26 That’s Right 26 Selections Of The Greatest Circus Movies On Earth!

Part II: Oddity

Continuing my grandfather Dean Mory’s circus saga, his tumbling, hand-balancing, and high-flying apprenticeship with retired circus showman Bill Schulz in Manitowoc, Wisconsin may have given Grandpa a performing nickname of “Don Moray”, just as Schulz’s stage name of “Billy Lester” gave its name to the unique, community-local circus school, but as subsequent talcum-powdered, parallel bar-gripping, vault-leaping events transpired, Grandpa’s actual performances were confined to isolated, limited engagements over the next few decades:

During the early years of the Depression, as a student athlete and phy. ed.-major at UW-Madison, “Don Moray” semi-occasionally headlined a few summer-break shows between dish-washing and assistant coaching gigs on the Orpheum Theatre vaudeville circuit. He developed a 10-minute routine involving a special table with a hole in its center, onto which he bodily propped his 150-pound frame – upside-down and one-armed – through the fragile-appearing agency of a thin, white cane.

As the second World War loomed, Grandpa – by this point a UW-Madison instructor and assistant gymnastics coach – occasionally made the fourth man to a three-man hand-balancing team featuring Bill Schulz, Jr.; the talented acrobatic son of Grandpa’s circus mentor, Bill Schulz. Transposing gravity-defying body pyramid-configurations from the Lake Michigan beaches of Manitowoc to various Midwest-tour engagements of the USO, “Don Moray” provided, according to the need of the routine, either a powerful professorial pull up to the top or a base of solid civilian support from below.

In the early ’50s, “Don Moray” made his final summer appearances in rural Madison, WI-area town fairs and carnivals. Between livestock shows, ballgames, and bull rides, Grandpa dutifully trotted out the old table-and-cane act to the slack-jawed amazement of the local yokels, but ultimately found the remuneration unequal to the effort. He retired the name (and act) after a comically frustrating incident with two angry oxen and a hungry goat. (He didn’t elaborate further.)

As student wrestler and gymnast, athletic director for the YMCA, and later head gymnastics coach and assistant professor at UW-Madison, Grandpa’s professional career left little time for performance, but his performing instincts found natural expression even as the small, now-balding man entered his fourth decade – unusually quiet and low-key for all his (often hidden) talents – and with his wife of 15 years and two boys settled into a small, white house with a very big yard in suburban Monona, WI:

During the summers, Grandpa often picked up a little cash moonlighting as a lifeguard in the wealthy Madison suburb of Maple Bluff. When calling out the legal “everybody out!” pool-breaks every two hours, Grandpa became known for entertaining the momentarily inconvenienced swimmers by performing back-flipping, body-twisting high-dives during the ten minutes of empty pool time.

Teaching his classes near his corner office in UW-Madison’s historic Red Gymnasium, Grandpa also came to be known for leading entire classes on “injury-free vigilance”… often while hanging from the top of a rope, balancing on a ladder, or swinging on a trapeze. In honor of one of his heroes, silent movie star Harold Lloyd, Grandpa was sometimes referred to as the UW’s “Safety Last Professor”.

Rather than writing up a simple proposal, Grandpa once “demonstrated” for University officials the cramped spatial conditions of one of his team’s gymnastics venues by repeatedly (and purposely) banging his feet, back, elbows, and head against its ceiling on the trampoline and high parallel bars. The Phy. Ed. Department received a grant to structurally raise the roof of the gymnasium the next semester.

As these random anecdotes from my grandfather’s abbreviated performing and non-performing middle years might show, the circus as such was somewhat removed from his day-to-day experiences, but there was always an element of the circus in how he went about his work and daily tasks. And regarding the lake-locked, apple and walnut tree-lined community of Monona – about as white-bread “American” a town as one might have seen on TV at the time on Leave it to Beaver – Grandpa crowned that anxious yet uneventful decade of bland normality with as “circus” a gesture as his home-improvement ambitions could mischievously muster: digging about 30 feet under a newly-constructed garage, the Morys’ became possibly the first suburban residence in the state to house a full-size, fully-functioning gymnasium under its structure.

So before we resume Grandpa Dean’s continuing circus saga in our third installment, as he entered his eventful retirement years, I’d like to pause on the image of a little white house on a well-paved street with a lot of other little white houses, but with the crucial difference being that this particular household concealed beneath its unassuming surface 30-feet-high white ropes, parallel bars, swinging ladders, mounted rings, balancing globes, unicycles, all manner of juggling equipment, a taut length-stretched tight-rope, two high-flying trapeze rigs, and a cable-reinforced trampoline. Yes, the genuine, marvelous oddity of my grandfather’s middle years is that while many of his neighbors may have been excavating bomb shelters or shoveling out end-of-the-world bunkers, Grandpa instead offered the uneasily quiet neighborhood an underground, 3-ring circus.

…

“Oddity” is the second theme of our continuing circus movie marathon, with today’s selections offering an unusual panoply of marvels, emotions, and even physical attributes well beyond the pale of day-to-day life. From failing traveling caravans and fairground spectacles to off-road sideshows and animal menageries, the natural world of reason is circus-countered with an often unnatural world of transcending (and even transcendent) possibility. Quoting the great W.C. Fields, a circus barker if there ever was one, “It baffles science!”

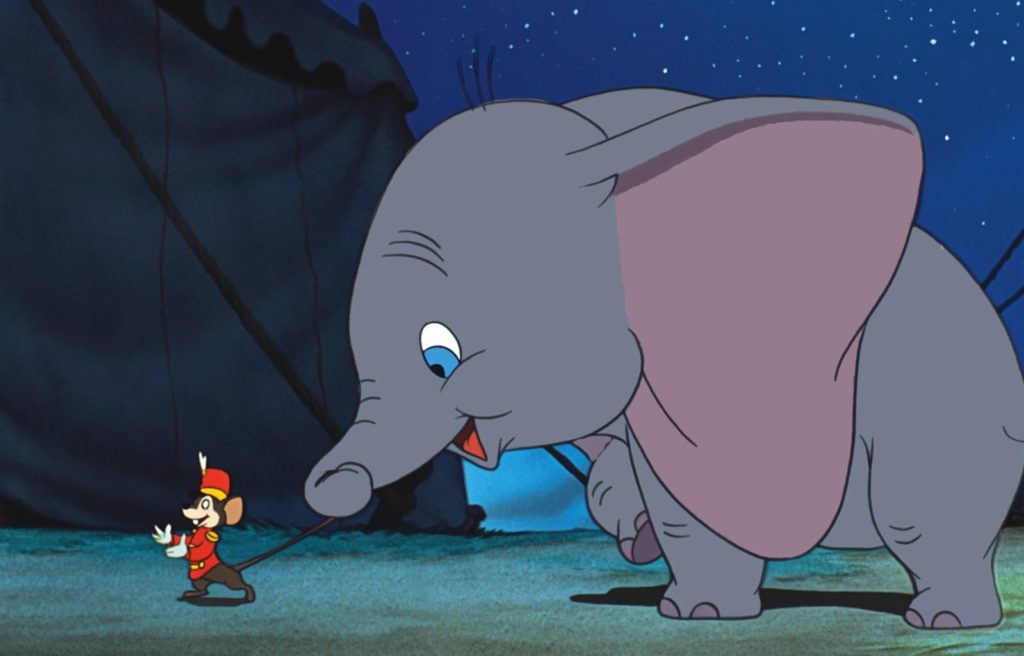

Dumbo

1941, Disney, dir. Ben Sharpsteen

Combining sideshow oddity, outsize performance, and animal kingdom spectacle in 64 minutes of pure animated glory, Walt Disney’s great tale of circus life came courtesy of the titular “little elephant with the big ears”. From my very first viewing as a 4- or 5-year-old, in which I assumed that Jumbo Junior’s big sneeze “reveal” of his equally big ears actually “blew out” said features to head-disproportionate size, I can’t think of any movie that more shaped my childhood understanding of the circus and its denizens beyond even the colorful circus posters that decorated my bedroom or circus tales first-hand delivered by my performing grandpa. Indeed, Dumbo occupied the same drawn-motion space in my imagination as those indelible images and stories, and as fortunate as I was to have a relative to lead me through its cotton-candied corridors, Dumbo himself was equally fortunate to have a steadfast circus companion in one film-length unnamed (until revealed by a signed talent at film’s end) Timothy Q. Mouse. My single favorite relationship in a Disney animated film, Dumbo grasping the little mouse’s tail as both wend their weary way across the circus midway is for me one of the most moving images in all film. Mr. Stork’s kazoo-tuned delivery of the Happy Birthday! Song; a five elephant-high “pyramid of pulchritudinous pachyderms”, balancing precariously atop a balancing globe; the near-avant garde, surrealist sequence of drunken, hallucinatory Pink Elephants; the flying elephant’s flap-eared reveal through a hazy cloud and a murder of racially-questionable-though-infectiously-scatting Jim Crows; Dumbo remains a definitive movie statement on the Golden Age extremities of the Great American Circus.

The Chimp

1932, Hal Roach/MGM, dir. James Parrott

“Red lighting” was showbiz lingo for being stranded by the circus, and that’s just what happens to poor pantomime horse and human cannon ball performers Laurel & Hardy after the struggling Finlayson Circus (named, presumably, for balding, mustachioed L&H antagonist James Finlayson; who appears as the circus Ringmaster) goes belly-up. Left a flea menagerie and – despite the title – a flower hat-wearing gorilla named Ethel (simian-suited Hollywood legend Charles Gemora) by the circus tent-folding non-profit plan, Stan and Ollie take their troublesome mini-zoo to a nearby boarding house, where they innocently intrude on a domestic situation involving the jealous landlord (Billy Gilbert) and his roving wife, also named Ethel (Dorothy Granger). In three reels of comic though leisurely-paced insanity, these bare ingredients receive their most ridiculous iteration possible, as the predictable results of mistaken identity, gorilla affection, and fleas loose on a double-bed are lingered lovingly over with the shrieks, arguments, and slapstick nonsense that classic comedy’s clueless clowns elevated to the level of screen poetry. With the movie curtain closing on the vaguely apocalyptic image of an angry female gorilla dressed in a tutu and armed with a pistol, shooting up the furnished rental with a fury to match the rising billow of gunpowder smoke, The Chimp essentially brings circus anarchy out of the Big Top and instead wreaks glorious havoc on the Rube world. If I had to imagine a sequel to these goings-on, I suppose Ethel the gorilla must have had no recourse but to climb the tallest structure in town – possibly a church tower or city hall – while Stan and Ollie senselessly blubbered and frantically shouted, respectively, below.

Variety

1925, UFA, dir. E.A. Dupont

A sackcloth-suited convict – # 28 – is called into the sparsely appointed offices of the imposingly white-bearded warden, a key-lit crucifix looming luminously over his desk, to discuss secrets, shame, and salvation; the tale of jealousy, betrayal, and violent rage that unfolds in flashback over the next 9 ½ reels possibly the progenitor of all tragic 3-ring, tri-cornered romantic melodramas. Trapeze artist and carnival proprietor Boss Huller (the broodingly brilliant Emil Jannings) leaves his wife and child for the beguiling waif Bertha (Lya De Putti), eventually forming an uneasy three-way partnership on the swinging bars with the romantically scheming, roving-eyed Artinelli (Warwick Ward); filling the Berlin Wintergarden to capacity even as the nightly performance without a safety net threatens to spell doom – and ultimately romantic tragedy – for the high-flying trio. Stunningly shot by Karl Freund (The Last Laugh [1924]) and Carl Hoffman (Dr. Mabuse [1922]), director E. A. Dupont’s visual masterpiece – one of the crowning achievements of the Weimar Era of German filmmaking – features swift-swinging camera shots and vertiginous focal lengths across the 50-foot-high space of the flying trapeze. As the first unofficial selection in our equally unofficial sub-section of circus movie silents, Variety offers a purely image-driven view of the Big Top, with the emotional toll of death-defying leaps, thrills, catches, and near-misses visited three-fold upon its resin-grasping, heart-gripped participants.

The Man Who Laughs

1928, Universal, dir. Paul Leni

By the late ’20s, many of the grand luminaries of 1920s German Cinema – including Nosferatu (1922) director F.W. Murnau and Variety star Emil Jannings – had been lured by the seductive powers of the Hollywood studio system, with many of those so drawn exerting their own seductive powers on the shape and substance of Hollywood studio fare during that heady, art-influential period. Two other such luminaries were Waxworks (1924) director Paul Leni and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) star Conrad Veidt, and under the auspices of Universal studio chief Carl Laemmle, looking to duplicate the success of the studio’s two previous “super productions” of 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera, spared no expense or artistic restraint in lavishly and imaginatively adapting Victor Hugo’s 1869 English historical novel and epic tale of Grand Gothic Romance to the big screen. The hideously rigor mortis-grinning clown Gwynplaine (Veidt) IS the title’s laughing man, and in this British Restoration-era saga, the facially-disfigured traveling sideshow performer — secretly heir to a peer’s title and a seat on the House of Lords – is supported through his travails by an alchemist and a blind admirer (Cesare Gravina and Mary Philbin) while surrounded by rapacious aristocrats (Brandon Hurst, Olga Baklanova) and the entire mocking court of the reigning English monarch herself (Josephine Crowell as Queen Anne). Unseen for decades, before being rediscovered, restored, and re-released on home video in the mid-00s, The Man Who Laughs is possibly best known for Universal Studio legend Jack Pierce’s make-up design of the ghastly-grinning clown, which proved influential not only for later studio monstrosities like Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), and The Wolfman (1941), but also directly inspired the equally ghastly grin of Batman comics villain The Joker.

He Who Gets Slapped

1924, MGM, dir. Victor Seastrom (Sjöström)

As may have been apparent to movie fans from both the discussion of makeup AND the description of a physically disfigured protagonist above, the role of Gwynplaine in Universal’s The Man Who Laughs had been originally intended for Hunchback and Phantom star Lon Chaney. Even silent film’s Man of a Thousand Faces couldn’t play them all, however, but he did spend the 1920s convincing audiences that he somehow could. With MGM’s 1924 film He Who Gets Slapped, the then nascent studio’s first commercial release, Lon Chaney set a pattern for the rest of his career wherein he portrayed a performer seeking both revenge and (ultimately unrequited) romance within the story and psychological demands of the Gothic-tinged melodrama. Unsurprisingly, many of these sagas of suffering are set under the all emotions-canvassing tent folds of the Big Top, and this heart-rending 3-ring tale of a romantically-wronged and reputation-ruined clown – masochistically performing under the name and self-explanatory act of HE Who Gets Slapped – wrings every last ounce of tragedy out of each flush of anguish momentarily flashing across Chaney’s otherwise laughing face. Important to the developing careers of Norma Shearer and John Gilbert, future MGM stars here playing second-lead lovers, and its director, Swedish master Victor Sjostorm, here earning his first film success stateside, it ultimately seems appropriate even beyond its star’s later success that a movie empire should have been here built upon the logo of a roaring lion, with a beautifully rendered climactic scene of a villain being ripped apart by possibly the same lion who provided that logo’s famed roar!

The Unholy Three

1925, MGM, dir. Tod Browning

Continuing our circus oddity-themed dip into silent movies, and further continuing our Lon Chaney celebration within that silent circus movie theme, inevitably brings us to the key silent, circus, and oddity-themed partnership between Chaney and film director Tod Browning. A one-time clown and performer who had literally run away with the circus as a child, Tod Browning came to films in the mid-teens – around the same time as stage performer Lon Chaney – and began working as an actor in two-reel comedies, gradually transitioning from a comic actor to a dramatic film director by the end of the 19-teens. Naturally attracted to subjects with a hint of the macabre, along with any suggestion of physical transformation or deformity, Browning found a more than willing collaborator in the actor who had already brought such extreme characterizations to the big screen as a con man contortionist (1919’s The Miracle Man), an amputee gangster (1920’s The Penalty), and the silver screen’s most famous bell-ringing hunchback (1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame). In their second screen collaboration, Chaney’s role of a ventriloquist and old lady-disguised pet shop owner who forms a three-man robbery gang of former sideshow performers – including himself, a midget (Harry Earles), and a strongman (Victor McLaglen) – must have seemed rather par for the course. As Professor Echo, voice-throwing and granny cross-dressing trick artist and outlaw, Chaney the screen performer is expertly guided by Browning’s singularly compassionate though undeniably bizarre vision towards both humanizing his misguided character and lending affect to the otherwise pedestrian genre paces of the crime melodrama. The Unholy Three may groan and creak around its antique edges, but its oddity and extremity, courtesy of the emotional depths imbued by its star and director, never overshadow its essential humanity.

The Unknown

1927, MGM, dir. Tod Browning

At a lean five reels (most prints projected at the silent rate of 18 frames/second run around 50 minutes), director Browning and star Lon Chaney’s fifth film packs more marvels, melodrama, and general weirdness into its short running time than films twice its length. Chaney is Alonzo the Armless, a knife-throwing sideshow performer who, per his suggestive stage name, hurls dangerously edge-sharpened steel nightly at his beloved Nanon (Joan Crawford in her breakout film role), perilously pinned to a “wheel of death”, without the use of his arms. Moreso than any Browning film to this point, The Unknown deals unequivocally with the outrageous and reality-transgressing aspect of the circus, and in this tale of deception and trickery – and, more pointedly, physical and emotional mutilation – the performers who daily bring curiosity-seekers to question their own conception of “humanity” are forefront and center in a way their “side” status of showmanship rarely allows. Without giving too much away, as this is a film that reel-to-reel thrives on the visual surprise of, say, the reveal of a body harness, or a hand with two opposable thumbs, the film’s final sequence of a scantily-clad Nanon on a raised platform, wildly whipping two white steeds running in opposite directions, while harness-held by a strongman (Norman Kerry) perilously in between, is among the most shocking in all silent film. As any sideshow audience may have attested when venturing off-midway, The Unknown aspects of what one has just witnessed may elude cogent expression, but it was undeniably worth the two bits.

Laugh, Clown, Laugh

1928, MGM, dir. Herbert Brenon

One of Lon Chaney’s final silent films is, happily, one of his very best, and this romantic circus melodrama by way of a 1923 David Belasco stage production – which itself seems to have been inspired by the 1892 opera Pagliacci – offered the Protean actor the fullest range of dramatic expression that the pure eloquence of silent cinema could afford. As Tito the great clown, who performs with his partner Simon (Bernard Siegel) under the popular two-clown act of “Flik and Flok”, Italy’s national circus treasure harbors a secret, self-destructive passion for his adopted daughter Simonetta (Loretta Young, in her first adult-starring movie role), who herself is receiving romantic attention from the kindly, handsome young aristocrat Count Ravelli (Nils Asther). The tragic clown is of course nothing new in storytelling – and in fact Chaney had already essentially played the role four years earlier in the previously covered He Who Gets Slapped – but the thematic development of Chaney’s many roles as outsiders, outcasts, and outlaws somehow found its natural home under the Big Top, where outsize emotion and unrequited longing is rather achingly profound under two layers of grease-paint and behind a heart-breaking grin. As Tito speeds headlong, upside-down, and 30 feet up on a highwire towards self-driven doom, the sudden gasp of the circus audience’s bated breath may not be captured by the art form’s absent soundtrack, but we the movie audience undoubtedly still hear those raucous sounds of laughter turn to piercing shrieks of horror.

Freaks

1932, MGM, dir. Tod Browning

Two years after the untimely death of Lon Chaney, director Tod Browning returned to the studio under whose aegis had produced their greatest screen collaborations. At MGM, de facto studio chief Irving G. Thalberg hoped to counter the success of the fantasy-horror tales that competing studio Universal had recently unleashed with Browning’s more realistic screen vision. Envisioning more a tale of real-life terror than the dark poetic fantasy of Universal’s Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (also 1931) director Browning realized those ambitions with a sympathetic shocker that similarly tested the boundaries of what was both known and unknown, but with an assemblage of real-life performers whose “horror” was a creation of the natural world rather than those created unnaturally by science. With Freaks, the long-vanished circus sideshow is film documented for all time – the “half boy” Johnny Eck, the “Siamese twins” Daisy and Violet Hilton, the “living torso” Prince Ramdian; along with the various microcephalics who gave the term “Pinhead” to the language – even as the rapid medical advances of the first third of the twentieth century would quickly see the physical defects and deformities of these off-midway denizens virtually vanish from the world. The romantic melodrama that drives the film’s plot, where a small performer (Harry Earles) is manipulated by a “beautiful” trapeze artist (Olga Baclanova) and her covert strongman lover (Henry Victor), essentially takes a backseat to the brilliant day-to-day “view” Browning captures of, say, a woman without arms performing household tasks, the romantic entanglements (that we are only left to imagine) of the conjoined twins, or simply (and most astonishingly) a man without arms or legs lighting and enjoying a cigarette. Browning, who had previously depended on a great performer for these spectacular screen effects, but who nonetheless was still pretending to perform without arms or legs, here squarely offered audiences the real deal, in which his sensitive portrayal of human oddity made villains out of “attractive” people and heroes out of the titular Freaks. As a film, Freaks may have proved too strong for contemporary audiences, but in its stark depiction of the odds real people heroically overcame in order to merely physically function in the world continues to resonate to this day.

Part III: Spectacle

UP NEXT ON THE 3-RING MARATHON!