Disturbing Mexican Classic Asks, “Who are the Bad Hombres?”

DIRECTED BY FELIPE CAZAL/SPANISH/1976

BLU-RAY RELEASE DATE: MARCH 14, 2017/THE CRITERION COLLECTION

It’s always a nice surprise to come upon a completely unfamiliar film that is in fact a seminal entry in its national cinema history. It’s all the more surprising, upon first viewing, to find oneself a bit stunned by that designation.

Such is the case with my recent exposure to filmmaker Felipe Cazal’s 1976 Canoa: A Shameful Memory. Being admittedly unfamiliar with most Mexican cinema outside of crossover faves Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuaron and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu (the former two participate on this disc’s bonus features), a large amount of ignorance must be pleaded. But that said, the film’s predominant static, faux vérité quality did prove testing.

Based upon actual accounts of a 1968 lynch mob assault on a small group of visiting University of Puebla students in the humble village town of Canoa in Mexico. Cazal’s film cultivates no shortage of dread.

The screenplay, a daft work in its own right, courtesy of Tomás Pérez Turrent, accomplishes this upfront, opening in a city room as a reporter receives breaking details of the incident. After several minutes of frantic details, we then see disturbing footage of the violence itself, albeit through the distancing filters of black and white, and silence. Eventually, we will be hit with full impact.

Cazal’s film is, in terms of narrative audacity, an admirably odd duck. Experimental at its core, Canoais a bold genre-hopper, remaining absolutely tonally consistent all the while.

Eventually, it lands in what could be considered a horror movie-esque category, although not the kind of horror film that could ever be sequelized or remade. With historical senseless paranoia fueling the attack on these supposed Communists (they’re not Communists) the story is more evocative of the true horror of 2012’s The Act of Killing. Yet, it’s a winding and form-shifting path that eventually takes us to the bloody conclusion. The opening minutes, with the reporter on the phone, play as though it will be a newspaper film. Instead, that character disappears from the film.

Following the disturbing black & white attack footage, the film switches gears, jumping back in time to before the students ever set foot in their destination of Canoa. They seem an innocent and lively bunch of guys, simply eager for a little travel and hiking. Having just seen their future, one of mangling and maiming, the rest of the narrative carries a considerable amount of dread as we make our way to that point.

Utilizing a fourth-wall breaking style of vérité realism told via longwinded and long-lensed static shots, these naive would-be nature lovers inch their way closer to their unjust fate. Whether one is familiar with the actual “shameful memory” which the film is about, one knows all one needs to know after the first two sequences.

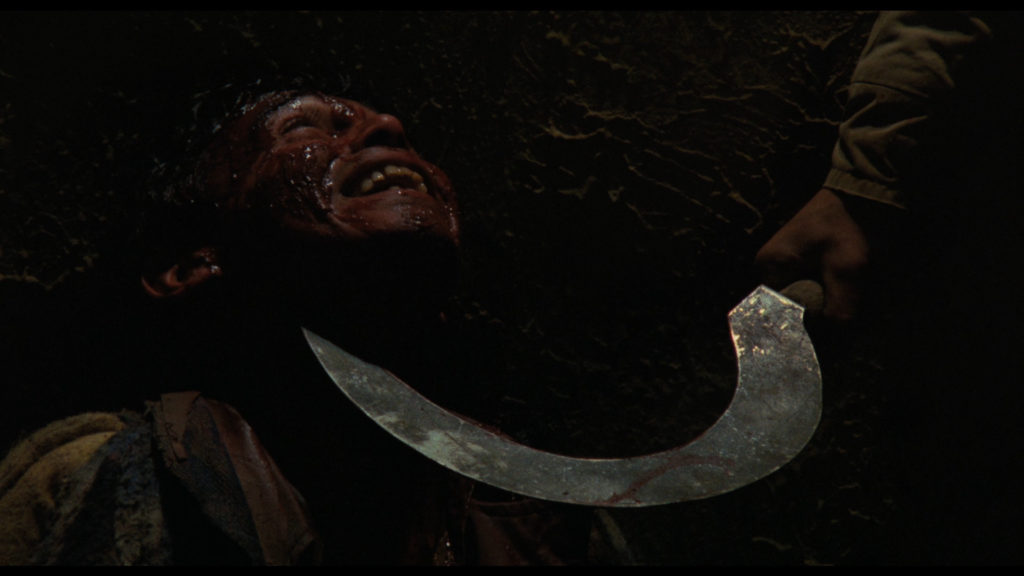

Following eighty-plus minutes of static documentary-style presentation of information, history, and varying opinions, the stage has been set for what can be described as a grindhouse shocker of a finale. The cinematic style abruptly switches into a bloody and confrontational mode, utilizing quick cuts and explosive gore. It’s a visceral and impactful sequence, one that understandably sent its local 1976 audiences reeling from the theater.

It’s structural surehandedness is Canoa‘s greatest attribute, sharply followed by its social and political immediacy. Released only eight years following the real life incident upon which its based – a lesser known incident that was the harbinger of a much larger massacre only a few weeks later – the damning impact of the film couldn’t help but resonate. Both del Toro and Cuaron say as much in the Criterion bonus features.

Likewise, as such events fade from collective memory, one can grasp why Canoastruck a chord in its moment, but could fall beneath the radar for those elsewhere. Despite the testimony of Cuaron, del Toro and Criterion itself, a quick survey of several online lists of “Best Mexican Films” altogether fail to include Canoa (or much of anything older than 2000’s Amores Perros, although a few do go back to the 1940s). Yet, the message it imparts regarding the senselessness of xenophobia, the horror at the heart of intolerance and the insanity of blind religious fervor cut deeply. Unfortunately at the moment, in the U.S. and elsewhere, these messages hit home far more resoundingly than they ideally should. Clearly, these are not the ways to make any country great again.

Criterion’s presentation of this new 4K digital transfer looks pretty impeccable, particularly for a film of this era that probably has seen it’s share of wear and tear. Although it’s now cleaned up and looking nice, it retains that gruesome grainy 1970s look, complete with inky pools of shadowy blacks and oily, glaring complexions. Canoa is not a pretty picture, but that is most obviously by design.

The bonus features are few, but worthy: Guillermo del Toro speaks for a few minutes about the importance of the film, and in a separate piece, Alfonso Cauron, who had his mind blow by Canoaas a boy of fourteen, chats with the director for an hour. The printed essay is also very good, although I can take or leave the packaging artwork.

The memory of watching Canoais not one of shame, but rather one of shock. I may not be returning to it anytime soon, but it’s something to have experienced it. The big screen aside, this is the way to take this difficult trip.

This review originally appeared at ScreenAnarchy.com.