Evil Taketh Many Forms

ERIK YATES: If thou hast a differing view of God, our creator, and our relationship to the thou Almighty, then thou shall no longer be welcome to fellowship amongst us. Thou must leave the comforts and the shelter of our safe colony and thou must wander in the wilderness, shamed from returning lest ye repent of your evil pride. Then, and only then shall ye be able to return.

ERIK YATES: If thou hast a differing view of God, our creator, and our relationship to the thou Almighty, then thou shall no longer be welcome to fellowship amongst us. Thou must leave the comforts and the shelter of our safe colony and thou must wander in the wilderness, shamed from returning lest ye repent of your evil pride. Then, and only then shall ye be able to return.

The above paragraph describes the opening scene of the latest horror film, serving as a New England cautionary tale. The “King James” English of the above paragraph is a sample of what you will experience throughout the film due to its timeframe and setting. Taking place in 1630, roughly 62 years before the infamous Salem Witch Trials, The Witch tells the story of a devoutly Christian puritan family whose practice of Christianity is so rigid that they no longer wish to be a part of the colony church. As a result they choose to leave the comforts of the colony and seek to strike out on their own in the new American wilderness.

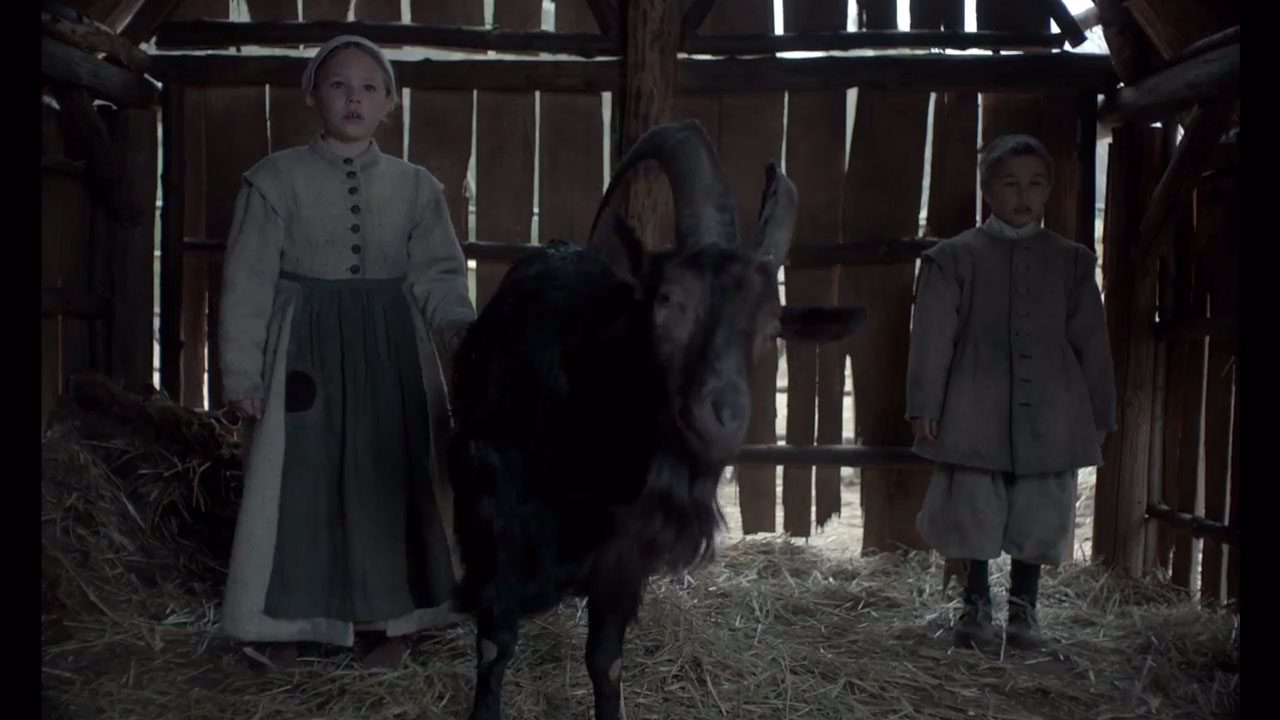

Finding a comfortable spot with a brook for water and crops, and surrounded by a forest of trees, William (Ralph Ineson – Kingsman: The Secret Service, Guardians of the Galaxy, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2) settles down with his wife Katherine (Kate Dickie-Prometheus), oldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy of Vampire Academy), son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), twins Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), and their newborn baby son. Here they will be free to practice their faith and be self-sufficient. Everything is going well until their newborn goes missing. It is here that everything begins to unravel.

The horror of this tale is not the jump-scare type manipulation that one is used to in more recent mainstream fare such as Insidious, or Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones. Director and Writer Robert Eggers (Short films The Tell-Tale Heart, Hansel & Gretel) seeks to make this a 17th century nightmare as would exist back then. The horror elements are far more subtle and contain just as many internal demons such as struggling with one’s faith, and simple minded boogeymen type tormentors than the external threat a real witch or even demon might be. As a result, Eggers is able to keep the tension of the horror throughout the film, despite having to rarely show the titled antagonist. This is a real strength of the movie considering its extremely modest budget.

JIM TUDOR: I’d agree most assuredly with thine confident assessment, good brother!

(I don’t know that the King James schtick is for me…)

Immediately after seeing The Witch, my first thought was to compare it to last year’s Ex Machina. Although they are of separate genres, both tremendously utilize everything at their artistic disposal – production design, cinematography, and perhaps most vitally, great performances – to tell their bold yet contained tales with all the courage of their first-time feature filmmakers’ convictions. Both films spotlight young actresses to make uneasy statements about women in culture. They are each arguably the first truly strong movies of their release years, and both deserve to be remembered at the end of their respective years when critics are making their “Best of” film lists.

The similarities end there. Having seen a trailer for The Witch a while ago, and having caught a whiff of the buzz surrounding the film, I found myself actually a bit scared of it. (And this is coming from a horror film veteran of many decades!) I hadn’t even seen it yet, and already it was casting its spell on me.

The day I was to see it, a self-proclaimed Satanic organization claimed the film as their own, touting it as a favorable depiction of their values, a list which included “female empowerment”. The pairing of female empowerment with Satanism is more likely irresistible negative accusatory fuel for certain religious fundamentalists than favorable movie marketing, but nonetheless, my caution lingered. Could The Witch be the film that Billy Graham should’ve waited for when he so infamously denounced 1973’s The Exorcistas (I’m paraphrasing here) “harboring demonic evil within it’s very celluloid”? Knowing full well that the most effective thing any horror film can do for itself is convince the viewer that he/she is in the hands of an unstable filmmaker, I prayerfully proceeded to the theater. Who is Robert Eggers, and what is he trying to do here?

On the way to and from the screening, the atmosphere outside nearly matched that of Egger’s film. Although it’s true that the conditions surrounding any given film exhibition will affect our interaction with it on some level, this proved to be an aid that The Witch simply didn’t need. With it’s palpably muted opaque cloud of dread hanging heavily over every frame, and a premise that is at once tremendously alien to the contemporary world (the buttoned up, rigid New England religious mindset threatening to give way to superstition coupled with the farming life of yore), yet all too relatable (the perils of isolationism), the film is of a piece, and very much one with itself.

To be clear, yes, The Witch is a scary film. It’s the kind of scary that is prone to lingering under the skin, resurfacing to pronounce itself unexpectedly. That said, I don’t know that it’s quite as “profoundly scary” as it’s marketing, its reputation, and/or the Satanists would have us believe.

It is, after all, a fictional tale and, beneath its authentic veneer, a clearly meticulously crafted film. The 1630 vibe and set decoration are downright Jack Fisk-ian (the great production designer of rustic period films such as The Revenant and The New World), and as it should, aids in the unrelentingness of the experience. Look hard, and one can see the “cinema” in it all. In other words, The Witch, while downright effective on the whole, is still only a movie. (“Only a movie…! Only a movie…! Only a movie…!”)

ERIK YATES: I too had read about the Satanist-sponsored screenings and found it an odd thing in some of the ways you mentioned. In other ways, I can totally see the appeal of that group, if one takes a surface level understanding of the larger themes of the film. To explain that, I’d have to divulge spoilers, so I’ll refrain for now, though I plan on discussing this further in a Reel Theology article on this next week. Either way, it seems an odd pairing.

I agree that the comparison with Ex Machina is a good one. It works as a subtle commentary of the very themes you mentioned. And this is why it is scary. Its marketing seeks to put it in a barrel with other jump-scare films of the day, but it is the social commentary running throughout the narrative that casts its spell across the entire experience and causes us to wrestle with some very core themes like the effect of isolationism, doubt, pride, anger, resentment, longing, and fear of the unknown.

The actual witch needs very little screen time as these themes are able to occupy the protagonists enough to create the conditions necessary for final conclusion. What may drag down the enthusiasm of the typical horror film fan may be the very King James-ian dialogue that permeates the entire story (and a couple lines of this review), and the open-ended way in which the story concludes in terms of the broader themes I mentioned. But as you are saying Jim, this is a refreshing take by a first-time feature length director in a genre that could frankly use a real shake-up and redefinition following a decade and a half of found footage type scares that proceeded out of Hollywood studios to copy the indie success of another witch, namely The Blair Witch Project.

For a genre that is broad enough to handle everything from slasher, to apocalyptic, to demonic, to psychological fear, it is stunning that it has taken so long to have something really fresh to say. The Witch provides that, ironically by going way back to a time where you couldn’t use gimmicks, electronics, or the like. The evil here is external, but more often than not it is the very human condition that is in each of us that makes it so relatable and palpable, despite its 1630 setting.

JIM TUDOR: It certainly is all of that, and plenty more. Eggers has crafted something truly memorable, something scary, and something that is somehow worthwhile. Is it Satanic? I have no idea. Back in 2000, I admired The Cell by Tarsem Singh for many of the same reasons, and later discovered that is in fact reportedly built on a firm foundation of paganism. About that I can only speculate on how such knowledge would’ve altered my perception and endorsement of it. I can say with confidence that when it comes to the dread it conjured, my admiration remains as intact ever. Such is certainly the case with The Witch. To step back even further into film history, those familiar with the work of Carl Theodore Dreyer could consider it the anti-Ordet.

It’s been said that there are movies that are about evil things, and then there are movies that are simply evil. As in, fundamentally warped, twisted, dark… to their very core. After our screening, it was proclaimed by someone other than myself that The Witch is one of the purely evil ones. While I know what he means, and even agree 9/10s of the way, there’s that one tenth that can’t go with that, as Irefuse to buy that Robert Eggers is an evangelical devil worshipper with a movie camera and a love of death. I what I do believe is that he’s someone who understands how to make even the most jaded horror fans excited, curious, and even trepidatious about a new movie.

From that angle alone, The Witch is a thing of genius. It is a slow, brooding film that isn’t afraid to go sinister. It cultivates in the viewer the same corrosive suspicion that infects the characters in the story. It tears away at what we value, and does so without compromise. Those looking for the usual good-triumphing-over-evil paradigm should look elsewhere, as should those seeking cheap thrills alluded to by the female silhouette on the poster. This is a lean movie that isn’t screwing around, but also doesn’t feel any need at any point to explain itself.

As a downcast portrayal of a sheer puritanical nightmare scenario, The Witch presents quite effectively indeed as something of mystical evil. It demonstrates the worst horrors inherent in removal from community. The religious lives and beliefs of this family, ostracized from their circle in the film’s early moments, can be cited as to being part of their downfall – and that’s accurate – but the fact of the matter is that the issue of their beliefs, and the rules and structure that come with that, are not as removed from our own infinitely more secular times. Modern day “evil” – ignorance, self-centricity, material greed, and the perceived entitlement that comes with all of those – simply isolate us in different ways. Each of us must ask ourselves to what degree we will give ourselves over to those things. The Witch, as “evil”, as strange, as old-world as it presents itself, is not so removed from 2016 as we may think.

Those with the spirit to venture forth into the dark of The Witch‘s favored cinema will confront with thine eyes and thine heart a filmic evocation of darkness brought forth by pure solidarity of vision. Lo, the filmic tale bucks and kicks like an animal possessed, but it also sits and stews like a coven in waiting. And just as film reviewing in the King James dialect is not for me, The Witch is not for everyone. For those it does recruit, it will, on some level, bewitch.