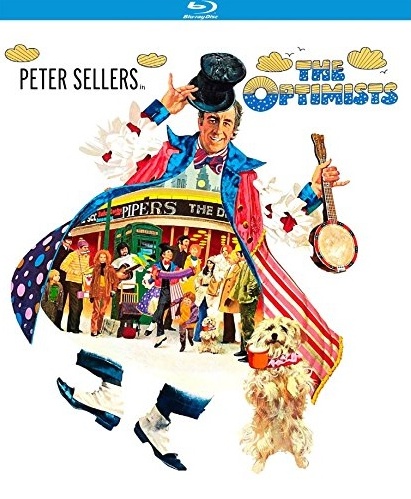

Peter Sellers Evokes Dickens, Accidentally Invents Mumblecore

DIRECTED BY: ANTHONY SIMMONS/1973

STREET DATE: APRIL 25, 2017/KINO LORBER

Folded messily amongst the movies we first think of starring Peter Sellers are movies like this, forgotten off-roads that the eye flits over on the IMDb list. Some are understandably so… one-off cameos, broad, poorly-written or too-’60s-soaked satires, or simply odd titles not met at the time with favor by American audiences. The Optimists makes its reasons for obscurity known in the first moments, as it fills up with flat, maudlin music (by Sir George Martin!) over sleepy images and slow-moving character building. But it’s got a sneaky charm, the kind of movie someone surprises you with by calling it their favorite childhood go-to. And once you’ve slouched into that “go with it like a kid would” mode, the movie subtly captivates.

Folded messily amongst the movies we first think of starring Peter Sellers are movies like this, forgotten off-roads that the eye flits over on the IMDb list. Some are understandably so… one-off cameos, broad, poorly-written or too-’60s-soaked satires, or simply odd titles not met at the time with favor by American audiences. The Optimists makes its reasons for obscurity known in the first moments, as it fills up with flat, maudlin music (by Sir George Martin!) over sleepy images and slow-moving character building. But it’s got a sneaky charm, the kind of movie someone surprises you with by calling it their favorite childhood go-to. And once you’ve slouched into that “go with it like a kid would” mode, the movie subtly captivates.

Sellers is big-nosed hobo, Sam – see, it’s lost you already – who lives in the squalor of a near-abandoned brick tenement next to a soupy city dump, occasionally wandering into London with his baby-pram full of props and wigs and his dirty mop of a dog, Bella – a sharp performer in her own right – to ply some sidewalk vaudeville for a few pence. There he hits like a carome against the anonymous consumer class in a wistfully out-of-step flow of small tunes, limericks, and street-wise philosophical bromides (“you can’t eat soap and wash your face with it”), and not exclusively, but often, speaks in voice-over rhymes, non sequiturs, and indistinct mumbles that could rival a bemused Popeye. Writer-director Anthony Simmons pulls you down into the melancholy degradation of the want-to-be-forgotten lower class, while never dipping so deep into grime that hope is completely lost. Into his photorealistic world of detritus and piles of wet garbage, Simmons drops a couple of cute but savvy kids, a brother and sister (played by John Chaffey and Donna Mullane), to test the depth of Sam’s curmudgeonhood. Even with tykes about, Sellers isn’t afraid to play Sam with real insufferable bitterness – not for sit-com laughs, but for revelation. He’s a real ogre living in a dank, forgotten cave when these two sibling hobbits from a nearly-broken home dare to approach and befriend him. From there the story is a roll-out of shuffled vignettes describing their growing trust for one another.

Writer-director Anthony Simmons pulls you down into the melancholy degradation of the want-to-be-forgotten lower class, while never dipping so deep into grime that hope is completely lost. Into his photorealistic world of detritus and piles of wet garbage, Simmons drops a couple of cute but savvy kids, a brother and sister (played by John Chaffey and Donna Mullane), to test the depth of Sam’s curmudgeonhood. Even with tykes about, Sellers isn’t afraid to play Sam with real insufferable bitterness – not for sit-com laughs, but for revelation. He’s a real ogre living in a dank, forgotten cave when these two sibling hobbits from a nearly-broken home dare to approach and befriend him. From there the story is a roll-out of shuffled vignettes describing their growing trust for one another. It’s a kind of Hansel and Gretel meets urban decay commentary, but instead of eating them alive, their own flesh-and-blood reality inspires Sam’s first true smile in twenty years, his ashen vagrant face brightening soon as he slowly cedes to quasi-responsibility for the children’s entertainment and education. In the film’s best long sequence, Sam takes the kids to rescue a dog of their own from the pound – until he finds out it’ll cost him three pounds fifty he doesn’t have. When their father, wielding loudly an impatient bluster that grows right out of the daily struggle for a plug quid, yells them away with a loveless denial of anything like an allowance, Sam intercedes by paying them to watch his dog, to earn money for their own. It’s surrogate life-lessons from the lowest common denominator.

It’s a kind of Hansel and Gretel meets urban decay commentary, but instead of eating them alive, their own flesh-and-blood reality inspires Sam’s first true smile in twenty years, his ashen vagrant face brightening soon as he slowly cedes to quasi-responsibility for the children’s entertainment and education. In the film’s best long sequence, Sam takes the kids to rescue a dog of their own from the pound – until he finds out it’ll cost him three pounds fifty he doesn’t have. When their father, wielding loudly an impatient bluster that grows right out of the daily struggle for a plug quid, yells them away with a loveless denial of anything like an allowance, Sam intercedes by paying them to watch his dog, to earn money for their own. It’s surrogate life-lessons from the lowest common denominator. The running theme of dogs as currency for happiness is strong throughout the movie. Sam, who openly believes in the faithfulness of dogs over the chicanery of other people (“a dog will always be your friend”), has essentially replaced his wife with Bella; the kids work against all reason to earn enough to have one of their own, expecting untold joy in the transaction; and the children’s father loudly protests against the price it costs to have such a luxury. Dogs are central to the story, their lowliness mirroring the place children and vagrants occupy in a world that would throw them into the same part of town as their trash. But this isn’t the apotheosis of the forgotten – Sam and the kids are drawn as rounded humans, with bristling anger and suffocating pride. More so than a story about finding diamonds among the forgotten, it’s about the forgotten finding much to value in themselves.

The running theme of dogs as currency for happiness is strong throughout the movie. Sam, who openly believes in the faithfulness of dogs over the chicanery of other people (“a dog will always be your friend”), has essentially replaced his wife with Bella; the kids work against all reason to earn enough to have one of their own, expecting untold joy in the transaction; and the children’s father loudly protests against the price it costs to have such a luxury. Dogs are central to the story, their lowliness mirroring the place children and vagrants occupy in a world that would throw them into the same part of town as their trash. But this isn’t the apotheosis of the forgotten – Sam and the kids are drawn as rounded humans, with bristling anger and suffocating pride. More so than a story about finding diamonds among the forgotten, it’s about the forgotten finding much to value in themselves.

The images in this review are not representative of the actual Blu-ray’s image quality, and are included only to represent the film itself.