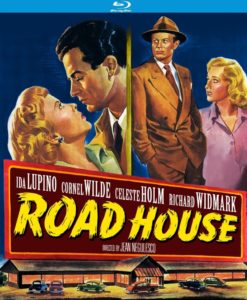

Film Noir Fantasy Delights With Canny Casting And Bizarre Backdrop

DIRECTED BY JEAN NEGULESCO/1948

STREET DATE: September 13, 2016/KINO LORBER

Not in any way (repeat: ANY WAY) to be confused with the late-’80s beer-and-bouncers epic of the same title, the late 1940s Road House is somewhat lesser-known among film noir titles of the period, but should be counted among the more bracingly unusual and unusually effective entries of both the style and genre. With its vividly unrealistic, studio-bound Pacific Northwest milieu, the roadside establishment described by the title comes complete with gleaming, chromium-plated surfaces, a backwoods antlers- and moosehead-mounted walls motif, and a side-by-side combination-nightclub piano bar and bowling alley. Equal to the baroque and smoky atmosphere created by the dizzying mixture of upscale, rural, and strangely suggestive set design are its appropriately uninhibited inhabitants, who include its one-and-only-named owner Jefty (Richard Widmark), his stalwart right-hand man Pete (Cornel Wilde), their reliable cashier Susie (Celeste Holm), and tough-as-nails professional chanteuse Lily Stevens (Ida Lupino). The psychodrama that unfolds between the four characters in this dreamlike setting represents Hollywood at its weirdest and wildest: a slow-burning fuse lit by a glimpse of a shapely, nylon stocking-clad lower limb spread casually over a desk in its opening moments to a jealousy-ridden, giggling madman stalking through brush and bramble, guns-a-blazing, towards its scene-searing conclusion.

Not in any way (repeat: ANY WAY) to be confused with the late-’80s beer-and-bouncers epic of the same title, the late 1940s Road House is somewhat lesser-known among film noir titles of the period, but should be counted among the more bracingly unusual and unusually effective entries of both the style and genre. With its vividly unrealistic, studio-bound Pacific Northwest milieu, the roadside establishment described by the title comes complete with gleaming, chromium-plated surfaces, a backwoods antlers- and moosehead-mounted walls motif, and a side-by-side combination-nightclub piano bar and bowling alley. Equal to the baroque and smoky atmosphere created by the dizzying mixture of upscale, rural, and strangely suggestive set design are its appropriately uninhibited inhabitants, who include its one-and-only-named owner Jefty (Richard Widmark), his stalwart right-hand man Pete (Cornel Wilde), their reliable cashier Susie (Celeste Holm), and tough-as-nails professional chanteuse Lily Stevens (Ida Lupino). The psychodrama that unfolds between the four characters in this dreamlike setting represents Hollywood at its weirdest and wildest: a slow-burning fuse lit by a glimpse of a shapely, nylon stocking-clad lower limb spread casually over a desk in its opening moments to a jealousy-ridden, giggling madman stalking through brush and bramble, guns-a-blazing, towards its scene-searing conclusion.

Twentieth Century-Fox had at that point released a whole slew of realistic docudramas purporting to recreate crime and espionage-related post-wartime activities. With their stentorian narration, time-checking plot structure, and straightforward depiction of the law enforcement process, films like House on 92nd Street (1945), Boomerang! (1947), Call Northside 777, Street With No Name, and The Naked City (all 1948) stood in stark contrast to the more florid and melodramatic style of the studio’s earlier Laura (1944) and Fallen Angels (1945). The latter pair had been photographed by Joseph LaShelle, who with Road House definitively broke with the documentary house style the studio had cultivated in the interim and instead went for broke with the shadowy atmosphere traditionally associated with noir, creating a heightened sense of reality effectively complementing the increasingly heightened emotional content of the drama. The painterly compositions and brittle handling of director Jean Negulesco, a respected screen stylist who proved his mettle with atmospheric melodramas like The Mask of Dimitrios (1944) and Three Strangers (1946), as he later would with the technical demands of CinemaScope, add to the tension-filled nature of the production by dramatically emphasizing the developing sexual attraction between Pete and Lily, even as Jefty descends further into the trap of sexual jealousy.

And it is at this point that the casting takes over and literally rides roughshod over the script: with dependable screen anchor Cornel Wilde, as Pete, smack-dab in the middle, the dynamic and unpredictable Richard Widmark, as the unstable and manipulative Jefty, is jolted into dark and dangerous action by the bewitching Ida Lupino as the throaty-voiced singer Lily. Lupino, in her first role for Fox after a decade of overlooked brilliance at Warner Brothers, offers a screen-commanding presence reminiscent of Humphrey Bogart at his most world-weary unconcerned and Robert Mitchum at his most sleepy-eyed cool. Smart, supremely capable, AND sexy (some of her strapless outfits and form-fitting gowns may cause viewers to blush even in 2016), the more incredible and unbelievable plot developments of the melodramatic goings-on are rendered frank and believable by the supremely confident playing of Ms. Lupino. Two moments in particular, where, early on, Lily croaks out “One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)” may convince one of hidden depths in an even-then well-worn lyric and, later on, where Lily gets the better of Pete on his natural terrain of the bowling alley, prove this to be a woman worth both fighting for and losing one’s mind over. In an otherwise thankless role, the Academy Award-winner for the previous year’s Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), Celeste Holm as Susie, is at least allowed to sum up the unconventional appeal of a character upon whom the fulcrum of the drama rests: “She does more without her voice than anybody I ever heard.”

Viewers unfamiliar with the movie, but possibly intrigued by some of the content described above, are strongly referred to Kino Lorber’s upcoming Blu-ray of the film, which had been previously released as one of the later “Fox Film Noir” entries on DVD in 2008. In particular, the feature-length commentary, and interplay, between noir experts Kim Morgan and Eddie Muller is almost as entertaining as the film itself, and, indeed, the information, trivia, insights, and theories batted around between the participants has so colored this humbled, to-be-pitied reviewer that he is much afraid to continue with the review for fear of plagiarizing their imaginative, deep-viewing ideas. (I only wish I could allude to Mr. Muller’s thoughts on the backstory between Jefty and Pete, or Ms. Morgan’s solid and passionate defense of the film’s wooly third act.) Having previously encountered this film through the aforementioned DVD release, I can unequivocally state that the Blu-ray is worth the upgrade, both visually heightening Joseph LaShelle’s photography in key, subtly-lit and studio-controlled “outdoor” sequences, and aurally improving the effect on the road house rowdies of Lily/Lupino’s standard-making rendition of the timeless “Again”. A joint documentary on Ida Lupino and Richard Widmark, along with a trailer gallery of (hopefully upcoming) noir releases, round out the contents of the Blu-ray’s special features, and serve to put a home viewer into an appropriately “noir” frame of mind, whether viewed before or after the main feature.

As a final thought, though it may be wishful thinking, one can further hope that when one hears the movie title Road House, an image of Ida Lupino in a scarf-makeshift bathing suit may one day replace that of a mullet-haired Patrick Swayze.

The images used in the review are present only as a reference to the film and are not meant to reflect the actual image quality of the Blu-ray.