Recording Artist Meets Recording Artist With Not Much To Say

DIRECTOR: LIZA JOHNSON/2016

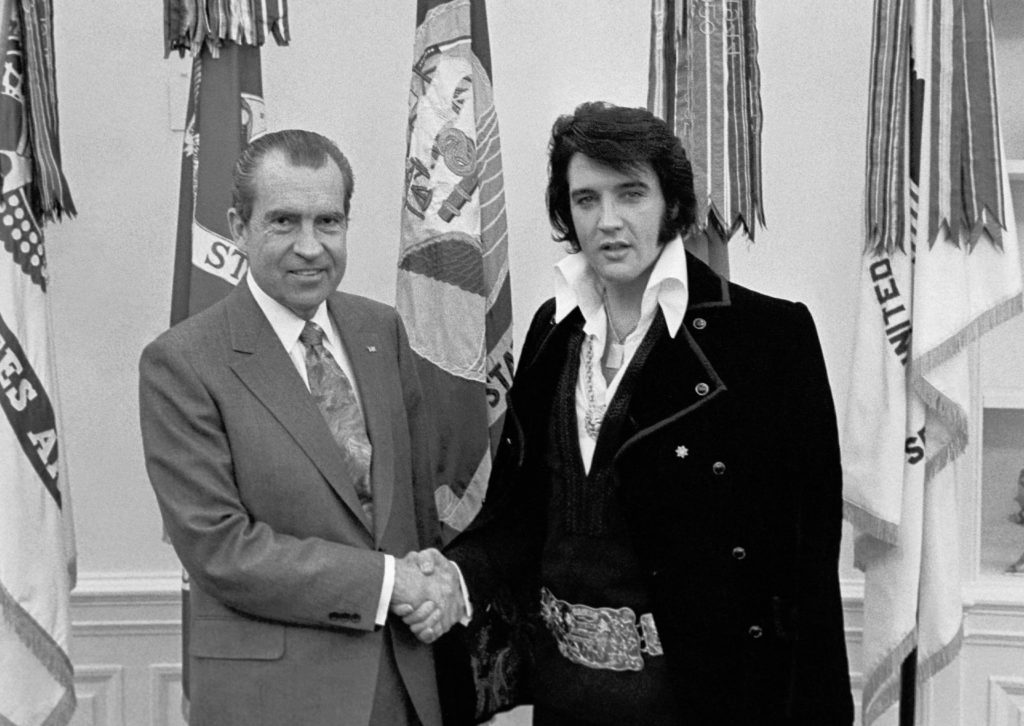

They say the picture of Nixon shaking hands with Elvis in the Oval Office is the most-requested item from the National Archives. I predict the movie speculating on the backstory of that rarified moment won’t be so beloved. Elvis & Nixon puts forth apocryphal assumptions of how and why Elvis managed to maneuver past the wall of paranoia that was the Nixon White House, hoping to become a “Federal Agent-at-Large” in order to go undercover amongst his own celebrity circles. The movie, as was the actual event, is set in December 1970, before Nixon had fully installed his now-infamous Oval Office recording system, so the reasons for the granting of the meeting and the content of the eventual conversation are left to the imagination of the screenwriters. Unfortunately for anyone who nurtures a real appreciation for the overwhelming richness of these two idiosyncratic monoliths, the writers, who have a supreme opportunity to concoct some choice banter, play it instead as a quick, barely-scratched-surface intersection of awkward groping for common ground, and the titular photo-op finally flops, neither funny nor especially interesting.

National Archives. I predict the movie speculating on the backstory of that rarified moment won’t be so beloved. Elvis & Nixon puts forth apocryphal assumptions of how and why Elvis managed to maneuver past the wall of paranoia that was the Nixon White House, hoping to become a “Federal Agent-at-Large” in order to go undercover amongst his own celebrity circles. The movie, as was the actual event, is set in December 1970, before Nixon had fully installed his now-infamous Oval Office recording system, so the reasons for the granting of the meeting and the content of the eventual conversation are left to the imagination of the screenwriters. Unfortunately for anyone who nurtures a real appreciation for the overwhelming richness of these two idiosyncratic monoliths, the writers, who have a supreme opportunity to concoct some choice banter, play it instead as a quick, barely-scratched-surface intersection of awkward groping for common ground, and the titular photo-op finally flops, neither funny nor especially interesting.

The movie is ultimately only entertaining insofar as its subjects are two endlessly fascinating people. By the point in their lives depicted in Elvis & Nixon, Elvis had codified rock and roll as a cultural force, Clambaked and Creoled over a decade of fun but charisma-squashing movies, and then emerged again in 1968 from his leather chrysalis, in mid-bloom toward becoming the epitome of Vegas-style uber-showmanship, validating his Kingship in sequins and collars. Meanwhile, Nixon had endured decades of political corrosion, much of it brought upon his own sweaty brow, ascending through the ‘40s and ‘50s from Congressman to Vice-President, only to lose a bid for the presidency to Kennedy, lose a bid for the governorship of California to Pat Brown, nose-thumb the press with the pronouncement, “You won’t have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore,” and recede into the wilderness of the ‘60s, then finally escaping his own cocoon – also in 1968 – to sock it to his myriad enemies by at last nabbing the White House. Elvis and Nixon were both, essentially, masters of reinvention, men with egos that compelled them to continue despite the public’s fickle love. But this movie is too thin to go that deep, opting instead to highlight that both live in big houses and enjoy a good nap.

Played by the great Michael Shannon, Elvis is, sadly, mishandled. I can see where he’s going with it – trying to work around the easily impersonatable movements and mumbles that are the de facto “object” of who he was, to find some level of depth. Elvis, as revealed in interviews and documentaries, was a gentle, funny man who just happened to also have enough charisma, talent, and skeletal flexibility for the entire world to not help falling in love with him – but he never lost that core quality: the Mississippi boy who adored his mama and revered gospel music. But Shannon’s Elvis is much less charming than he thinks he is, and much more off-puttingly creepy. It’s not just that he looks nothing like Elvis, it’s that the thought coming through his eyes and body language is not sweet-but-dangerous, like the King, but emaciated-and-cornered. If this was a movie about the depletion of the man’s basic essence – and indeed there are two scenes that speak to this – the tack would be welcome. But in a simply amusing, otherwise defiantly uncomplicated comedy, it comes off as a miscalculation. Case in point, karate. Elvis’s famous later-in-life obsession with the discipline, broadcasting his moves via worldwide television concerts, is really an unnecessary quirk for the man who practically invented stage presence, yet it still works as an extension of his goofy, glibly self-aware energy. In the movie, the way Shannon employs the random kick or extended power-hand makes him seem like a sad man hanging on to some shtick he got a laugh with at a party ten years ago. That hand, tossed up and into the faces of random interlopers, is like some kind of ineffectual Jedi mind trick. With Shannon’s brand of quiet, leering intensity, this Elvis never comes off as funny or endearing.

Played by the great Michael Shannon, Elvis is, sadly, mishandled. I can see where he’s going with it – trying to work around the easily impersonatable movements and mumbles that are the de facto “object” of who he was, to find some level of depth. Elvis, as revealed in interviews and documentaries, was a gentle, funny man who just happened to also have enough charisma, talent, and skeletal flexibility for the entire world to not help falling in love with him – but he never lost that core quality: the Mississippi boy who adored his mama and revered gospel music. But Shannon’s Elvis is much less charming than he thinks he is, and much more off-puttingly creepy. It’s not just that he looks nothing like Elvis, it’s that the thought coming through his eyes and body language is not sweet-but-dangerous, like the King, but emaciated-and-cornered. If this was a movie about the depletion of the man’s basic essence – and indeed there are two scenes that speak to this – the tack would be welcome. But in a simply amusing, otherwise defiantly uncomplicated comedy, it comes off as a miscalculation. Case in point, karate. Elvis’s famous later-in-life obsession with the discipline, broadcasting his moves via worldwide television concerts, is really an unnecessary quirk for the man who practically invented stage presence, yet it still works as an extension of his goofy, glibly self-aware energy. In the movie, the way Shannon employs the random kick or extended power-hand makes him seem like a sad man hanging on to some shtick he got a laugh with at a party ten years ago. That hand, tossed up and into the faces of random interlopers, is like some kind of ineffectual Jedi mind trick. With Shannon’s brand of quiet, leering intensity, this Elvis never comes off as funny or endearing.

The source material.

Kevin Spacey’s Nixon suffers, too. If Shannon’s Elvis comes up short, it can at least be called a “characterization” – the taking of familiar idiosyncrasies and giving them your own spin. A keen example of this is Will Ferrell’s George W. Bush on Saturday Night Live, so twisted up in Ferrell’s own comic sensibility that his W becomes non-W, or W-plus. But what Spacey does with his Nixon is more akin to a Rich Little impersonation, a more self-consciously faithful employment of mannerisms to hew as close to the original as possible. It’s fun to watch, since, by now, we’re primed to enjoy Spacey-as-impersonator from interviews and talk shows. Against Shannon’s strangeness, though, it’s a conflict of tones that drains their scenes together of needed chemistry. And for poor Spacey, there’s just not enough room (all his few scenes are in the Oval Office) to make anything more of him than a highlight reel of Nixonese. It’s like director Liza Johnson was actively working hard to squelch any comic payoff.

We can’t complain too much that culture has stripped down these two rich and mammoth ‘70s icons into easily imitatable caricatures. But we can fidget when a movie tries to transcend that two-dimensionality by replacing it with a different two-dimensionality. Granted, we’re inside a comedy, so the two-dimensionality of it all is acceptable to a point. But when both actors, especially Shannon, could be trying for something more, but are surrounded by the director’s flat execution and the uncreative dialogue of the script, relative to what it could have been, then the performances become mostly unmoored, confusing, and, in the final meet-and-greet, thuddingly anti-climactic. Elvis & Nixonis a harmless sketch comedy that should have had more satiric bite.