The Cinema Auteur of India Rewards Discovery

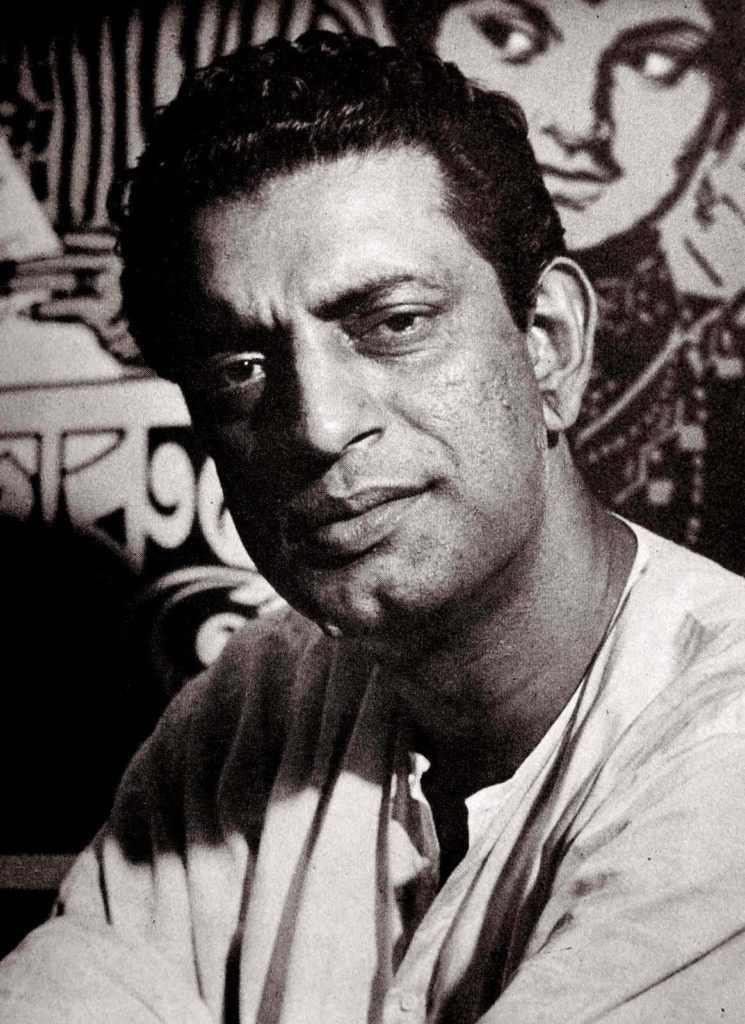

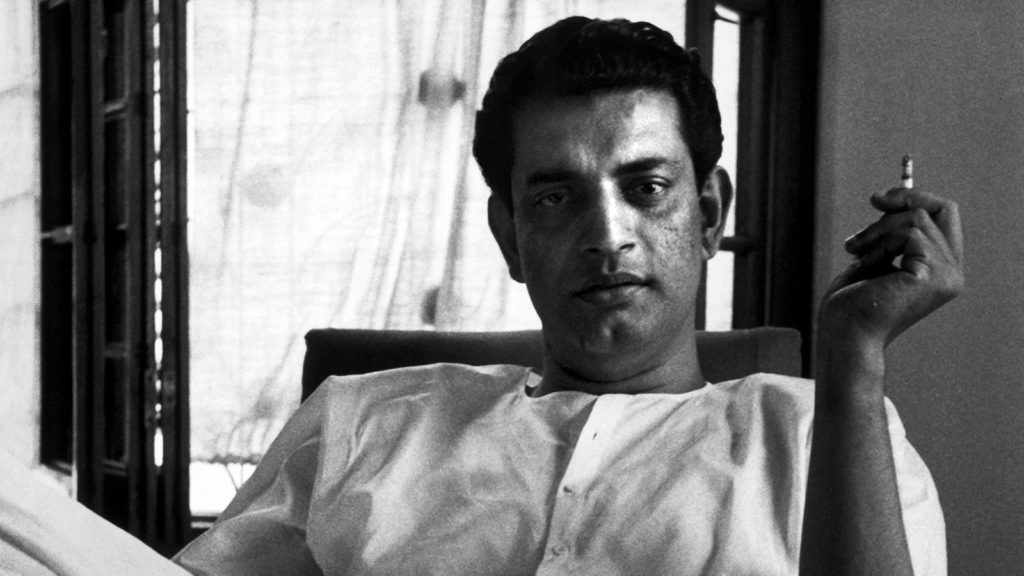

The word “humanist” gets thrown around a lot in cinema discourse. Used to describe filmmakers with compassionate worldviews who demonstrate an empathic attunement to human characters, it has the tendency to become a catch-all descriptor for any film that privileges quotidian human experience over explosions. Yet it seems to me that Satyajit Ray is one of a handful of the preeminent 20th-century auteurs, along with Ozu and De Sica, who truly warrants the label.

The word “humanist” gets thrown around a lot in cinema discourse. Used to describe filmmakers with compassionate worldviews who demonstrate an empathic attunement to human characters, it has the tendency to become a catch-all descriptor for any film that privileges quotidian human experience over explosions. Yet it seems to me that Satyajit Ray is one of a handful of the preeminent 20th-century auteurs, along with Ozu and De Sica, who truly warrants the label.

Ray’s films are deeply humane, openhearted illustrations of ordinary people negotiating the vagaries of life. They are concerned with the tensions and rifts between cultural tradition and modernity, fading attitudes and emergent ones, and collective and individual morality. They are measured and complex, treating their characters as three-dimensional social agents who are irreducible to any symbolic function. And like the neorealist lineage of filmmaking they inherit, they sensitively address the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

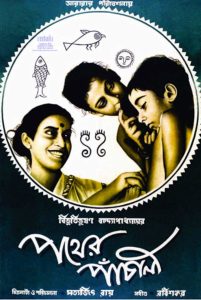

Ray’s debut feature, Pather Panchali (1955), is exemplary of the director’s sensibility. Based on a classic bildungsroman novel, it chronicles the experiences of a boy and his family living in a poor Bengali village. Owing much to the Italian neorealists whom Ray studied during his time in Europe in 1950, the film uses a cast of largely nonprofessional actors and unfolds with an unvarnished, quasi-documentary realism that focuses attention on social milieu rather than narrative dramatic incident. Pather Panchali was integral in establishing a new wave of realist cinema in post-colonial India that countered the formulaic excesses of Bollywood. When it screened in competition at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, it won the inaugural Best Human Document award and secured a spot for Indian cinema on the international stage. By the time the subsequent entries in the “Apu Trilogy” came along – Aparajito in 1956 and The World of Apu in 1959 – Ray and the national cinema he helped rejuvenate had become formidable.

Ray’s films are deeply humane, openhearted illustrations of ordinary people negotiating the vagaries of life.

In addition to directing thirty-six films over his career, documentaries and shorts among them, Ray also had ample experience in illustration, advertising, fiction writing, composing, and calligraphy. His multidisciplinary skills carried over to his films, many of which he not only directed but wrote, produced, cast, and scored. Ray’s diverse and prolific artistry attests to a filmmaker who believed in the power of personal expression and all the forms it could take. While his films became more eclectic in style from the mid-1960s onward – an output encompassing musical fantasies and science-fiction – they never lost the profound, anchoring humanity that comprised the bedrock of his early work. From Pather Panchali to his swan song, The Stranger/Agantuk (1991), Ray’s films evince an artist at once rooted in the societal textures of Indian life and immersed in a globalizing world, oriented toward both the traditional arts and letters of his formative years and the evolving 20th-century art-film landscape of which he became an esteemed contributor. Unassuming, lucid, lyrical, and yes, “humanist,” Ray’s films reaffirm the cinema’s unique capacity to generate empathy by bringing us just a little closer to the lives of others.

– Jonathan Leithold-Patt

Three Apus in Four Star Video Heaven: A Ray-membrance

by Justin Mory

For this rare “first exposure” submission to “Film Admissions”, this middle-aged contributor will have to go back approximately twenty years to recall movie-watching circumstances post-high school. Raised on silent and post-silent comedy (particularly Buster Keaton, Laurel & Hardy, and Our Gang), TV of my parents’ generation (‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s sitcoms, mainly), and Classic Hollywood movies of the ‘30s and ‘40s – the grand guignol screwball Arsenic and Old Lace (’44) and the colorful swashbuckler The Adventures of Robin Hood (’38) were early favorites – the world of cinema outside the United States and Hollywood remained one great Admission. Following my mother’s death in 1993, during my second year of high school, the restlessness, grief, and searching that accompanies the loss of a parent inspired a wider exploration of movies beyond our domestic borders. Although I only knew two foreign directors’ names – Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini – from my obsessive perusal of a dog-eared, spine-torn, scotch tape-bound copy of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide, I soon gained a familiarity with movie movements as far-flung as Italian Neo-realism, the French New Wave, and Japanese postwar cinema. From there, it was easy to draw a fuller if still sketchy movie map of the world.

Satyajit Ray must have come along slightly after discovering downtown Madison, WI’s Four Star Video Heaven; the “Heaven” apparently added after Chicago movie critic Roger Ebert called it so during a late-1980s visit there. Documentaries, indies, experimental – they also had the advertised “largest gay/lesbian-themed collection in the Midwest” (future advice columnist Dan Savage had once been store manager) – its selection certainly seemed dang-near comprehensive to a burgeoning cinephile (as a further parenthetical, Four Star’s core staff during the mid/late-1990s went on to found the Onion’s AV Club). For my purposes, its seven-foot tall, wraparound and room-length “Foreign Films” shelf – containing something like 2,000 alphabetized titles – entirely formed my early understanding of and continued exposure to a world cinema culture outside Hollywood. If it had a triangle-symbol after its capsule review in Leonard Maltin, Four Star had it in stock.

Armed with pizza delivery-tip money, and usually the latest two-for-one rental coupon cut out of the local Isthmus paper, I cut a wide viewing swath through the history and global geography of movies, certainly aided by an always inactive social life and an attending (and by now lifelong) avoidance of social responsibilities. Playing high priest to my movie religion of one, which then convened nightly into insomniac early hours of dawn in an attic apartment of my grandmother’s house, I could then marathon-view (“bingeing” had not yet entered the vocabulary) two, three, sometimes four movies at a sitting.

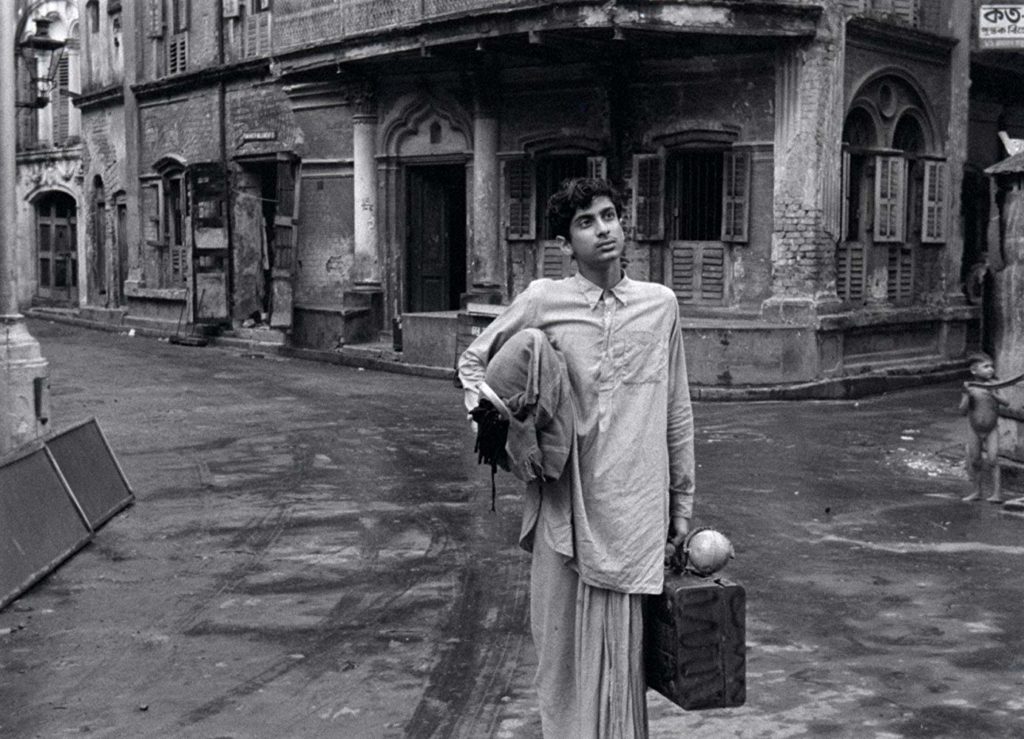

I must have rented/viewed Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1955-’59; comprising Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and The World of Apu) on the rare three-for-one coupon, and I wouldn’t be surprised if I viewed them all – madly, and inadvisably – in a row. I have gone on at such length at my circumstances of viewing them in this discursively first-person account that I can scarcely recall my first-time reaction to them. Movies were simultaneously my religion, drug, lover, and life-substitute, so I imagine the real-life dimension to this unique trilogy struck me deeply. We follow the small boy Apu (who, by the way, inspired the name of the Kwik-e-Mart owner on The Simpsons) to manhood, witnessing the poverty of his upbringing, the unbinding of his tightly-bound family, the painful circumstances of his education, and finally his difficult transition to marriage and fatherhood. Following disaster, disease, and death, there is continued tragedy for Apu as we fully witness the struggles and heartache of his childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

If that sounds grim, it is in viewing decidedly not. Filled with poetic moments of joy – amplified by Ravi Shankar’s evocative sitar score (the composer and instrumentalist’s first international exposure) and shimmering black-and-white photography – Apu at every stage of its universal character’s growing awareness of the world and his place in it may not take the place of life in solitary viewing, but my best compliment to Satyajit Ray’s unassuming art – especially when viewed beyond the Apu Trilogy – is that it comes awfully close.

Finally, in thinking about my own circumstances and life – or lack of one – in relation to the distance and reserve of movie-watching, with all the odd avenues and blind alleys of obsessive cinephilia in between, this account may seem sad, pathetic, or even horrifying. (Hopefully, not boring. Or not too much, anyway.) However, from where I’m still sitting these many years later, more now at the rate of three or four movies watched per week as opposed to day, the Apu Trilogies of the world, sadly few and far between, make a lifetime of otherwise undifferentiated film-viewing worthwhile.

Pather Panchali

1955, Government of West Bengal, dir. Satyajit Ray

by Jim Tudor

“It feels like Steinbeck.”

“It feels like Steinbeck.”

In the sobering minutes immediately following a recent group viewing of Satyajit Ray’s debut film, 1955’s Pather Panchali, this was but one of the felt, insightful responses. John Steinbeck- that most lyrical of chroniclers of the early twentieth century American experience, was connecting to a tale of Bengal village family struggle. The observation, intended as the high compliment as which it was received, continues to strike me as spot-on. This, despite the fact that Pather Panchai, a monumental Bengali film classic if there ever was one, is perhaps as far from American Western culture as one could get. Yet it is also a dusty dose of reality of the “real”; no trace whatsoever of India’s “Bollywood” artifice machine.

Though routinely thought of as a coming of age story of the boy Apu, Pather Panchali, it turns out, is very much a woman’s tale. Delivering a heart-wrenching performance of matronly misery, Karuna Bandopadhyay plays Sarbojaya, the mother of Apu and his older sister, Durga (primarily played by Uma Dasgupta, the “teenaged Durga”). Just as Sarbojaya’s character is the glue that hold the family together, Karuna Bandopadhyay (later known as Karuna Bannerjee) is the binding onscreen presence. Though Indian culture is often thought of as dominantly patriarchal, Pather Panchali presents from another view, ushering global audiences to empathize with a woman who’s put-upon for just about every reason she could be. As a wife, her dreamer of a husband (Harihar Ray) unceremoniously leaves their village to search for work elsewhere. He’s gone without a peep for months. As a mother, illness and extreme poverty assure her family’s status as outcasts, even in their undeveloped pocket of the modern world. Nosy neighbors express disapproval, village elders turn a blind eye, tragedy cannot be collectively grieved. All the while, an astonishingly aged and needy aunt, Indir Thakrun, played by a textured and worn Chunibala Devi, keeps coming around for sanctuary. Both a reoccurring burr to Sarbojaya and the undeniable face of one’s future in this place, Aunt Indir is a barely living cautionary tale of sorts; not just old and frail, but matter of factly ancient of days.

As the mystery of trains and power lines lingering across the nearby landscape prove irresistible to the rag-adorned village kids, we effortlessly understand their curiosities. Yes, there is a universal transcendence to Pather Panchai- this despite it being based upon a classic novel of the same name and of national importance, by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. But that said, there’s also plenty of native culture woven throughout. Such elements function as neither closed doors nor exoticism for sale to curious Western cinema goers. The tonal balance Ray strikes is something of a marvel – tragic without a hint of narrative oppression, absorbing without abandoning its identity. It’s Neorealist cinema brought forth through a lens of literary thoughtfulness and good old artistic passion. A very young and unknown Ravi Shankar brings forth a tremendously complimentary score.

Interestingly, the 1929 book is said to be the author’s first published effort- just as the motion picture adaptation is the well-rounded and accomplished Ray’s first film. Shot on a shoestring budget over the course of two years, Ray’s effort to bring Pather Panchai to life was understandably met with varieties of skepticism. Who is this guy? What will he make of the beloved novel? Why is it taking so long? Is this successful advertising agent glorifying/trading on Indian poverty? Ray, fortunately landed a masterpiece, the first in what is now known as “the Apu trilogy”, a monumental cornerstone in all of World Cinema.

Clearly, it was all meant to be- According to IMDb trivia, Ray attributed his success in the two year shoot “to three miraculous occurrences (or rather non-occurrences), referring to his cast by their character names: ‘One, Apu’s voice did not break. Two, Durga did not grow up. Three, Indir Thakrun did not die.’” When this sort of thing happens, allowing for a magnificent film, we say that “the movie gods were on the side of this production.” Though no one that I know of seriously ascribes to any such pantheistic belief system, the notion of a providential assist in bringing work such as this to a world starved for such pure empathy is something to take solace in. Ray understood that he owed the success of this film, and in turn, his subsequent career, to mysteries well beyond his control.

As for me and my own heretofore avoidance of the filmography of Satyajit Ray, it’s not for lack of knowledge of importance and legacy. The significance and collective admiration of Ray is unavoidable in cinephile circles. It was also not for lack of access to his films, as I’ve owned five of them, including the Apu trilogy, sight unseen for several years. Did I know these films would be enlightening, worthwhile, and enriching? I never doubted it. Yet somehow, I let them sit on the shelf for all that time. Perhaps, despite my own best efforts at cinematic inclusiveness, the presumed sitar-strained dirt huts of Ray’s Apu films were unappealing cultural and classist barriers that I didn’t care all that much about climbing beyond. Like François Truffaut famously and shamefully reportedly said about this film, “I don’t want to see a movie of peasants eating with their hands.” Truffaut later apologized, woke to his own uncovered ignorance. Though my own resistance was never so pronounced, I’ll nonetheless admit guilt on this front, and express many thanks to Jonathan Leithold-Patt for assigning us the “Film Admissions” topic of Satyajit Ray. What an opportunity this has been. These Steinbeck-ian peasants who eat with their hands have opened up not just the world of Apu, but the compelling sure-handed talent of Ray.

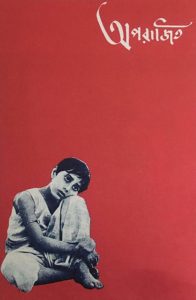

Aparajito

1956, Epic Productions, dir. Satyajit Ray

by Robert Hornak

My first ever Ray film was his first, Pather Panchali, years ago. My second ever Ray film is this one, his second. I’m watching them as fast as he made them, so give me time. In Aparajito, which means “the unvanquished”, the family has moved to the big city of Benares, where locals bathe in the Ganges to pay respects to Vishwanath and every movement of urban life is infused with a deep, ancient spirituality. Apu, though, is still pre-accountability, and dances on the edge of the mysterious, satisfying a wanderlust that once found its mark in the trees of Nischindipur but now in the sharp, sepulcher-like angles of a sprawling cityscape, running with the town boys through the crowds and ducking under oxen that roam free in mock commentary that for all his progress, man is still beholden to nature, the wild, the unpaved. And the intimacy that strung together poverty-stricken neighbors is traded for a cordial, unspoken rule of distance.

My first ever Ray film was his first, Pather Panchali, years ago. My second ever Ray film is this one, his second. I’m watching them as fast as he made them, so give me time. In Aparajito, which means “the unvanquished”, the family has moved to the big city of Benares, where locals bathe in the Ganges to pay respects to Vishwanath and every movement of urban life is infused with a deep, ancient spirituality. Apu, though, is still pre-accountability, and dances on the edge of the mysterious, satisfying a wanderlust that once found its mark in the trees of Nischindipur but now in the sharp, sepulcher-like angles of a sprawling cityscape, running with the town boys through the crowds and ducking under oxen that roam free in mock commentary that for all his progress, man is still beholden to nature, the wild, the unpaved. And the intimacy that strung together poverty-stricken neighbors is traded for a cordial, unspoken rule of distance.

Meanwhile, father plies his sermons and prayers down by the river, bringing in his pittance, his smiling, rural latitude disallowing the thought that the city itself, in the form of innumerable stairs at the water’s edge, could kill him, or that wolves lay in wait for his demise. His death triggers a retreat by mom and boy back to the simple life, and Apu learns in the most matter-of-fact way he’ll be training to be a priest. But his father’s trade only dampens his spirits – whereas enrolling in school, his own choice, allows a full plunge into all the disciplines, and he engorges on learning. Soon, after a Boyhood-like cut, he’s scholarship-bound to Calcutta for further studies – and leaving his mother behind to absorb a third loss after the death of her daughter (in Pather Panchali) and husband. The trilogy might be named for Apu, but the unvanquished of this title is mom.

The movie finds beauty everywhere: in the mundane glut of a narrow market, in the sunlit river that backdrops father’s ultimate collapse, in the purity of a flat plain leading back to simplicity, and anywhere there is room for a neo-realist embrace of poverty – never glamourized, always truthful. But what strikes me most, if you’ll forgive the crass indulgence, is that by the end, the film has become one of the all-time great doorway movies. So many doorways – characters passing through one, awaiting someone’s arrival through one, celebrating by running through one, ruminating on a fresh sin in the frame of one, etc. It can’t be by chance that Ray has so many pivotal emotional moments in the vicinity of a passageway to another perspective. The movie is that for us: a way to see thoughtfully through to a different way of life while still connected to that which is already familiar. One of the final shots of the film, Apu walking away from an old man who’s declaring the boy’s need to stay, and Apu stepping through a door that spills him back onto the trail to Calcutta, is about as poignant and direct a declaration of personal freedom as you’ll get.

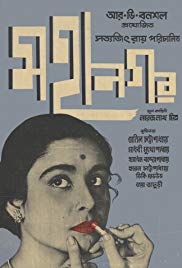

Nayak: The Hero

1966, R.D.Banshal & Co., dir. Satyajit Ray

by Jeffrey Knight

Up until the subject for this month’s Film Admissions was announced, I had seen only one Satyajit Ray movie, Pather Panchali. Now if you’re only going to see one movie by Ray, this is probably the one to watch, as it’s his first and probably best known of the bunch (though if you do see Pather I urge you to at least complete the entire Apu Trilogy, you won’t regret it). Ray made Nayak (The Hero) a decade after Pather’s release, and it’s a very different sort of movie, stylistically. Ray’s earliest films were heavily influenced by those of the Italian Neorealist school- like Rome: Open City or (especially) Bicycle Thieves. Nayak is slicker and more polished. It still shares Ray’s humanist outlook and the deliberate (though never boring) pacing of the earlier films.

Up until the subject for this month’s Film Admissions was announced, I had seen only one Satyajit Ray movie, Pather Panchali. Now if you’re only going to see one movie by Ray, this is probably the one to watch, as it’s his first and probably best known of the bunch (though if you do see Pather I urge you to at least complete the entire Apu Trilogy, you won’t regret it). Ray made Nayak (The Hero) a decade after Pather’s release, and it’s a very different sort of movie, stylistically. Ray’s earliest films were heavily influenced by those of the Italian Neorealist school- like Rome: Open City or (especially) Bicycle Thieves. Nayak is slicker and more polished. It still shares Ray’s humanist outlook and the deliberate (though never boring) pacing of the earlier films.

Uttam Kumar plays a movie star named Arindam Mukherjee. Mukherjee has been invited to Delhi to recieve some sort of prestigious award. He’s accepted the invitation at the last minute, so there’s no more time to get a flight, so Mukherjee has to take a long train journey to get there. Once on the train, he finds himself in the company of a young journalist named Aditi Sengupta, played by Sharmila Tagore (who appears in Ray’s Apur Sansar prior as Apu’s young wife). Aditi wants to increase the circulation of the woman’s magazine she edits, and thinks that interviewing the star will boost subscriptions. The two begin a conversation which, over the course of the journey, will reveal much more about Mukherjee to himself than the actor is ready to deal with.

At the start of the film, Mukherjee is on top of the world… mostly. He’s a big star, but there’s some concern about the box-office of his latest film. Add to that, newspapers are reporting that he had gotten into a drunken brawl at a club the night before- and that sort of scandal isn’t going to help his movie. Mukherjee isn’t that worried about it. He’s getting this award and is still idolized by millions. This will all blow over soon enough. On the train, however, between his talks with Aditi and his interactions with other passengers (there is an old man who is very critical of actors- especially actors who drink- and his criticism cuts Mukherjee close to the bone), old doubts and insecurities began to resurface. He’s getting this award, but maybe he doesn’t feel like he deserves any of it.

Mukherjee’s journey of self-discovery is told primarily through dream sequences and flashbacks. Flashbacks and fantasy! This is a far cry from the more naturalistic style that Ray used in the Apu Trilogy. Throw in the fact that you have a movie shot mostly on a set, complete with rear-projection, and employing actual working actors (as opposed to the ‘real people’ who featured heavily in Pather) and you have a movie that’s very distinct from Ray’s earlier work. Nayak began a period of Ray’s career that saw him working in a wide variety of genres and styles- musical fantasy, detective movies, and films that focused on contemporary life.

When Aditi and Mukherjee first meet, he asks her if she likes the movies. No, she confesses, because they aren’t realistic to her. Aditi doesn’t like how the stars in such movies are always presented as idealized godlike heroes. As one of those idealized heroes, Mukherjee has certainly profited from from the way movies present him to the world. At the end of his journey, however, he can also see clearly this hero’s feet of clay.

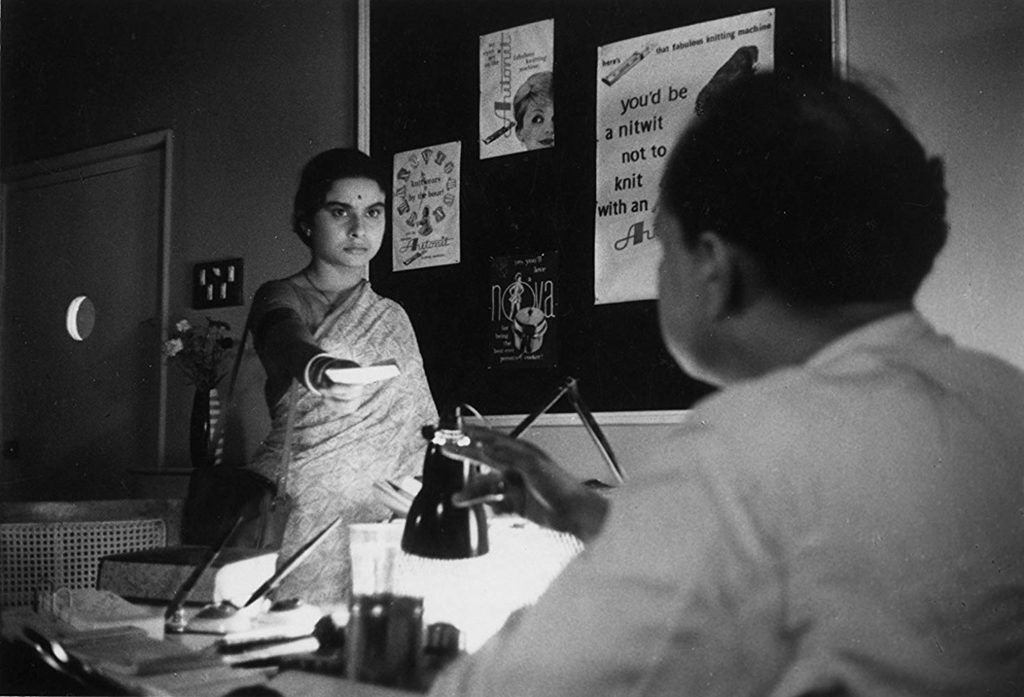

The Big City

1963, R.D.Banshal & Co., dir. Satyajit Ray

by Jonathan Leithold-Patt

The Big City/Mahanagar (1963) is a sensitively human-scaled portrait of modernity. The first of Satyajit Ray’s works to take place entirely in his native Calcutta and the first set in contemporary India, it depicts a shifting social landscape by focusing on a woman’s transition from housewife to breadwinning modern worker. Charting her newfound independence and the anxieties it engenders in her traditionalist working-class household, Ray registers the upheavals of patriarchal order caused by the influx of women into the labor force. Despite what its title might suggest, The Big City is not concerned with the sensorial spectacle or spatial transformations of the modernizing metropolis. More characteristic of Ray, it instead takes granular account of how individuals deal with the day-to-day realities of a changing world.

The Big City/Mahanagar (1963) is a sensitively human-scaled portrait of modernity. The first of Satyajit Ray’s works to take place entirely in his native Calcutta and the first set in contemporary India, it depicts a shifting social landscape by focusing on a woman’s transition from housewife to breadwinning modern worker. Charting her newfound independence and the anxieties it engenders in her traditionalist working-class household, Ray registers the upheavals of patriarchal order caused by the influx of women into the labor force. Despite what its title might suggest, The Big City is not concerned with the sensorial spectacle or spatial transformations of the modernizing metropolis. More characteristic of Ray, it instead takes granular account of how individuals deal with the day-to-day realities of a changing world.

The intimate perspective of The Big City is signaled from the opening shot, a close-up of a traveling railcar’s trolley pole. On board is Subrata (Anil Chatterjee), a bank clerk on his commute home. Ray quickly gets us acquainted with his family and the socioeconomic conditions that shape their domestic life. In the cramped confines of their apartment we meet Subrata’s father, Priyogopal (Haren Chatterjee); his mother, Sarojini (Sefalika Devi); younger sister Bani (Jaya Bhaduri); wife Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee); and son Pintu (Prosenjit Sarkar). The dynamic of the family, which Ray naturalistically captures through their routines, is strained by a shortage of money. Sarojini worries that their needs, including eyeglasses for the ailing Priyogopal, are burdening Subrata, whose meager income is barely enough to cover his daughter’s school tuition. Ray films these domestic scenes in medium shots that tend to frame multiple family members at once, emphasizing the limited space of their living quarters. Although the rooms are actually elaborate sets, they are grounded in a realism that feels authentic in its working-class detail.

Eventually, the financial hardships spur housewife Arati to get a sales job. Her husband initially objects, half-jokingly parroting sexist pieties about women belonging at home. He soon relents, however, leaving the real opposition to the rest of the family, whose disapproval verges on moral revulsion. In a remarkable shot, Ray tracks slowly in toward Priyogopal as he processes the news, his expression a simmering mixture of anger, bewilderment, and terror. “Salesgirl?”, he mutters, aghast. “My daughter-in-law?” Such dismay would lead one to think Arati was killed, not newly employed, but from the perspective of the culturally orthodox parents-in-law, a member of the family is being lost.

A profoundly empathetic artist, Ray sympathizes both with the family, whose traditionalist foundations are destabilized by changing social and economic realities, and with Arati, who embodies the liberated, autonomous working woman. And although Arati’s boss essentially stands in for callous capitalism at large, nobody in The Big City is flattened into a symbol of either virtue or evil. Ray understands how difficult it is for Subrata and his parents to reconcile Arati’s financial independence with their entrenched patriarchal attitudes, and portrays their anxieties accordingly. But he also delights in Arati’s empowerment, allowing us to share her excitement over earning a salary. Madhabi Mukherjee’s performance beautifully communicates her growing sense of pride, as in one exquisite scene where she holds the money from her first payment up to her face in the mirror, coyly smirking at herself with self-impressed glee. Mukherjee is equally adept at conveying Arati’s discontent as the indignities of her job, including her manager’s mistreatment of her Anglo-Indian coworker, increasingly challenge her value system.

The Big City gains its power from its nuanced performances and from Ray’s delicate, nonjudgmental view of the working class. He eschews polemics in favor of patient observation within a realist aesthetic. Befitting his gentle, inductive, and ultimately hopeful ethos, it is humans in The Big City who reveal the changes wrought by modernity, and it is humans who are given the power of deciding how to negotiate them.

*****

Satyajit Ray accepting his Honorary Oscar via satellite from his hospital bed during the 1992 Academy Awards ceremony. It was presented to him by Audrey Hepburn.