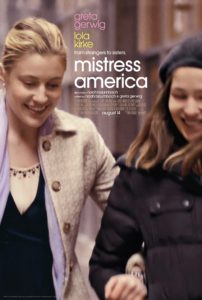

A Screwball Comedy For The Delusional Drifter

DIRECTED BY NOAH BAUMBACH/2015

Ennui, ennui, ennui, ennui, ennui.

Ennui, ennui, ennui, ennui, ennui.

A little ennui by itself is, of course, boring by definition. But a whole carload of ennui – now that might be interesting to look at. Send that car to a fancy house in upper New York, and then you might really have something. So seems the reasoning behind the latest comedy from Noah Baumbach starring Greta Gerwig. This houseful of characters is perhaps bored without realizing it, maxed out on being self-reflective. Or, maybe they’re just busy – like the rest of us. In any case, Mistress America is not Frances Ha 2.

If one were to discuss it with the filmmakers, however, one would likely hear that its not being Frances Ha 2 is of course by design. The primary difference filmgoers may notice is that this movie is presented in color, Frances Ha is black and white. Although both spotlight New York City, and both star Greta Gerwig as a smart but scattered charmer who has it together to varying degrees.

“Mistress America” finds Gerwig as Brooke Cardinas, a terminally busy bee fluttering around a hundred flowers of in an afternoon. Except, the flowers are withering in-between cracks in the unrelenting New York sidewalks.

She speaks with sharp assuredness about her restraunt plans, her creative writing ideas (including a story called “Mistress America”), and her many other dizzying proposed endeavors. She’s the quick-witted center of attention that we always love for her to be, but it’s the underneath that really matters. If only she knew that. When it comes time to secure some emergency funds for her restraunt launch, she manages to completely talk around what any sensible person would want to know about it, instead manically selling the esoteric coziness she envisions. “And, it cuts hair!”

Fittingly, her character is given a showstopping (by comparison to the rest of this street level production), Gatsby-esque entrance into the story, striding confidently, arms outstretched, down a bright red staircase, radient in her off-white overcoat. That’s about fifteen minutes into the altogether short 84 minute film.

“Welcome to the great white way!”

Before that, we’re tethered to Mistress America‘s actual lead character, the altogether unappealing first-semsester college girl, Tracy Fishko (played by Lola Kirke). As we wait for Gerwig to eventually enter the picture, Baumbach’s tonal mistep of asking someone who’s not Gerwig to lay the groundwork for this contemporary screwball comedy that plays in the unique key of Gerwig resounds with desperation.

Rejected by any potential friends and boyfriends, Tracy resorts to cold calling her mother’s fiancee’s adult daughter and fellow NYC resident, Brooke. The two become fast soulmates, charting a believable course of female friendship from its skeptical inception to its later quakey hurtful revelations. Tracy is captivated by the thirty year old Brooke to the point of stealing her ideas, her demeanor, her ambition for her own piece of writing, something that she hopes to earn her entrance into her school’s prestigious literary society. Tracy is a solid writer, but not a solid person. This aspect of Mistress America might sound more compelling than it actually is.

Later in the story, the pair car-ride with Tracy’s friend and rejected paramour Tony (a likeable Matthew Shear) and his jealous girlfriend Nicolette (Jasmine Cephas Jones) to the upper New York home of Brooke’s wealthy aquintences, where all will be revealed. Or, most will be revealed. These characters may be incapible of not dwelling in their own fictionalized, better realities of their own lives.

The gang is all there, reading.

The film on the whole is both good and bad, feeling smart and sloppy, but never geling, never good enough. At times it’s a struggle, other times it pops with unexpected comedic delights. But, of all of the Wes Anderson/Noah Baumbach/Whit Stillman slate of films built on the internal unease of “are we laughing at these characters, or with them? Or both?”, this may be the first one to truly falter in that questioning. There’s an imbalance in this quick little film that points to a greater self-assurance and intellectual ambition, but misses the mark in nailing whatever that is.

You’re on the stage, now…

The ambition might be the familiar Baumbach theme of creative appropriation. Mistress America is screaming in its margins about homage. Or, as it’s sometimes thought of, theft. From lifting the David Bowie dance/run from French filmmaker Leos Carax for Frances Hato spending the second half of While We’re Young pondering the issue, it’s safe to say that the theme has wormed its way into his own work both in practice and and in observation. Baumbach is even friends with Brian De Palma, the cinema virtuoso who made his name in controversial homages to Alfred Hitchcock and others. (A fun nod to all of this: Look for the De Palma Dressed to Kill movie poster in a dorm room in Mistress America.) In the case of this film, the exploration may be as deep as what one character does with another’s work in the story itself. Or, as Alex Ross Perry points out in his Film Comment interview with Baumbach, The Great Gatsby looms large over the structure of the film. Additionally, one would be mistaken to rule out formative riffing on Jean Renior’s The Rules of the Game or even Cassavettes, Hawks, or Lubitsch as influences.

Anyhow, Mistress America seems to exist first to be clever about itself, and second to be entertaining. For the film to truly work, it would have to get out of its own way, but it seems to betoo much of a tossed-off effort to have that kind of discipline. Both Baumbach and Gerwig (who collaborated on this story and are said to be a couple in real life) are intellectual enough to know that genius can happen in a rush. But they’re wrong to assume that it’s the case this time. Mistress America has some great characters and funny lines and zippy moments, but on the whole it’s an amusing head-shaker of a movie, an art house puffball that blew in on the credentials of better, former work. But, at least it’s not boring.