid host hires prostitute “Polly the Pistol” (Kim Novak) to pose as his absent wife, “Zelda” (Felicia Farr), and, naturally, comic complications ensue! Condemned in its own day as “smut” (by the Catholic Legion of Decency, among others), the film is unfortunately seen as rather tame by today’s standards… which, if you actually think about the film’s resolution, not to reveal the twists and turns of the plot, represents Billy Wilder’s darkest statement—even when compared to the director’s own Double Indemnity (1944) and Ace in the Hole (1950)—on small towns, bourgeois complacency, and All-American values. (To say nothing about the context of the film’s final, titular line!) Plus, if you’re willing to give it a chance, this admirably ‘naughty’ comedy contains some of Wilder & Diamond’s best one-liners—two foreign-born immigrants for whom English was not a first language, but who nonetheless wrote some of the best dialogue in Hollywood history—and breathlessly builds to some of their most memorable, funniest situations.

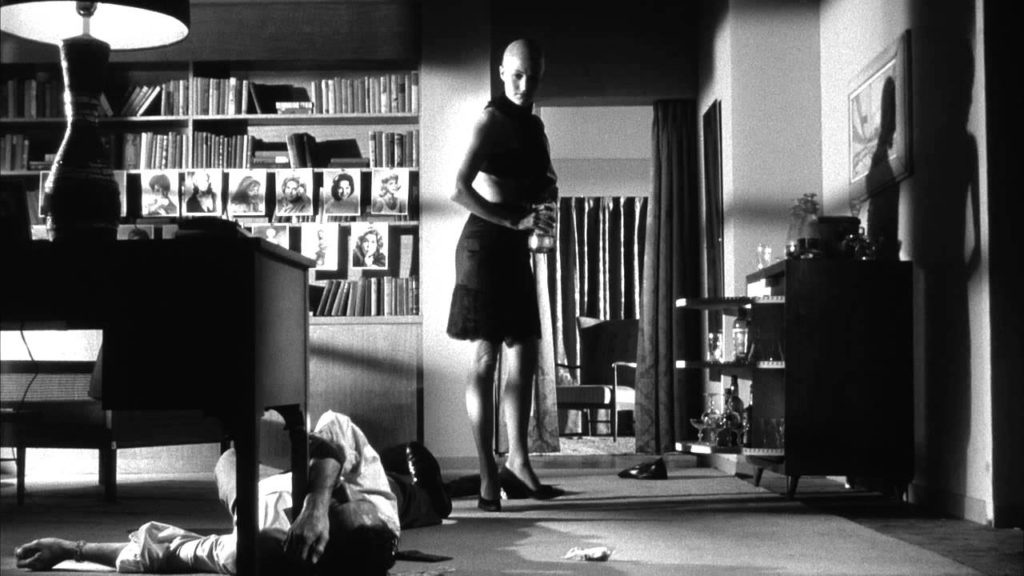

6. THE NAKED KISS

(Allied Artists Pictures Corporation, dir. Samuel Fuller)

Y’know, I just realized this list is getting rather transgressive in terms of its plot material and thematic elements. Well, I suppose filmmakers felt a bit more charged and empowered in 1964 to challenge the then-30-year-old Production Code—the tenets of self-censorship that Hollywood imposed upon itself in late 1933 at the behest of film producers and distributors—and, except when risky (and risqué) subject matter actually backfired at the box office (as was the case with the previous selection, Kiss Me, Stupid), a bit of envelope-pushing often translated into bigger receipts and potentially reaching a wider audience. Which unfortunately was not the case with director Samuel Fuller’s cinematic sucker punch,The Naked Kiss. Made for the Off-Hollywood Studio that had been known through the 30s and 40s as “Monogram Pictures,” the movie opened small, playing drive-ins and small arthouse theaters, before disappearing into cult obscurity… and before subsequently being rescued and restored for latter-day film appreciators by the good folks at the Criterion Company. (Yay!) A hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold (Constance Towers) leaves behind her former profession and takes residence in a mid-American smalltown, finding gainful employment as a nurse in a children’s ward, before being swept off her feet by a suave local aristocrat (Michael Dante) who is quite possibly too-good-to-be-true… which, just before the marriage, he ultimately, and shockingly, proves himself to be. Fuller’s hard-as-nails neo-noir is a worthy follow-up to his previous year’s Shock Corridor, still the high watermark of a go-for-the-gut vision that resulted in such uncompromising fare as The Steel Helmet (1951), Pickup on South Street(1953), and Underworld, U.S.A. (1961), and the direct cut that opens the movie of a bald prostitute having her wig ripped off and beating her pimp to death with a telephone receiver is nothing compared to the secret terrors that await that same hard-luck woman in idyllic Anywhere, U.S.A.!

Y’know, I just realized this list is getting rather transgressive in terms of its plot material and thematic elements. Well, I suppose filmmakers felt a bit more charged and empowered in 1964 to challenge the then-30-year-old Production Code—the tenets of self-censorship that Hollywood imposed upon itself in late 1933 at the behest of film producers and distributors—and, except when risky (and risqué) subject matter actually backfired at the box office (as was the case with the previous selection, Kiss Me, Stupid), a bit of envelope-pushing often translated into bigger receipts and potentially reaching a wider audience. Which unfortunately was not the case with director Samuel Fuller’s cinematic sucker punch,The Naked Kiss. Made for the Off-Hollywood Studio that had been known through the 30s and 40s as “Monogram Pictures,” the movie opened small, playing drive-ins and small arthouse theaters, before disappearing into cult obscurity… and before subsequently being rescued and restored for latter-day film appreciators by the good folks at the Criterion Company. (Yay!) A hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold (Constance Towers) leaves behind her former profession and takes residence in a mid-American smalltown, finding gainful employment as a nurse in a children’s ward, before being swept off her feet by a suave local aristocrat (Michael Dante) who is quite possibly too-good-to-be-true… which, just before the marriage, he ultimately, and shockingly, proves himself to be. Fuller’s hard-as-nails neo-noir is a worthy follow-up to his previous year’s Shock Corridor, still the high watermark of a go-for-the-gut vision that resulted in such uncompromising fare as The Steel Helmet (1951), Pickup on South Street(1953), and Underworld, U.S.A. (1961), and the direct cut that opens the movie of a bald prostitute having her wig ripped off and beating her pimp to death with a telephone receiver is nothing compared to the secret terrors that await that same hard-luck woman in idyllic Anywhere, U.S.A.!

5. BAND OF OUTSIDERS

(France, dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard’s seventh feature in four years (his A Married Womanwould be released later that year) is, from the latter-day perspective of the director’s often willfully frustrating and problematic style, undoubtedly his most delightful and purely entertaining effort. Detailing, in the loosest sense of the word, the casually three-cornered romance between the beguiling “Odile” (Anna Karina) and unemployed ne’er-do-wells “Franz” (Sami Frey) and “Arthur” (Claude Brasseur) as they ineptly embark on a life of crime, the complications, betrayals, and reversals of noirare added as almost an afterthought as homage to the director’s love of American Pulp Fiction. (This movie, more than any other I should add, directly influenced the Quentin Tarantino film of the same name; his act of cinematic theft even extending to the name of his production company, “A Band Apart,” which is taken from the film’s original French title, Band á part!) Rather, this is a film, even when compared to the director’s own body of work—as well as those made by the other meta-aware, third wall-breaking denizens of the French New Wave (Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette)—where the plot simply does not matter, functioning as a “clothesline” of sorts where Godard basically freed himself, narratively, to string together such sequential non-sequiturs as the famous “moment of silence” (where the trio sits around a cafe table and observes same; Godard dutifully turns off all ambient noise), “the Madison dance scene” (where they randomly perform an elaborate dance routine set to composer Michel Legrand’s R&B score), and the “nine minute and 37 second-run through the Louvre” (which is pretty self-explanatory; breaking, or so the narration tells us, a record previously set by “Jimmie Johnson of San Francisco”). In some movies it’s the story that carries an audience along, in others it’s the film’s style or visuals; here, though, it’s definitely the characters, whose company an audience will certainly wish to keep time and again!

French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard’s seventh feature in four years (his A Married Womanwould be released later that year) is, from the latter-day perspective of the director’s often willfully frustrating and problematic style, undoubtedly his most delightful and purely entertaining effort. Detailing, in the loosest sense of the word, the casually three-cornered romance between the beguiling “Odile” (Anna Karina) and unemployed ne’er-do-wells “Franz” (Sami Frey) and “Arthur” (Claude Brasseur) as they ineptly embark on a life of crime, the complications, betrayals, and reversals of noirare added as almost an afterthought as homage to the director’s love of American Pulp Fiction. (This movie, more than any other I should add, directly influenced the Quentin Tarantino film of the same name; his act of cinematic theft even extending to the name of his production company, “A Band Apart,” which is taken from the film’s original French title, Band á part!) Rather, this is a film, even when compared to the director’s own body of work—as well as those made by the other meta-aware, third wall-breaking denizens of the French New Wave (Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette)—where the plot simply does not matter, functioning as a “clothesline” of sorts where Godard basically freed himself, narratively, to string together such sequential non-sequiturs as the famous “moment of silence” (where the trio sits around a cafe table and observes same; Godard dutifully turns off all ambient noise), “the Madison dance scene” (where they randomly perform an elaborate dance routine set to composer Michel Legrand’s R&B score), and the “nine minute and 37 second-run through the Louvre” (which is pretty self-explanatory; breaking, or so the narration tells us, a record previously set by “Jimmie Johnson of San Francisco”). In some movies it’s the story that carries an audience along, in others it’s the film’s style or visuals; here, though, it’s definitely the characters, whose company an audience will certainly wish to keep time and again!

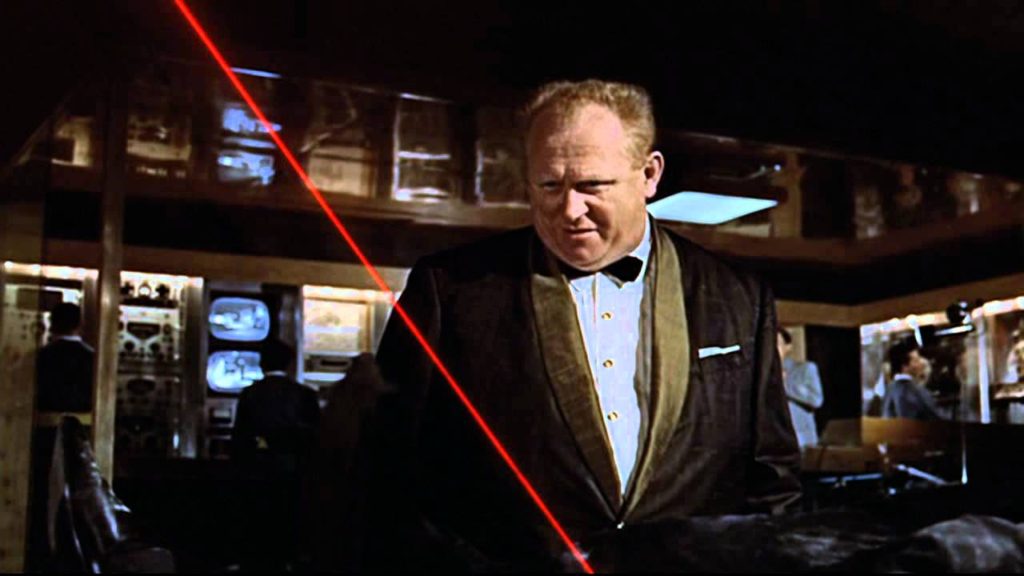

4. GOLDFINGER

(Eon Productions, dir. Guy Hamilton)

Often called “the best Bond,” Sean Connery’s third outing as the world’s most famous fictional spy arguably invented the modern-day action flick. From the gadget tricked-out Aston Marton DB5 with its ejector seat, revolving license plates, and smokescreen, to its charismatic titular villain (Gert Frobe) with his fiendishly clever plot to destroy the world’s wealth (i.e., irradiate Fort Knox’s gold supply in order to exponentially increase the value of his own gold stock – and I don’t even want to tell you how many viewings it took to work that one out!) I’d argue that just about every popcorn thriller made since has tried, and failed, to live up to its influence. Setting an unmatched tone with its opening image of Bond removing his underwater drysuit to reveal the suave superspy clad in a full-dress tuxedo(!), the style and sophistication of the series reached dizzying new heights courtesy of first-time Bond director Guy Hamilton’s emphasis on tongue-in-cheek mixture of action and humor, stunt coordinator Bob Simmons’ vividly-choreographed fight sequences, composer John Barry’s blaring, bold-as-brass score, and production designer Ken Adam’s visionary visualization of the holiest-of-holies behind American finance (i.e., Fort Knox itself). And what of mute bowler hat-decapitating manservant “Oddjob” (Harold Sakata), or the iconic image of a nude woman painted head to toe in gold paint (Shirley Eaton), or a Judo-thowing aviatrix who in promotional material for the film could only be referred to as “Miss Galore” (Honor Blackxman) or, indeed, the most (potentially) emasculating use of lasers in cinema history? “Do you expect me to talk, Goldfinger?” “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” Goldfinger is truly the gold standard of the series and, in the past 50 years, has consistently proved a nearly-impossible act to follow!

Often called “the best Bond,” Sean Connery’s third outing as the world’s most famous fictional spy arguably invented the modern-day action flick. From the gadget tricked-out Aston Marton DB5 with its ejector seat, revolving license plates, and smokescreen, to its charismatic titular villain (Gert Frobe) with his fiendishly clever plot to destroy the world’s wealth (i.e., irradiate Fort Knox’s gold supply in order to exponentially increase the value of his own gold stock – and I don’t even want to tell you how many viewings it took to work that one out!) I’d argue that just about every popcorn thriller made since has tried, and failed, to live up to its influence. Setting an unmatched tone with its opening image of Bond removing his underwater drysuit to reveal the suave superspy clad in a full-dress tuxedo(!), the style and sophistication of the series reached dizzying new heights courtesy of first-time Bond director Guy Hamilton’s emphasis on tongue-in-cheek mixture of action and humor, stunt coordinator Bob Simmons’ vividly-choreographed fight sequences, composer John Barry’s blaring, bold-as-brass score, and production designer Ken Adam’s visionary visualization of the holiest-of-holies behind American finance (i.e., Fort Knox itself). And what of mute bowler hat-decapitating manservant “Oddjob” (Harold Sakata), or the iconic image of a nude woman painted head to toe in gold paint (Shirley Eaton), or a Judo-thowing aviatrix who in promotional material for the film could only be referred to as “Miss Galore” (Honor Blackxman) or, indeed, the most (potentially) emasculating use of lasers in cinema history? “Do you expect me to talk, Goldfinger?” “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” Goldfinger is truly the gold standard of the series and, in the past 50 years, has consistently proved a nearly-impossible act to follow!

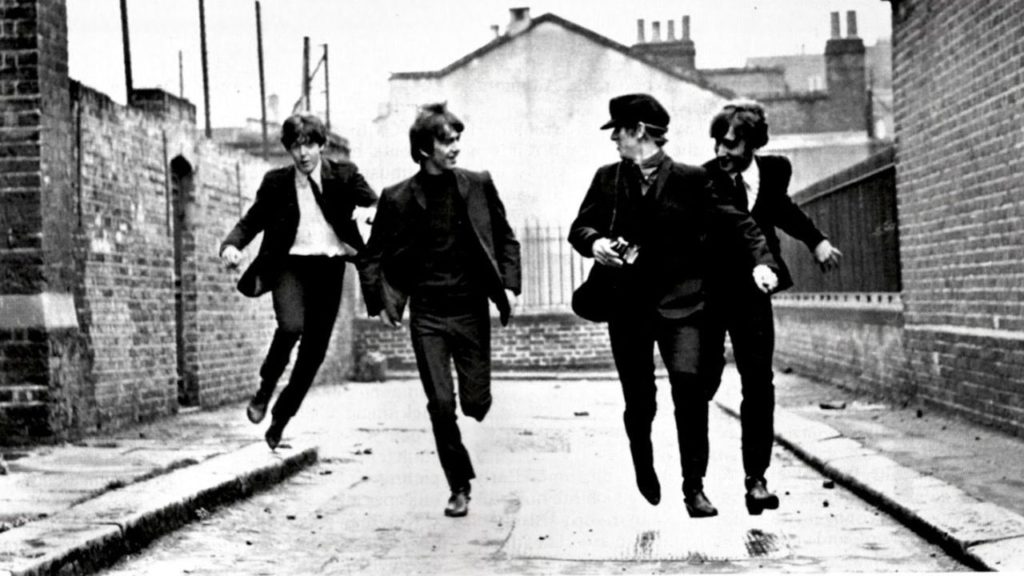

3. A HARD DAY’S NIGHT

(United Artists, dir. Richard Lester)

Strange to reflect that Beatlemania is now over 50 years old, but the passing of half a century has done absolutely nothing to dim the forever-youthful appeal of John, Paul, George, and Ringo! The Beatles’ first cinema outing, under the direction of American-born British expatriate Richard Lester, combines elements of the Marx Brothers, the French New Wave, cinéma vérité, the nascent concert film, and a tradition of off-the-wall British comedy whose roots are found in the Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers-starring radio program, The Goon Show, and extended through Beyond the Fringe, The Frost Report,Monty Python and others. Surreal, occasionally satirical, but best of all described by that grand British-ism of “cheekiness,” this is guerrilla comedy filmmaking at its finest, not only irrepressibly capturing Swinging London of the mid-sixties for all time, but also offering definitive visualizations of such timeless classics as “She Loves You,” “Can’t Buy Me Love” and the title tune – which was in fact written specifically for the film. The late Roger Ebert singled-out Ringo as “the best Beatles actor,” actually showing dramatic range in the charming sequence where he goes off on his lonesome, but I personally give points to George just for the exchange in the interview scene where he names his hairstyle “Arthur.” I should also mention comic actor Wilfrid Brambell for his “very clean” portrayal of “Paul’s grandfather,” a truly memorable comic creation who, according to Paul, is “a villain, a real mixer” and, as such, instigates much of the wonderful nonsense that showed a quartet of Merseyside Scousers taking the world by storm!

Strange to reflect that Beatlemania is now over 50 years old, but the passing of half a century has done absolutely nothing to dim the forever-youthful appeal of John, Paul, George, and Ringo! The Beatles’ first cinema outing, under the direction of American-born British expatriate Richard Lester, combines elements of the Marx Brothers, the French New Wave, cinéma vérité, the nascent concert film, and a tradition of off-the-wall British comedy whose roots are found in the Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers-starring radio program, The Goon Show, and extended through Beyond the Fringe, The Frost Report,Monty Python and others. Surreal, occasionally satirical, but best of all described by that grand British-ism of “cheekiness,” this is guerrilla comedy filmmaking at its finest, not only irrepressibly capturing Swinging London of the mid-sixties for all time, but also offering definitive visualizations of such timeless classics as “She Loves You,” “Can’t Buy Me Love” and the title tune – which was in fact written specifically for the film. The late Roger Ebert singled-out Ringo as “the best Beatles actor,” actually showing dramatic range in the charming sequence where he goes off on his lonesome, but I personally give points to George just for the exchange in the interview scene where he names his hairstyle “Arthur.” I should also mention comic actor Wilfrid Brambell for his “very clean” portrayal of “Paul’s grandfather,” a truly memorable comic creation who, according to Paul, is “a villain, a real mixer” and, as such, instigates much of the wonderful nonsense that showed a quartet of Merseyside Scousers taking the world by storm!

2. GERTRUD

(Palladium, dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Master Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s fourth film in as many decades—he passed away four years later in 1968 at the age of 79, still planning his long-unrealized screen biography of Jesus Christ—was like his previous film, 1955’s Ordet, based on a classic Scandinavian theatrical drama. Gertrud, from the 1906 play by Hjalmar Söderberg, concerns the title character (Nina Pens Rode), a former opera singer in early 20th century Stockholm, trapped in a loveless marriage to a city elder (Bendt Rothe), who embarks on a series of unfulfilling flirtations/affairs with a young pianist (Baard Owe), an old lover (Ebbe Rode), and a supportive friend (Axel Strøbye), before fleeing to Paris where it is revealed, in an epilogue taking place thirty years after the events of the drama, that she has devoted herself in the latter part of her life to the study and practice of psychology. Despite not having found love in her life, the character states in her final years that “love is the most important thing in life” and, having no regrets, concludes that “a life of disappointment is preferable to a life of compromise.” Dismissed in its original release as “overlong,” “mannered,” and “tedious” (despite Cahiers du cinéma placing it in its top-ten list for 1964) and ignored, and subsequently forgotten, upon its limited American release in 1965-66 (despite critic Andrew Sarris placing it in its top-ten list for 1966), Dreyer’s final feature is, perhaps even moreso than any film in his body of work, a litmus test for an audience’s tolerance of cinema that is more positively described as “meditative,” “profound,” and “moving.” Again, for those willing to challenge themselves, the passing of 50 years has made the hallmarks of Dreyer’s film style—extremely long takes, minimalistmise-en-scéne, and marvelously understated performances—look positively brave when compared to the filmmaking of today.

Master Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s fourth film in as many decades—he passed away four years later in 1968 at the age of 79, still planning his long-unrealized screen biography of Jesus Christ—was like his previous film, 1955’s Ordet, based on a classic Scandinavian theatrical drama. Gertrud, from the 1906 play by Hjalmar Söderberg, concerns the title character (Nina Pens Rode), a former opera singer in early 20th century Stockholm, trapped in a loveless marriage to a city elder (Bendt Rothe), who embarks on a series of unfulfilling flirtations/affairs with a young pianist (Baard Owe), an old lover (Ebbe Rode), and a supportive friend (Axel Strøbye), before fleeing to Paris where it is revealed, in an epilogue taking place thirty years after the events of the drama, that she has devoted herself in the latter part of her life to the study and practice of psychology. Despite not having found love in her life, the character states in her final years that “love is the most important thing in life” and, having no regrets, concludes that “a life of disappointment is preferable to a life of compromise.” Dismissed in its original release as “overlong,” “mannered,” and “tedious” (despite Cahiers du cinéma placing it in its top-ten list for 1964) and ignored, and subsequently forgotten, upon its limited American release in 1965-66 (despite critic Andrew Sarris placing it in its top-ten list for 1966), Dreyer’s final feature is, perhaps even moreso than any film in his body of work, a litmus test for an audience’s tolerance of cinema that is more positively described as “meditative,” “profound,” and “moving.” Again, for those willing to challenge themselves, the passing of 50 years has made the hallmarks of Dreyer’s film style—extremely long takes, minimalistmise-en-scéne, and marvelously understated performances—look positively brave when compared to the filmmaking of today.

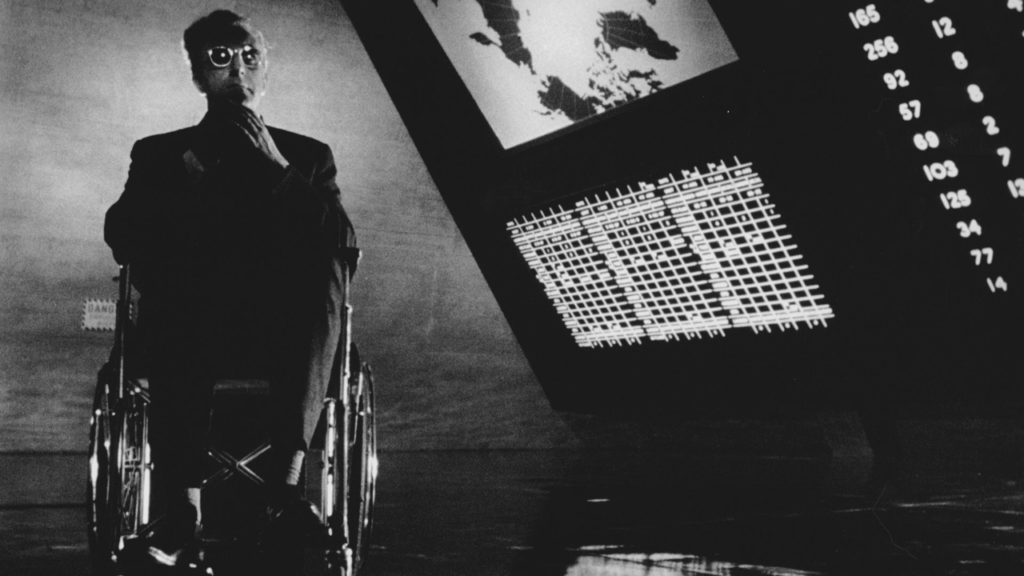

1. DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB

(Hawk Films/Columbia Pictures, dir. Stanley Kubrick)

And, finally, my top pick for all films released in 1964! Producer, co-writer, and director Stanley Kubrick traded on by-then over twenty years of political paranoia and fear of nuclear Armageddon to create his all-time masterpiece of black-as-the-prairie-on-a-moonless-night comedy. The results, co-written by Terry Southern, and starring an eclectic cast of performers including Sterling Hayden (“Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper”), George C. Scott (“General Buck Turgidson”), Slim Pickens (“Major T.J. ‘King’ Kong”), and, in a three-role triumph, Peter Sellers (“Group Captain Lionel Mandrake,” “President Merkin Muffley,” and wheelchair-bound, former Nazi atomic scientist, “Dr. Strangelove”), took a frighteningly-real scenario of “mutually-assured destruction” between the Cold War powers of the United States and the Soviet Union and ‘mined’ the nightmare situation (quite literally, as the film ends with Our Leaders absurdly arguing over a “mineshaft gap” as the surface world becomes virtually uninhabitable) for knockabout farce and belly laughs. From the phrase “Doomsday Device” to production designer Ken Adam’s expansive visualization of the “War Room” to Dr. Strangelove’s (involuntary) Nazi salute to Major Kong’s iconic “rough ride” on the tail-end of an atomic bomb, Kubrick cinematically treated the dark subject matter (and burlesqued its buffoonish perpetrators) with the contempt and irreverence it (and they) so richly deserved. So, as the bombs fell, mushroom clouds exploded, and Vera Lynn’s post-WWII anthem “We’ll Meet Again” played lushly over the soundtrack, audiences of 1964 were able to laugh at the unlaughable, providing comic relief on a literally global scale. The true power of film!

And, finally, my top pick for all films released in 1964! Producer, co-writer, and director Stanley Kubrick traded on by-then over twenty years of political paranoia and fear of nuclear Armageddon to create his all-time masterpiece of black-as-the-prairie-on-a-moonless-night comedy. The results, co-written by Terry Southern, and starring an eclectic cast of performers including Sterling Hayden (“Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper”), George C. Scott (“General Buck Turgidson”), Slim Pickens (“Major T.J. ‘King’ Kong”), and, in a three-role triumph, Peter Sellers (“Group Captain Lionel Mandrake,” “President Merkin Muffley,” and wheelchair-bound, former Nazi atomic scientist, “Dr. Strangelove”), took a frighteningly-real scenario of “mutually-assured destruction” between the Cold War powers of the United States and the Soviet Union and ‘mined’ the nightmare situation (quite literally, as the film ends with Our Leaders absurdly arguing over a “mineshaft gap” as the surface world becomes virtually uninhabitable) for knockabout farce and belly laughs. From the phrase “Doomsday Device” to production designer Ken Adam’s expansive visualization of the “War Room” to Dr. Strangelove’s (involuntary) Nazi salute to Major Kong’s iconic “rough ride” on the tail-end of an atomic bomb, Kubrick cinematically treated the dark subject matter (and burlesqued its buffoonish perpetrators) with the contempt and irreverence it (and they) so richly deserved. So, as the bombs fell, mushroom clouds exploded, and Vera Lynn’s post-WWII anthem “We’ll Meet Again” played lushly over the soundtrack, audiences of 1964 were able to laugh at the unlaughable, providing comic relief on a literally global scale. The true power of film!

And just because a top-ten list is so very limiting, here are a dozen more selections from 1964 that could undoubtedly have served an admirable place to any film listed above!

Without further further ado, then:

Very Notable Mentions Of… 1964!

A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS (Italy/Spain, dir. Sergio Leone)

“Spaghetti”and “Western” found their destined place together in director Sergio Leone’s Clint Eastwood star-making feature, which didn’t receive international recognition until its release in the United States three years later.

MARY POPPINS (Disney, dir. Robert Stevenson)

Julie Andrews lost out on starring in that same year’s My Fair Lady to Audrey Hepburn, but Walt Disney’s greatest live-action musical became a timeless family classic and Miss Andrews found her signature role.

HUSH… HUSH, SWEET CHARLOTTE (20th Century Fox, dir. Robert Aldrich)

This follow-up to the previous year’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? has screen veterans Olivia de Havilland, Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, Cecil Kellaway and Mary Astor joining legendary star Bette Davis for some more Grand Guignol fun, this time in the Deep South.

BECKET (Paramount, dir. Peter Glenville)

Peter O’Toole is Henry II to Richard Burton’s Becket in this magnificent historical production detailing the falling-out between the English Monarch and his most trusted adviser when the former makes the latter the Archbishop of Canterbury.

THE AMERICANIZATION OF EMILY (MGM, dir. Arthur Hiller)

James Garner, Julie Andrews, James Coburn, and Melvyn Douglas star in writer Paddy Chayefsky’s satirical wartime comedy-drama about an amoral coward being mistaken for a hero on D-Day.

THE UMBRELLAS OF CHERBOURG (France, dir. Jacques Demy)

In one of her first films, the luminous Catherine Deneuve stars in director Jacques Demy’s eye-popping French New Wave musical, from a legendary score by composer Michel Legrand, in which all the dialogue is sung.

THE WORLD OF HENRY ORIENT (United Artists, dir. George Roy Hill)

Two teenage girls (Tippy Walker, Merrie Spaeth) stalk concert pianist “Henry Orient” (Peter Sellers; who was obviously having quite a year in 1964) as he romances a married woman (Paula Prentiss) in director George Roy Hill’s delightful coming-of-age comedy.

SÉANCE ON A WET AFTERNOON (UK, dir. Bryan Forbes)

Two would-be con artists, a forceful “medium” (Kim Stanley) and her weak husband (Richard Attenborough), get more than they bargain for when they concoct a plan to kidnap a child (Judith Donner), which the medium will conveniently “find,” in director Bryan Forbes’ atmospheric thriller.

TOPKAPI (United Artists, dir. Jules Dassin)

Blacklisted former Hollywood director Jules Dassin’s international production, starring Peter Ustinov, Melina Mercouri, Robert Morley, and Akim Tamiroff, puts every caper film made before or since (except perhaps for the director’s French-produced, 1955 noir, Rififi) to shame with the most elaborate jewel robbery ever captured on film.

THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA (MGM, dir. John Huston)

Richard Burton gives one of his booziest performances (no great stretch, perhaps) as a defrocked Episcopal priest in director John Huston’s adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ South-of-the-Border romantic drama, opposite down-to-earth hotelier Ava Gardner and prim-and-proper artist Deborah Kerr.

THE TRAIN (United Artists, dir. John Frankenheimer)

French Resistance fighter Burt Lancaster stars opposite Nazi Colonel Paul Scofield in director John Frankenheimer’s nail-biting wartime thriller, in which the Resistance attempts to stop the Nazis from smuggling priceless works of art out of France to Germany via the titular mode of transportation.

DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID (France/Italy, dir. Luis Buñuel)

Director Luis Buñuel’s first film made in France since 1930’s L’age d’or, starring Jeanne Moreau in the title role, gleefully exposes perversion and cruelty among the aristocracy as seen through the eyes of their servants; one of whom, the groom “Joseph” (Georges Géret), murderously mimics their behavior.

Happy 2015 from the mid-60s!