Godard Talks of Going Back to Zero in This Pair of Stark Transitional Works

Jean-Luc Godard, that dicey pickle of a filmmaker, was, back in the day, nothing if not prolific. Seventeen films in seven years, several of them medium-altering game-changers. Objectively, the volume of the output, and its impact, is nothing to scoff at.

Jean-Luc Godard, that dicey pickle of a filmmaker, was, back in the day, nothing if not prolific. Seventeen films in seven years, several of them medium-altering game-changers. Objectively, the volume of the output, and its impact, is nothing to scoff at.

That’s just about the point at which most anything can be objectively observed about the director’s filmography. Amorphous and intellectual, Godard has somehow bestowed a range of work that is at once uniquely challenging, experimental, confrontational, confounding, and outspoken. Insufferable? For many, that too.

It’s been said that you can’t truly know Godard’s work until you’ve, at some point, justifiably hated it.

It’s been said that you can’t truly know Godard’s work until you’ve, at some point, justifiably hated it. For most artists, that’s the other way around. But, hatred and alienation do not experts make. Even many of us who’ve been dancing with the iconoclast’s films for years, for decades, can still feel intimidated by them, particularly the stuff from roughly this point, the time of La chinoise and Le Gai Savoir, onward. Steeped entirely in the intensifying political strife of late 1960s France, these films are all to easy to ignore as irrelevant in a different time and place.

But is it right that the farther we get from his landmark debut Breathless (1960), the less we bother to value his work…?

*****

La chinoise

DIRECTED BY JEAN-LUC GODARD/1967

STREET DATE: OCTOBER 17, 2017/FRENCH/KINO CLASSICS

In the real-life ramp up to France’s nearly-revolutionary May of 1968, Godard saw trouble and discord brewing, there’s no debate. Always a political rascal, here he began his swing (descent?) into full Maoist exploration.

In the real-life ramp up to France’s nearly-revolutionary May of 1968, Godard saw trouble and discord brewing, there’s no debate. Always a political rascal, here he began his swing (descent?) into full Maoist exploration.

Unapologetically of its time and place, this unconventional screed’s cast of university aged would-be radicals couldn’t be more red, be it not for their glaring whiteness. The lot of five disenfranchised French youth (including Godard paramour Anna Wiazemsky, as well as Juliet Berto), led by the film’s only known star Jean-Pierre Léaud, go so far as to decorate their fine apartment with stacks and stacks of copies of Mao Tse-tung’s infamous “Little Red Book”, the published collection of essays and philosophies. The entire film, meaning the apartment where most of the film is set, heavily bears the vibrant and deliberate palate of the French flag, primary blue/white/red, the bright paint haphazardly applied wherever, and seemingly barely dry.

Unapologetically of its time and place, this unconventional screed’s cast of university aged would-be radicals couldn’t be more red, be it not for their glaring whiteness.

Students debate communist theory both with each other and interview style to the camera; they plot their demonstrations; and even engage a true-life former violent revolutionary for advise on violent protest. Will they or won’t they commit what very much sounds like terrorist actions? And what is the role of cinema in it all? In and around thought detours that seem to question the effectiveness and audacity of upper class students co-opting issues or which they lack firsthand knowledge of, these are the central questions of this experimental meta-narrative. And, for a film where very little happens, it’s not half bad.

Anne Wiazemsky, Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto in LA CHINOISE.

“Godard turns collage onto barrage”, film historian James Quandt informs us in his densely informative audio commentary track. It’s one of many keen and worthy observations found on Kino Classics’ recently released Blu-Ray of the film. Like many such observations, it’s own densities are worthy of and in keeping with its source material. In this particular case, the comment is directed towards Godard’s machine gun editing style of several experimental interstitials. Today’s filmgoers are most likely to perk up one such burst involving only three still images of comic book heroes, alternating quickly: Batman, Captain America, and Sergeant Rock. The symbolism of this moment – cartooned pop culture being fired at us repetitively and without stopping – is likely more relevant now than then.

Following La chinoise and just a few more films (a narrow window of time for the director at this point), Godard would cave to his own artistic progressivism and prophecies realized a year later with Weekend. For the next decade and onward following that brazen film – its closing proclamation nothing less than “the end of cinema” – traditional narrative, such as it’s ever been, isn’t just out the window in Godard’s cinema, it’s left burning in the street.

But for all of La chinoise’s progressive push into bold new filmmaking frontiers for Godard, it remains a part of his most-celebrated cluster of cinema output, albeit arguably the least celebrated title of the bunch.

*****

Le Gai Savoir

DIRECTED BY JEAN-LUC GODARD/1969

STREET DATE: OCTOBER 10, 2017/KINO CLASSICS

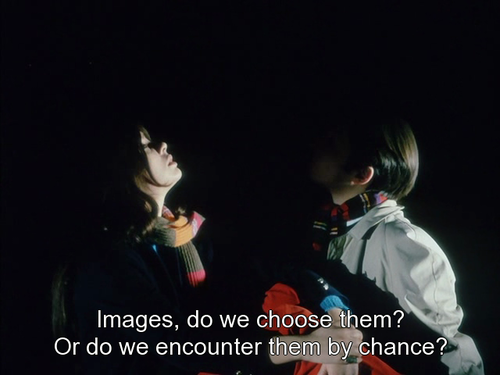

Just prior to France’s events of May of 1968, two young people, a man and a woman (Nouvelle Vague icon Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto), meet every night in a darkened television studio to hash out current events, the political climate, and how cinema might evolve to play the vital role they feel it’s destined to play. Questions are posited, ponderances are pondered, and lots and lots of still images go by on screen. (Would it be a 1960’s Godard film without at least one sequence of stills?)

Just prior to France’s events of May of 1968, two young people, a man and a woman (Nouvelle Vague icon Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto), meet every night in a darkened television studio to hash out current events, the political climate, and how cinema might evolve to play the vital role they feel it’s destined to play. Questions are posited, ponderances are pondered, and lots and lots of still images go by on screen. (Would it be a 1960’s Godard film without at least one sequence of stills?)

We must remember that Godard is someone who’s expressed his staunch love of cinema by rejecting cinema.

Nothing amorous goes on at these meetings, no romantic or sexual interludes of any kind. Some still images of Playboy-style pinups flashing by is as randy as this late ’60s French movie ever gets. These images are primarily visual commentaries on the commodification of sex, and the proliferation of alluring artifice in the face of national, even global tumult (particularly The Vietnam War, which is not overlooked.) That there meeting place is a darkened television studio, both alluding to the young generations comfort with and acceptance of the medium, as well as the medium’s apprehension toward televising any revolutions.

This is the work of an artist in transition, an artist incapable of not pushing everything about his work to the extreme. It is vibrant yet static, talky yet image-driven, philosophical yet disposable. All of this is by radical design. We must remember that Godard is someone who’s expressed his staunch love of cinema by rejecting cinema. Le Gai Savoir (Translated, “The Joy of Learning”) is his navigating of those crossroads.

If one has never seen a Godard movie before, Le Gai Savoir has to be among the worst places to begin. (For that, consider going to Breathless, A Band of Outsiders, or even Contempt – all more traditional, if only by comparison to the film being reviewed.) In his published essay included with the Blu-Ray, punk rock icon turned film critic and writer Richard Hell admits that Le Gai Savoir plays more like a classroom exploration than a movie – even as he lauds its unique nature and bold approach. It’s a political exercise that’s televisual in origin (it’s true, French television courted Godard to create a program, and he dropped this on them), talky talky as ever, and yet, Hell knows the joy of The Joy of Learning.

*****

Fresh off of a theatrical revival by Kino Lorber, these Blu-Rays of recent Gaumont restorations of these films looks and sound remarkable. Excellent bonus features and booklet essays seal the deal for adventurous film buffs, Godard devotees, and those interested in revolution from a fifty-years-on French perspective that’s unfortunately more timely today than it ever ought to be, these are fine, if curious, additions to any shelf of World Cinema.

The images in this review are not representative of the actual Blu-rays image quality and are included only to represent the films themselves.