A Double-Fisted B-Movie Double Bill

(SUNSET IN THE WEST) DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WITNEY/1950

(THE SCAR) DIRECTED BY STEVE SEKELY/1948

STREET DATE(S): April 18, 2017/KINO LORBER

“Now people are going to say to you, Wallace Beery, wrestling, it’s a B-picture. You tell them: BULLSHIT! We do NOT make B-pictures here at Capitol. Let’s put a stop to that rumor RIGHT now!”

– Capitol Pictures producer Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner); Joel & Ethan Coen’s Barton Fink (1991)

Kino Lorber has given me an opportunity this late April to highlight an economy of story-telling, running-time, and production cost with a makeshift tribute to the preferred form of low-budget movie-viewing: the double bill. Though separately packaged, a pair of roughly contemporary genre favorites receive simultaneous release on Blu-ray home video; recalling in a possibly not-so-unintentional manner the days in which local theater marquees were lit up with side-by-side juxtapositions of possibly not-so-related movie titles.

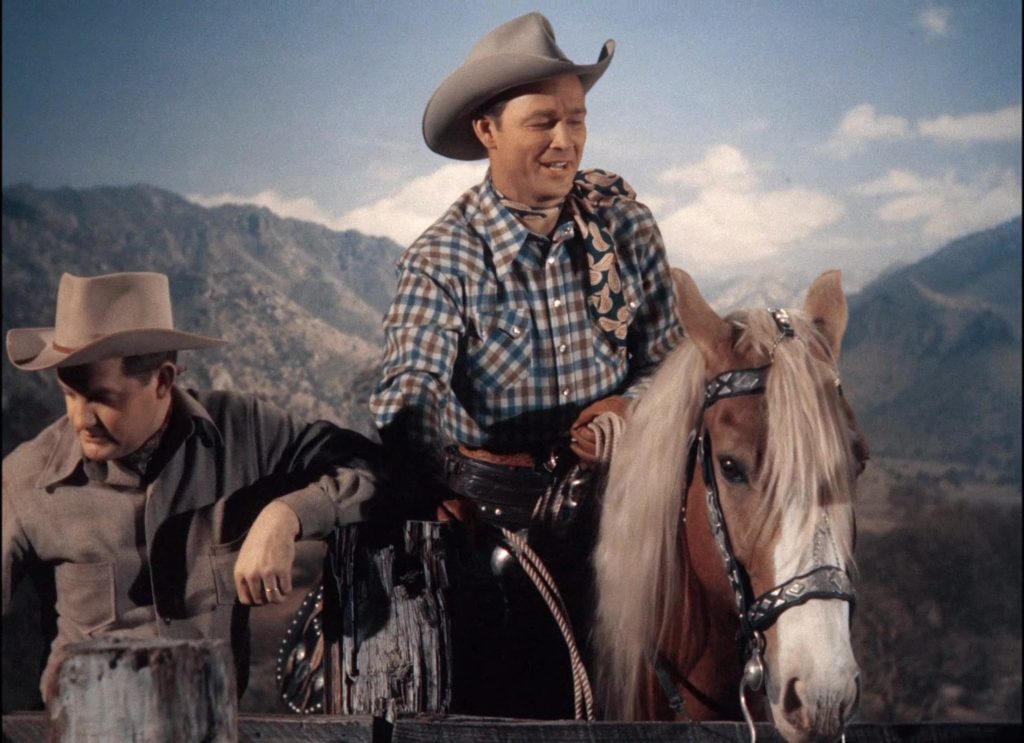

And while last week we might have had a Bela Lugosi melodrama smashed up against a screwball comedy, or a light musical accompanying a gritty war picture, today we have a Roy Rogers Western riding in front of a moody thriller. From the TruColor vistas of a mythic West to the shadow-casting mean streets of the inner city, the classic B-picture delivered precisely what their audiences expected, while with equal precision evoking the fictional realities from which they sprung.

…

In his commentary track accompanying Sunset in the West, Western/film historian Toby Roan claims that though Republic Pictures may have had three or more Roy Rogers Westerns in production at the time of its release, this is one of the very few that still exists in its original color-photographed and unedited form. Cut-down and color-desaturated for TV release, to coincide with the star’s popular weekly program The Roy Rogers Show (1951 – ’57), the original film elements of several of the famed Western balladeer’s movies, particularly those made after the mid-1940s, have regrettably aged and decomposed, and are now solely available for viewing in foreshortened, black-and-white versions.

In his commentary track accompanying Sunset in the West, Western/film historian Toby Roan claims that though Republic Pictures may have had three or more Roy Rogers Westerns in production at the time of its release, this is one of the very few that still exists in its original color-photographed and unedited form. Cut-down and color-desaturated for TV release, to coincide with the star’s popular weekly program The Roy Rogers Show (1951 – ’57), the original film elements of several of the famed Western balladeer’s movies, particularly those made after the mid-1940s, have regrettably aged and decomposed, and are now solely available for viewing in foreshortened, black-and-white versions.

Which is why this brand-new 4K scan of Sunset in the West is so valuable: reproducing the Western-set fantasies of an entire postwar generation of children with the visual fidelity of those Saturday matinee screens of yore, each lasso twirl, barroom brawl punch, and leaping horse-mount is once again fully endowed with the unequaled panache of a skilled group of artists and technicians who churned out stunts, thrills, and chills with seemingly effortless acumen. Clothes-lined to a tale of gun runners brought to justice by the upright and honorable Roy Rogers (playing himself, as he usually did in these modern-day Western musicals), the plot is appropriately thread-bare, but is marvelously upheld by expertly-choreographed Western action – courtesy of its director and genre specialist, William Witney – and a supporting cast of character actors – ranging from an incompetent barber/idiot sheriff’s deputy called “Splinters” (Gordon Jones) to an acidly-frilled cantina chanteuse named “Carmelita” (Estelita Rodriguez) – whose exchanges and personalities across a blissfully undemanding 67 minutes are such that I wish I had a big-enough brain and skilled-enough typing finger to reproduce them in full.

As it is, I’ll merely make my parting remark on Sunset in the West regarding Roy’s horse: never has an animal appeared to such advantage, displayed as much skill and charm, or was as lovingly photographed – in striking two-strip TruColor, no less – as the great blonde-mane Palomino bay, Trigger.

…

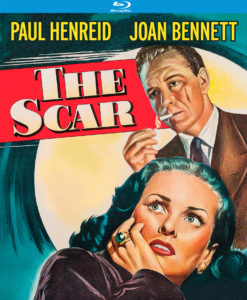

Film historian Imogen Sara Smith’s commentary for The Scar stresses the film noir’s theme of doubling, particularly its resonance with producer/star (and, reputedly replacing the credited Steve Sekely, possible co-director) Paul Henreid’s body of work – both here as an actor and later as a director (in 1964’s Dead Ringer) – but even a surface viewing reveals much to marvel at. And when that surface has been light-and-shadow sculpted by cinematographer John Alton – whose companion work at Poverty Row’s Eagle-Lion Films that same year, 1948, included the painterly films noir Raw Deal and He Walked By Night – the entrance into a world of smoky corridors, dungeon-like rooms, and fog-shrouded streets seems complete.

Film historian Imogen Sara Smith’s commentary for The Scar stresses the film noir’s theme of doubling, particularly its resonance with producer/star (and, reputedly replacing the credited Steve Sekely, possible co-director) Paul Henreid’s body of work – both here as an actor and later as a director (in 1964’s Dead Ringer) – but even a surface viewing reveals much to marvel at. And when that surface has been light-and-shadow sculpted by cinematographer John Alton – whose companion work at Poverty Row’s Eagle-Lion Films that same year, 1948, included the painterly films noir Raw Deal and He Walked By Night – the entrance into a world of smoky corridors, dungeon-like rooms, and fog-shrouded streets seems complete.

Progressively searching for some inner darkness beyond mere blackness with each low-lit scene, admirably reproduced and remastered for this Blu-ray release, Alton’s camera mercilessly records Henreid’s ambitious schemer John Muller and his nightmare descent into holdups-gone-awry, women-gone-astray (noir mainstay Joan Bennett), and plots-gone-haywire as the overconfident criminal is drawn ineluctably towards his exact physical (and metaphysical) double in one scar-faced Dr. Bartok (also Henreid). Secondary to a plot that strains the bounds of credulity with each marvelously preposterous turn, screenwriter Daniel Fuchs’ literate dialogue (which includes the immortal film noir line “it’s a hollow little world”) and an atmosphere literally soaking in dread puts The Scar, doubling its suggestive qualities further with the alternate titles Hollow Victory and I Murdered Myself, in a class with Fritz Lang’s earlier Scarlet Street (from 1945, also co-starring Joan Bennett) and Robert Siodmak’s later Criss Cross (from 1949, also written by Daniel Fuchs).

from director Joseph H. Lewis’ THE BIG COMBO (1955); photographed by John Alton

Like those films, and as a crime melodrama that doesn’t cop out in the final act on the name later given to the style and genre, it ends badly. Which, of course, is as it should be in a style and genre which means “dark film”.

…

Tapping entirely different though equally pleasurable points in the movie-watching brain, these two genre efforts, again, accomplish exactly what they set out to accomplish in the manner and presentation of their respective genres. Making a case for low-budget filmmaking, and the skillfully imaginative efforts of its practitioners, our Sunset in the West and The Scar double bill puts the lie to fictional producer Jack Lipnick’s shame over the term “B-Picture”.

Sometimes “B”, as it turns out, is “Best”.

The images used in this review are used only as a reference to the film and do not necessarily reflect the visual quality of the Blu-ray.