Wilder In Wilder Times

DIRECTED BY BILLY WILDER/1972

STREET DATE: OCTOBER 10, 2017/KINO LORBER STUDIO CLASSICS

Looking back at a filmography spanning 5 decades, 27 directed films, and well over 50 scripts, the Jazz Age to Post-modern sweep encompassing the German silent film People on Sunday (1930) on one end and the Hollywood black comedy Buddy Buddy (1981) on the other inevitably invites reflection on the defining factor of Billy Wilder’s unique placement as writer-director par excellence of Hollywood’s Golden Age. From his writing collaborations with Charles Brackett, most notably scripts for sparkling romantic comedies like Midnight and Ninotchka (both 1939), through directorial masterpieces like Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the primacy of the written word and the finely-textured, brittle dimensions of character – and characters – in conflict is readily summed up by the high style and witty substance of his lengthy, transcontinental, multilingual writing-directing career. Highly-refined and seemingly made-to-order, a Billy Wilder film exudes wit and character with effortless ease.

Looking back at a filmography spanning 5 decades, 27 directed films, and well over 50 scripts, the Jazz Age to Post-modern sweep encompassing the German silent film People on Sunday (1930) on one end and the Hollywood black comedy Buddy Buddy (1981) on the other inevitably invites reflection on the defining factor of Billy Wilder’s unique placement as writer-director par excellence of Hollywood’s Golden Age. From his writing collaborations with Charles Brackett, most notably scripts for sparkling romantic comedies like Midnight and Ninotchka (both 1939), through directorial masterpieces like Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the primacy of the written word and the finely-textured, brittle dimensions of character – and characters – in conflict is readily summed up by the high style and witty substance of his lengthy, transcontinental, multilingual writing-directing career. Highly-refined and seemingly made-to-order, a Billy Wilder film exudes wit and character with effortless ease.

With 1957’s Love in the Afternoon, the Austria-born Wilder began a collaboration with fellow emigre I.A.L. Diamond, who hailed from Romania, and the two writers for whom English was a second language quickly produced some of late Classic Hollywood’s cleverest and best-written scripts. Coinciding with the director’s most fertile period, 1959 saw the release of the cross-dressing farce Some Like It Hot, immediately followed by the romantic tragicomedy The Apartment (1960); crowning this literal one-two-three punch with the Cold War satire One Two Three (1961).

On the cusp of the staid and conformist ’50s, and anticipating the cultural and sexual revolutions of the ’60s, Wilder’s keenly cynical yet warmly humanistic sensibility resonated strongly with movie audiences eager to see Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in drag, the afterhours goings-on off Madison Avenue, and shenanigans across what was then the most contentious border on earth: the literal divide between East and West in the city of Berlin. Dressing down a couple of male chauvinists, stripping diplomatic dignitaries of their last shred of dignity, along with frankly detailing the unsavory vagaries of the American workplace, Wilder at his era’s best remain vivid black-and-white and frenetic widescreen reminders of their boop-boop-ee-doo and ring-a-ding-ding times, sex-wise and politics-wise. The push-and-pull between boundaries of good taste and bad found their most potent expression in Wilder’s admirable lack of restraint, especially where convention and standards of propriety were at its most prudish.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

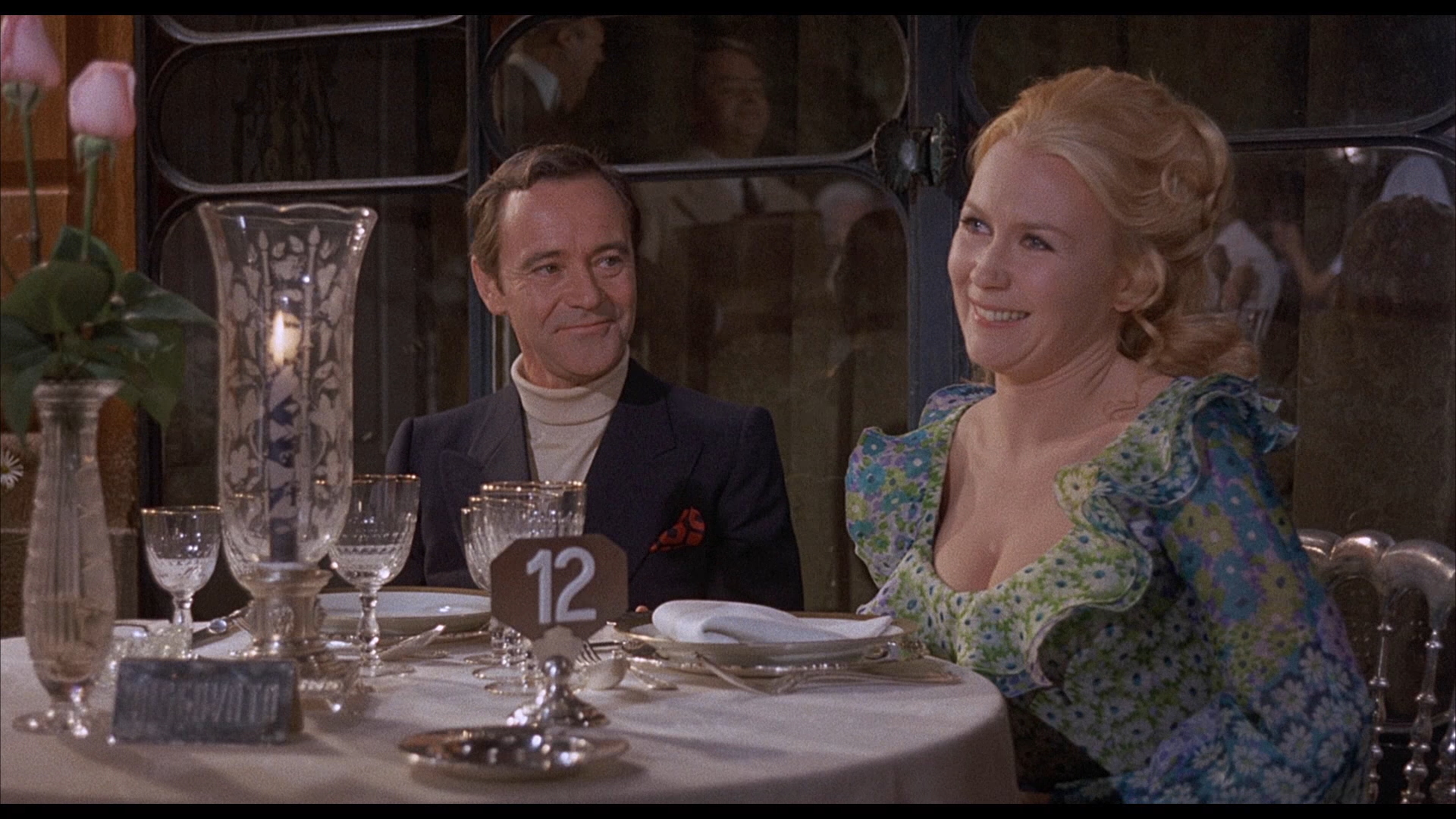

Wilder times lay ahead, however, and subsequent Wilder-Diamond films suffered from a culture that was quickly catching up. Avanti!, appearing in full 1972 color, makes joking reference to Henry Kissinger, Billy Graham, and Ralph Nader, yet somehow seems mired in an era of Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Khrushchev. Wendell Ambruster, Jr. (Jack Lemmon) arrives on the island of Ischia in Naples to claim his father Wendell Ambruster, Sr.’s body, who died in a car accident with a fellow guest from the island’s Grand Hotel Excelsior, where he spent his long-term annual summer retreats.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

The fellow guest, as it turns out, was Sr.’s unknown, equally long-term mistress Katharine Piggott, a British manicurist whose daughter Pamela (Juliet Mills), a young Londoner, has also arrived at the hotel to claim her mother’s body. Expertly handling the complicated postmortem export visas, not to mention the three-hour mid-afternoon Italian lunch, is the hotel’s head manager Carlo Carlucci (Clive Revill), who is as efficient at dealing with bureaucracy, blackmail, and body-snatching as he is tolerant of human frailty in general and encouraging of romantic intrigue in particular.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

Part romantic comedy, part travelogue, and part door-slamming farce, Avanti! shares the witty hallmarks of Wilder’s previous body of work, along with hints of the darker and more melancholy aspects of romance explored to its fullest extent in his previous The Apartment. Based on a failed Broadway play by Samuel Taylor, whose earlier play Sabrina Fair (1953) provided the basis for his 1954 film Sabrina, the film disguises its play origins well with lots of pretty oceanside scenery, but at 2 hours and 24 minutes feels at least 24 minutes too long.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

It does, however, have wonderful performances, with Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills winsomely winning in their respective romantic roles, and Clive Revill practically stealing every scene he’s in with a professional comic efficiency precisely equal to the efficient professionalism of his character. The main problem is that Wilder strains for effect here, and when even laying his two romantic leads naked on a rock, in the full morning glare of the Italian sun, fails to shock or delight, possibly the restraints he effortlessly transgressed in the past are simply no longer there.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

As such, the film rather reminded this reviewer of another effort from an established director earlier in 1972. Like Wilder in Avanti!, Alfred Hitchcock’s vision may have been best served when he could tantalizingly suggest subjects that standards of the day might not have allowed to him to explicitly show – as in 1960’s Psycho – as opposed to the onscreen death of suggestive subtlety with which the Master of Suspense full-screen staged a strangulation/rape murder in that same year’s Frenzy. Not to rob either auteur of their individual skills of storytelling, even in a filmmaking era with which the directors might not have felt entirely comfortable, but that both scenes invite more discomfort than appreciation for this viewer may suggest that even the greatest storytellers can be flummoxed by being ever-so-slightly out-of-tune with their times. And further not to conflate or compare serial rape murdering with a little innocent outdoor exhibitionism, but bad taste without the wit to redeem it was undoubtedly a cardinal sin for both veteran directors.

photo credit: DVD Beaver

Overall, though, Avanti! is pleasant and leisurely, and like Lemmon’s Ambruster’s initial irritation with Mills’ Piggot’s free-spirited and romantic ways may overcome a viewer’s resistance on subsequent viewings. Kino Lorber’s first-time release of Wilder’s later career effort on Blu-ray does virtually pop off the screen in a visual manner best befitting the film’s beautiful location photography, and enthusiastic interviews with cast members Juliet Mills and Clive Revill accompanying the disc made me want to go back and re-view the scenes that clanged and thudded on my initial viewing. Possibly being unaware of Wilder’s previous body of work may actually improve a viewer’s individual reaction to the film, but Avanti! still has enough wit, style, and substance for appearing in even wilder times.