One Cat… Who Plays Like an Army! On Blu-ray!

DIRECTED BY IVAN DIXON/1972

STREET DATE: October 18, 2016/KINO LORBER STUDIO CLASSICS

In 1978’s super-dumb but nevertheless influential book The Fifty Worst Movies of All Time, ultra-conservative critics Harry and Michael Medved had the temerity to include complicated masterpieces like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point and Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad in their misguided overview. But they really stepped into some bad mojo by slagging off Ivan Dixon’s Trouble Man, I guess owing to their innate fear of a black planet. But Trouble Man is no worse than many entries into that ’70s-centric genre known as Blaxploitation (I’ve always found that term irritating; there’s nothing exploitative about these films). Trouble Man never comes close to the worst dregs that cinema has to offer. In fact, it’s stylish and entertaining, if not as much as more essential genre entries like Shaft, Coffy, Dolemite, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

In 1978’s super-dumb but nevertheless influential book The Fifty Worst Movies of All Time, ultra-conservative critics Harry and Michael Medved had the temerity to include complicated masterpieces like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point and Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad in their misguided overview. But they really stepped into some bad mojo by slagging off Ivan Dixon’s Trouble Man, I guess owing to their innate fear of a black planet. But Trouble Man is no worse than many entries into that ’70s-centric genre known as Blaxploitation (I’ve always found that term irritating; there’s nothing exploitative about these films). Trouble Man never comes close to the worst dregs that cinema has to offer. In fact, it’s stylish and entertaining, if not as much as more essential genre entries like Shaft, Coffy, Dolemite, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

Ivan Dixon was a fascinating figure in the world of black cinema. Most famous for being part of Bob Crane’s band of conniving WWII POWs in the mid-60s TV hit Hogan’s Heroes, this movie-star handsome actor (the Idris Elba of his day) made notable contributions to two Sidney Poitier vehicles, the superb 1961 film version of Lorraine Hansberry’s Broadway hit A Raisin in the Sun, and 1965’s Oscar-winning tearjerker A Patch of Blue. He’s most memorable in 1964’s landmark love story Nothing But a Man, opposite singer/actress Abbie Lincoln in Michael Roemer’s heartfelt chronicle of a romance doomed by the couple’s increasingly dour economic prospects. After being nominated for a Lead Actor Emmy in 1967 (for The Final War of Olly Winter, a now difficult-to-find episode of CBS Playhouse), he stepped up to directing episodes of The Bill Cosby Show and the acclaimed high school dramedy Room 222, becoming the first black director to be afforded such newly-opened opportunities.

Where the Blu-ray really pops is in the film’s brightly-colored costumes. Is it weird to love a movie for this reason? Who cares?

1972’s Trouble Man would be one of only two cinematic efforts by this pioneer (the second being an incendiary 1973 film, The Spook Who Sat By The Door, about a black revolutionary’s efforts to infiltrate the CIA). One suspects that the blooming Blaxploitation genre failed to offer this clearly thoughtful director enough humanism to chew on, and so he abandoned movies to concentrate on television, where he went on to helm many episodes of whiter-than-white series like The Waltons, Magnum P.I., The Rockford Files, and The Greatest American Hero. Trouble Man is no masterpiece, but Dixon had nothing to be ashamed of; like many films of its genre and period, it’s a lot of fun.

A stern Robert Hooks plays our chic, straight-talking hero, Mr. T (we never find out his real name; I suppose it is Trouble). It’s difficult to determine what the man actually does for a living—he’s not a detective or a crime boss. He inhabits a murky in-between state as the tough go-to asskicker when things turn stormy in the Los Angeles underworld. The movie’s first lines were probably pretty hilarious in 1972: he’s approached by Billy Chi (Akili Jones), a henchman for street boss Chalky (Paul Winfield). Billy says “Chalky sent me to say he wants to see you on some business, Mr. T.” Hooks’ response: “You go tell Chalky he can kiss my black ass.” The Medved book lists this as some of the film’s “bad” dialogue, but it feels pretty prophetic to me. And there’s a lot more of this kind of steely talk herein.

It turns out Chalky wants Mr. T to track down a team of hoods overturning the profitable craps games run by he and Pete Cockrell (a slimy Ralph Waite). Riding in T’s gorgeous white Cadillac, Chalky contracts with T a hit deal with a payout of $10,000. Yet you can just glance at ferret-like Waite, with his color-coordinated glasses hiding those hinky blue eyes, and you know something more odious is up, even if the sweatier, more genuflecting Winfield is in cahoots (it’s illuminating to remember that, in 1972, Paul Winfield became among the first black actors nominated for the Best Actor Oscar for Martin Ritt’s gentle Sounder, while Ralph Waite was toiling away on CBS’ The Waltons, another warm, rural-set family drama). Anyway, soon Mr. T is sniffing at the heels of another LA player Mr. Big (Dixon’s Nothing But a Man co-star Julius Harris, excellent) and, in the pool hall that serves as T’s unconventional office, there’s a mid-film confrontation that confirms our worst suspicions (I found myself really rooting for Bill Henderson’s Jimmy, the overseer of the pool hall).

I love the black action films of this period, and Trouble Man, in its newly polished Kino Lorber Blu-ray iteration, rewards such adoration. First of all, it’s essential to note the film provides us with the only big-screen score composed by R&B legend Marvin Gaye. Gaye’s work doesn’t approach the brilliance of Isaac Hayes’ magnificent orchestrations for Gordon Parks’ Shaft (most of the work here sounds like sub-par TV movie music). But Trouble Man does sport a spectacularly jazzy, extremely memorable title song which became one of Gaye’s biggest hits (the radio version concentrates on Gaye’s perfect falsetto voice but, here over the film’s credits, we’re treated to a track with Gaye’s deeper harmonics taking an unfamiliar lead).

I love the black action films of this period, and Trouble Man, in its newly polished Kino Lorber Blu-ray iteration, rewards such adoration.

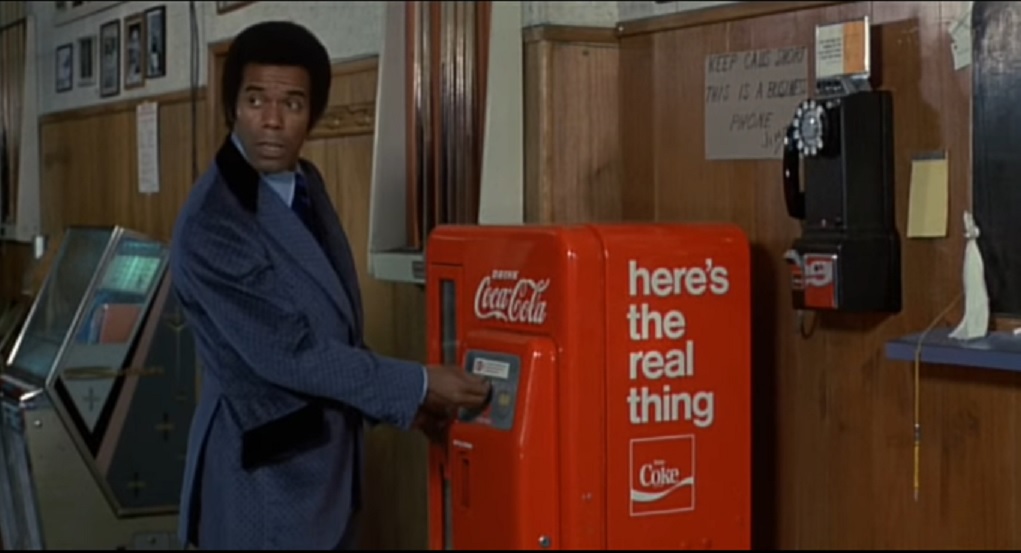

Where the Blu-ray really pops is in the film’s brightly-colored costumes. Is it weird to love a movie for this reason? Who cares? The threads here are absolutely stunning. Mr. T is a man for whom style is clearly a predominate concern, whether he’s scampering up a villain’s dumbwaiter or dropping 15 cents for a Coca-Cola from his pool hall’s vending machine. He makes sure to carry a clean set of dry-cleaned clothes in his Caddy’s trunk, and so Robert Hooks, his modest afro always tidy, never appears anything less than totally put together when the shit goes down.

The Blu-ray seems to compliment the color coordination in not only his wardrobe, but in that of all the other characters. The villains look sparkly and bright. The background players goose the drab pool hall set with lovely pinks and purples. T’s patient woman (Paula Kelly) pops in one scene dressed in a tight lime green dress that clashes wonderfully with her African-accented yet modish apartment, a red patent-leather couch in its center. In T’s bedroom, the eyes marvel at the silvery wallpaper reflected in the room’s copious mirrors. In the end, I found much joy in Trouble Man‘s ultra-70s costuming and art direction. And I have to say—as 70s-era black films go, this is one without an overload of tits (actually, no nude scenes), blood (a ridiculously fakey red), and harsh language. It’s a Blaxploitation movie for the whole family, by today’s standards.

The restoration here isn’t perfect—I still caught occasional scratches and smudges, and low-light scenes are notably grainy. But, hell, I like it when movies look like this. Plus we get a smart, informative commentary from film historian Nathaniel Thompson (of Turner Classic Movies’ Movie Morlocks) and Life and Death of Joe Meek director Howard S. Berger, as well as a choice collection of trailers ranging from a generous five-minute peek at Isaac Hayes’ starring vehicle Truck Turner to a gritty glimpse at Ossie Davis’ Cotten Comes to Harlem and Barry Shear’s Across 110th Street. I don’t care what anyone says—Medveds be damned—Kino Lorber’s new Blu-ray proves that Trouble Man is a low-key blast that reminds us of the streetwise gifts black cinema offered us in the 1970s.

The images used in the review are present only as a reference to the film and are not meant to reflect the actual image quality of the Blu-ray.