Hollywood’s Last Great Glamor Girl

As a four-year-old, the first movie my mom remembered seeing in a theater was Audrey Hepburn’s first Hollywood-starring role, as Princess Ann in Roman Holiday (1953), and the first movie my mom saw as a freshman in college – studying English, theater, and film – was Audrey Hepburn opposite Albert Finney in Two for the Road (1967). In between, the icon of film and fashion was my late mother’s favorite movie star, the Hollywood actress who personified style and glamor the entirety of her childhood. Indeed, such was Ms. Hepburn’s inescapable appeal for young girls of her generation that my mom recalled the actress’s distinctively glamorous shadow over almost all “formal” events during her youth, culminating in a high school prom which played Henry Mancini’s theme song from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), “Moon River”, on a seemingly endless loop and where the dance itself was a swirling sea of sleeveless gowns inspired by Hepburn’s earlier appearance in the title role of Sabrina (1954).

As such, though I lobbied to have the actress be the subject of the Admissions article for May, Audrey Hepburn’s birth month, I find that I actually can’t participate: thanks to my mom, I’ve seen most of Hepburn’s major roles, and those few of her films I haven’t seen probably aren’t worth “admitting” to, anyway. Considering the impact Audrey Hepburn had on films, fashion, style, and taste during the 50s and 60s – and even during her subsequent half-retirement into the 70s and 80s to focus on her family and high-profile charitable endeavors – it is tempting to think of the actress, the icon, the international “personality” as being one of the last, if not THE last, great female movie stars of the twentieth century.

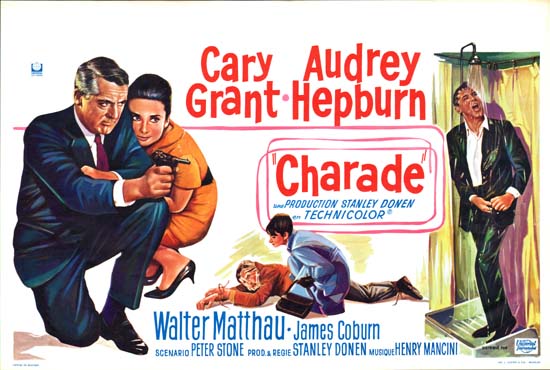

In any event, such was my mom’s argument while a high school English teacher and drama coach for her annual unit on “Classic Hollywood Cinema”. Yearly trotting out a battered, 16mm copy of her favorite film, Hepburn opposite a 24-years older Cary Grant – still suave and sophisticated in his late 50s – in the 1963 comic thriller Charade, the romantic comic stylings of sublimely witty sexual tension best exemplified for her, among later Classic Hollywood films, the light, seemingly effortless tone and star-driven power of screen “personality” that characterized the Golden Age of Cinema. Indeed, repositioning an argument that very well might be otherwise interpreted as a criticism, that Hepburn was frequently cast with leading men very much her senior – including Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina), Gary Cooper (Love in the Afternoon), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), Rex Harrison (My Fair Lady), and William Holden (also Sabrina; later Paris When it Sizzles) – might be taken by some as transparent evidence of casting sexism on the part of Old Hollywood, but for my mom merely proved that audiences simply wouldn’t have believed Hepburn on-screen with Troy Donahue, Tab Hunter, Doug McClure, or other such callow young performers of the day.

In any event, such was my mom’s argument while a high school English teacher and drama coach for her annual unit on “Classic Hollywood Cinema”. Yearly trotting out a battered, 16mm copy of her favorite film, Hepburn opposite a 24-years older Cary Grant – still suave and sophisticated in his late 50s – in the 1963 comic thriller Charade, the romantic comic stylings of sublimely witty sexual tension best exemplified for her, among later Classic Hollywood films, the light, seemingly effortless tone and star-driven power of screen “personality” that characterized the Golden Age of Cinema. Indeed, repositioning an argument that very well might be otherwise interpreted as a criticism, that Hepburn was frequently cast with leading men very much her senior – including Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina), Gary Cooper (Love in the Afternoon), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), Rex Harrison (My Fair Lady), and William Holden (also Sabrina; later Paris When it Sizzles) – might be taken by some as transparent evidence of casting sexism on the part of Old Hollywood, but for my mom merely proved that audiences simply wouldn’t have believed Hepburn on-screen with Troy Donahue, Tab Hunter, Doug McClure, or other such callow young performers of the day.

Winsome, plucky, and with an irresistible charm that can best be described as “elfin”…

…well, that’s how I also remember my mom whenever I happen to see an Audrey Hepburn movie. For both of their birth months – for, indeed, my mom was born 20 years and 1 day after Hepburn (and, sadly, my mom would follow Hepburn into the world beyond the screen a mere two months after the actress’s passing in 1993) – I would like to recognize Hollywood’s last great glamor girl and the subsequent generations of women she influenced with a particularly favorite Audrey Hepburn movie ‘quote’: “This is a ludicrous situation. I can think of a dozen men who are just longing to use my shower.

– Justin Mory

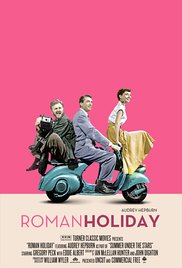

Roman Holiday

(1953, Paramount Pictures, dir. William Wyler)

by Erik Yates

This month’s Film Admission category of Audrey Hepburn was a wide open category of holes and regrets as I’ve missed much more of her body of work than I care to realize, so I decided to give Roman Holiday a go. Having been to Rome, and currently learning the Italian language, this film was a delight for me across the board.

This month’s Film Admission category of Audrey Hepburn was a wide open category of holes and regrets as I’ve missed much more of her body of work than I care to realize, so I decided to give Roman Holiday a go. Having been to Rome, and currently learning the Italian language, this film was a delight for me across the board.

The film proudly boasts in the opening credits that the entire film was shot in Rome, Italy and it is a highlight reel for tourists. From the Spanish Steps, the Pantheon, the Trevi Fountain, Castel Sant’Angelo, St. Peter’s Square, and more, Roman Holiday paints a highlights tour for all would-be travelers. The title credits also reveal a curious “Introducing Audrey Hepburn as Princess Ann” . Though she is credited with titles that predate this film in IMDb, this is apparently the one that Hollywood announced as her first that brought her to the forefront of pop culture. If this is true, then right out of the gate, Audrey is a vision and an example of a true movie star. From her girl-next-door smile, to her ability to create depth with just her eyes, Audrey perfectly fits the grace of a princess and the charm of a care-free spirit as her character sneaks away to enjoy normal life in all of its glory. From haircuts to dance parties off of the River Tiber, Audrey simply fits right in.

She is also every bit the equal of her co-star Gregory Peck. Written by famed blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, Roman Holiday delivers what Eli Wallach’s character in The Holiday called “gumption” when referring to the leading ladies of Hollywood’s “golden age”. Audrey certainly had that. To watch Audrey in 1953 playing an independent woman that is a match for her male leads in an age where that didn’t always match the culture is a vision to witness, especially seeing how women’s roles in film seem to be taking a step backwards in more modern films, even in the name of “feminism”. Audrey simply took hold of the role and brought a depth and grace to a character that still holds up today. The film also avoids the typical “happily ever after” and allows these characters to face the realities of their positions of Princess and reporter, respectfully. These are very different worlds that don’t often mingle at a personal level, but for a brief 2 hours we, like Princess Ann, get to take our own Roman Holiday, where anything is possible, even if it can never stay that way.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

(1961, Paramount Pictures, dir. Blake Edwards)

by Krystal Lyon

Oh boy, this will be a roller coaster. Here’s my real admission, I don’t like romantic films and I’m not a huge fan of Audrey Hepburn. (Happy Birthday to you Mrs. Hepburn!) To the people still reading this review, I know, I know, I’m a monster that was born without feelings. But give me a chance as I process the classic romance Breakfast At Tiffany’s.

Oh boy, this will be a roller coaster. Here’s my real admission, I don’t like romantic films and I’m not a huge fan of Audrey Hepburn. (Happy Birthday to you Mrs. Hepburn!) To the people still reading this review, I know, I know, I’m a monster that was born without feelings. But give me a chance as I process the classic romance Breakfast At Tiffany’s.

For the few that have yet to see Breakfast At Tiffany’s here’s a brief synopsis and some interesting facts. Holly Golightly, Audrey Hepburn, a upscale call girl with connections to the Mafia meets her new neighbor, washed up writer Paul Varjak, George Peppard. Inspired by Holly’s fantastic lifestyle of New York socialites, visits to Sing Sing Prison and a previous husband, Paul begins writing again. Love happens between the two but it’s complicated by the extravagant lifestyles of Holly and Paul and their lack of money. Breakfast At Tiffany’s is based on the novella by Truman Capote who claims he never liked the film and wanted Marilyn Monroe as the lead.

So let’s talk about Audrey Hepburn. She is dazzling! That opening scene, 5 AM New York in that black gown. It’s THE “Little Black Dress”! She stares at the finery of Tiffany’s which represents the life she wants, but she’s on the outside. Icon perfection! It’s the experience all women want in New York City. They want to look that fantastic and live the beautiful, devil-may-care life of Holly Golightly. Whether she’s in the black dress or playing a guitar in blue jeans, Audrey Hepburn exudes style and beauty. But should Holly Golightly be as classy as Audrey Hepburn?

Shouldn’t it be seedier? Isn’t that the “walk of shame” in the opening scene?

Breakfast At Tiffany’s comes across as a charming and fun romance or at least that’s how some see it. But Holly Golightly is a broken woman, a “wild thing”, “A phony who isn’t a phony because she believes it.” She’s an unsettled woman that’s hoping for a wealthy man to make her life right. The Chanel dresses and big hats hide her desperate state. Honestly, Breakfast At Tiffany’s is addressing something profound about shame, vulnerability and control. So was mainstream America not ready for a sullied view of Holly Golightly? Did Paramount class up Capote’s lead to make her acceptable for 1961 standards? Would Monroe have made a better Holly Golightly?

All these questions make me think that Breakfast At Tiffany’s is not honest, it’s the “phony”. Blame the culture and censures of the 1960’s but it feels false, make believe, pretend. While I think Hepburn is lovely and talented, I can’t admit that she is right for the part. Nor do I buy the chemistry between Hepburn and Peppard. There’s a rigid dichotomy at work here between the class and style of Hepburn and the truth in Capote’s story. All that to say, watch Breakfast At Tiffany’s for the style and the music. But in my opinion this film is “A Classic” because Audrey Hepburn looks good in a little black dress.

My Fair Lady

(1964, Warner Brothers, dir. George Cukor)

by Jim Tudor

It’s all quite easily explained, really… Growing up male in a household with no sisters and no parents compelled to expose me to every vintage musical under the sun, the three hour stagey spectacle My Fair Lady eluded me. The story is a simple one, straight out of “Pygmalion” by way of George Bernard Shaw: When aging bachelor and persnickety linguist Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison) takes a bet that he can’t turn a lowly cockney flower vendor (Audrey Hepburn) into a properly spoken lady of the time (clearly it’s the early 1900s England, give or take a decade), he gets more than he bargained for. So why is this film three hours long? Because in 1964, they didn’t know how to make musicals any shorter. Also, it’s adapted from the stage – at the then-major cost of $5 million for Jack Warner just to secure the rights – where running times are typically 3+ hours. Unbeknownst to me until now, My Fair Lady was quite the big deal, whatever the medium.

It’s all quite easily explained, really… Growing up male in a household with no sisters and no parents compelled to expose me to every vintage musical under the sun, the three hour stagey spectacle My Fair Lady eluded me. The story is a simple one, straight out of “Pygmalion” by way of George Bernard Shaw: When aging bachelor and persnickety linguist Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison) takes a bet that he can’t turn a lowly cockney flower vendor (Audrey Hepburn) into a properly spoken lady of the time (clearly it’s the early 1900s England, give or take a decade), he gets more than he bargained for. So why is this film three hours long? Because in 1964, they didn’t know how to make musicals any shorter. Also, it’s adapted from the stage – at the then-major cost of $5 million for Jack Warner just to secure the rights – where running times are typically 3+ hours. Unbeknownst to me until now, My Fair Lady was quite the big deal, whatever the medium.

Hollywood great George Cukor directs, infusing the film with an earnest and pure sense of class. The use of odd stillness mixed with singing during the black & white attired horse racing sequence is a particular inspiration. The upper class is depicted just proper and beautiful enough to be desirable, but not so much so that the proletarian roots of iconic Hepburn heroine Eliza Doolittle isn’t also viewed as viable (when the time comes). Yet, her poverty is never romanticized. To be sure, Cukor walks the line between merely transcending the confines of a filmed stage musical (one full of terrific, smart songs by Alan Jay Lerner & Frederick Lowe) and creating something worthy of a Best Picture Academy Award, which it indeed won. (As well as Best Actor for Harrison and Best Director for Cukor, this being his final major work. As for Hepburn? Not even nominated, perhaps due to the fact that her singing was notoriously overdubbed).

Although the first half of the film is entirely agreeable, I nonetheless had moments of wondering, “Why’d they give the Oscar to this??” By the end, I was wholly won over. (Maybe not to the notion of it beating out Dr. Strangelove and Mary Poppins, but certainly won over to the movie itself). And what an unexpected surprise that ending is…! If someone had tipped me off that My Fair Lady, as long as it is, has one of the most unresolved endings of all time, I wouldn’t have believed it. We may never know the final fate of Eliza and Henry and what exactly they’ve learned from this process of forced transformation, but we do come away knowing that he’s become accustomed to her face, where the rain in Spain mainly stays, and how to get to the church on time. Also, it just so happens that the date before this publishing, May 20, is Eliza Doolittle Day – so decrees The King! If everyone could celebrate, wouldn’t it be lovely?

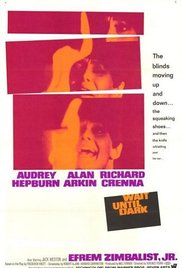

Wait Until Dark

(1967, Warner Brothers, dir. Terence Young)

by Taylor Blake

In high school, my mom and I began a quest to watch all of Audrey Hepburn’s movies. We both admired her sense of style and enjoyed the few movies we’d seen her in. So the summer I turned 15, while Dad and brother left town for a long baseball trip, we stayed up late every night to watch movies, including several Audrey films.

In high school, my mom and I began a quest to watch all of Audrey Hepburn’s movies. We both admired her sense of style and enjoyed the few movies we’d seen her in. So the summer I turned 15, while Dad and brother left town for a long baseball trip, we stayed up late every night to watch movies, including several Audrey films.

Over the next few years, we traipsed through Rome with Princess Ann, were charmed by Sabrina, fell in love with Holly Golightly, and even suffered in the convent with Sister Luke. Somehow, though, we never got around to meeting Susy Hendrix, Hepburn’s fifth and final Oscar-nominated role from 1967’s Wait Until Dark.

I’m happy to say we’ve finally made her acquaintance, and she didn’t disappoint. The film features a few Audrey movie motifs: a Henry Mancini score, swinging ‘60s fashion, and her first husband Mel Ferrer in the credits. However, almost all other details in Wait Until Dark break the Audrey mold. Instead of a rags-to-riches journey, Susy fights to overcome a disability. Instead of a romantic lead, she’s the heroine of a crime thriller.

Blinded after an accident, Susy has spent her last year relearning daily tasks like reading and cleaning. Aside from her new husband, Sam (Efrem Zimbalist Jr.), her only other aid comes from a young girl in their apartment building (Julie Herrod) who has a penchant for playing tricks on her. When Sam leaves town suddenly for work, she doesn’t think twice about it. That is, until visitors keep knocking on her door looking for a doll they say Sam has. Now, Susy begins to ask questions: Why do these visitors want the doll? Who is telling the truth? And, perhaps most importantly, where is that doll?

Most of Audrey’s iconic roles are women at the precipice of life changes, making decisions about their relationships and futures. All Susy wants is to live through today. Instead of relying on charm, Susy depends on her wits, and she proves to be sharper and sassier than the trio of doll thieves (Alan Arkin, Richard Crenna, Jack Weston) gives her credit for. Aside from Audrey’s performance, Wait Until Dark stands out for its twisting plot and a few moments of genuine fright. Clever breadcrumbs lead to the tense climax, when a malicious Arkin almost steals the show.

Full disclosure: Mom and I are still working on finishing Audrey’s résumé, but we’ll both pause to recommend this entry in her canon.