Catching Up On The Maverick Auteur, 100 Years Strong

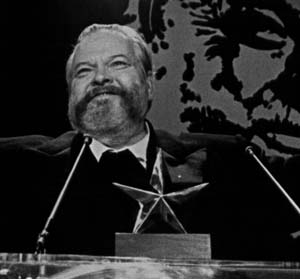

In 1975, the American Film Institute saw fit to honor Orson Welles with a lifetime achievement award. Welles, in his speech, took the opportunity to validate “the mavericks” of filmmaking, of which he was perhaps lead among, while at the same time saluting the machine they must work around. After all, what else could he do? By that point Welles had been rejected, for all intents and purposes, by Hollywood studio filmmaking. As early as his debut film Citizen Kane, he had been branded too solitary, too singular, too visionary. Too dangerous. He showed his face at the major studios only to take work as an actor for hire, a practice he engaged in order to financially support his independent directorial filmmaking efforts. As he affably put it in the speech, “in other words, I’m crazy.”

In 1975, the American Film Institute saw fit to honor Orson Welles with a lifetime achievement award. Welles, in his speech, took the opportunity to validate “the mavericks” of filmmaking, of which he was perhaps lead among, while at the same time saluting the machine they must work around. After all, what else could he do? By that point Welles had been rejected, for all intents and purposes, by Hollywood studio filmmaking. As early as his debut film Citizen Kane, he had been branded too solitary, too singular, too visionary. Too dangerous. He showed his face at the major studios only to take work as an actor for hire, a practice he engaged in order to financially support his independent directorial filmmaking efforts. As he affably put it in the speech, “in other words, I’m crazy.”

No other American filmmaker’s career has more divergence between the soaring peaks and desperate valleys than that of Orson Welles’. Don’t be fooled by his cultured, erudite persona – this global icon of cinema actually hails from humble Kenosha, the fourth largest city in Wisconsin. A child of privilege and declared wunderkind, the early part of his life was a steady ascension in the world of theater, then radio, and finally, movies. He hit the Hollywood scene with as much striking impact as it would come to hit him back with.

Welles was hired in his mid/twenties by RKO Radio Pictures with a then-unheard-of jealousy-inducing carte blanche deal to direct, produce, co-write and star in his debut film, Citizen Kane. With total artistic and creative control, Kane was triumphantly realized as the acute summation of all that cinema could be (and more), circa 1941. In the decades to come, Kane would be widely and not improperly recognized as the single greatest film ever made, indeed “the Citizen Kane of movie-making.” But this glory was short-lived. With the firebrand Kane, Welles managed to rub wrong both an all-powerful media mogul, one William Randolph Hearst, and his own studio, RKO. Never again would he have real control over any film.

The Welles of his later years in certain ways resembles a physically and professionally different person. In short, he struggled – and not just against his weight. (Although maybe, he didn’t bother struggling against that?) He struggled to get any movie made, reduced to living in friends houses, shooting films piecemeal over the course of years, always hustling for money and appearing regularly on TV talk shows to stay relevant. One might imagine that Welles might have thrived in today’s crowdfunding age, but, as the current disappointing tally on the campaign to fund the long-in-coming completion of his unassembled but fully filmed final work, The Other Side of the Wind shows, that may not be the case. Even today, it seems that Welles can’t get a film finished.

Orson Welles was an acknowledged genius and huckster, and demonstrated both qualities immaculately. If filmmaking is one big magic trick, Welles is the ultimate magician. He knew and demonstrated a love for the medium, a deep showman/artist’s authenticity in a way that only such a huckster could. As he said to the crowd on the night of his AFI honoring, to the Hollywood peers who had rejected him in the past and would reject him again, “My heart is full. With a full heart… I thank you.”

Orson Welles was an acknowledged genius and huckster, and demonstrated both qualities immaculately. If filmmaking is one big magic trick, Welles is the ultimate magician. He knew and demonstrated a love for the medium, a deep showman/artist’s authenticity in a way that only such a huckster could. As he said to the crowd on the night of his AFI honoring, to the Hollywood peers who had rejected him in the past and would reject him again, “My heart is full. With a full heart… I thank you.”

F for Fake

(1973, SACI, Dir. Orson Welles)

by Robert Hornak

I make this promise to you: I will tell you the truth about my first viewing of F for Fake for at least the remainder of this sentence. Before writing this, I almost gave in to the temptation to read more about the movie just to try and make heads or tails of it. Heads or tails. The phrase points to the trickery of a coin turning into a key in Welles’ hand in the opening moments, just as everything in the movie points to something else in the movie. It’s a confection of interlocking documentary storylines that progresses through a mirror-room of sometimes thoughtful revelation and sometimes cheap deceit. It’s Welles as low-budget Quixote, wielding his variously intricate and shallow mélange of vignettes against the true meaning of the real word FAKE and judging who most deserves the label, naming himself as a prime candidate. And it all plays like a flip fever dream Errol Morris might’ve had in childhood after a magic show and a bottle of Robitussin.

I spent the entire movie with the overwhelming feeling of being had. The movie itself feels fake – from the opening moments that are poorly, almost willfully, post-synched, to the limp application of by then shop-worn nouvelle vague editing techniques, to the very choice of subjects (an art forger, a faux biographer, their various hangers-on), all of whom tell their stories with the same sidelong twinkle as Welles at his most impish.

The entire thing drips with a kind of sophisticated sarcasm, pulling you into its joke even as it’s painting a target on your forehead. It’s impossible to tell while wading through the onslaught of seemingly random sound bites and images just what to take seriously, just what to pay attention to, and just who to believe at all. I became angry with myself because I’m told the movie is required viewing, but I was unable to fit it into any definition of “good” that I have in my critical arsenal. And then I hear the art forger Elmyr de Hory say twice in the movie, “If you forge a painting, and it hangs in an art gallery long enough, it becomes real.” And I can’t help but think F for Fake has simply hung in the gallery long enough to become revered. But – if you’ll permit me this confession – this isn’t the first time I’ve seen the movie. In fact, I’ve seen it many times before. Or have I? And I love it! Or do I? Maybe it’s required viewing, but it’s definitely an acquired taste. Then, I wouldn’t know. I’ve never seen it. Maybe.

Touch of Evil

(1958, Universal International Pictures, Dir. Orson Welles)

by Erik Yates

Touch of Evil finds Orson Welles as Hank Quinlan, a morally-questionable Police Capitan of a Texas border town where he is investigating the murder of 2 individuals following their brief visit into Mexico. Charleton Heston is a Mexican official on his honeymoon to a blonde American named Susan, played by Janet Leigh.

Filmed in a noir style in black and white, Welles directs and co-wrote the screenplay. Trading in the long, wide camera angles of his classic Citizen Kane, Welles here employs a drifting camera technique that allows the lens to float in an out of the scenes and up above the city where the crime is taking place, before settling back into the scene. The opening tracking shot of the two individuals leaving the small Mexican town to cross the border with knowing there is a bomb in their trunk, is effectively tense. Welles uses the weaving of the camera to provide different views of the town and the potential innocent victims that may be, if the bomb explodes, while carefully keeping the car with the bomb occasionally turning back into the scene.

Originally, the studio cut this opening tracking scene and made other editing choices against the wishes of Welles who fired off a 58 page plea of the editing changes he wanted. It wasn’t until the 1990’s that work began to make the changes he pleaded for in 1958. Eventually an extended version was released that restored Touch of Evil back to its intended form. This was the version I saw. Welles, transformed himself with a fat suit for the role and has great interaction with Heston, who was in his prime. Janet Leigh was a couple of years from her infamous scene in Psycho, and in Touch of Evilthere is even a small role for a young Dennis Weaver. This film was a very interesting look at the evil that lurks in the hearts of men, and the political corruption of the border towns at the time. While Citizen Kane will always be his masterpiece, Touch of Evil is a great look at the versatility of Welles both as an actor, and a director.

The Magnificent Ambersons

(1942, Mercury Productions, Dir. Orson Welles)

by Krystal Lyon

Orson Welles uses a beautiful opening prologue in The Magnificent Ambersons to give us a sense of the time in a small Midwest town, Indianapolis, before the creation of the automobile. Horse drawn carts wait for women, People aren’t quite so busy, and men prefer a derby hat to the traditional stovepipe. It’s Norman Rockwell idyllic, except for George Amberson Minafer, a wealthy, spoiled child that raises a ruckus wherever he goes. The prologue ends with, “There were people, grown people they were, who expressed themselves longingly. They did hope to live to see the day, when that boy would get his comeuppance. His what? His comeuppance! Something’s bound to take him down someday. I only want to be there to see it.” The drama sets forth and we watch as the Amberson family unravels and George learns some hard lessons and boy does he get his comeuppance!

So I don’t want to tell you much more of the story, I want you to see this film! It’s wonderful and I feel like a nimrod for not watching it sooner. It’s a wonderful adaptation from Booth Tarkington’s novel and it’s Welles second attempt at directing, producing and writing the screenplay. (In 1941, he made his directorial debut with Citizen Kane.) It was nominated for four Oscars and it’s Welles’ only other film, other than Citizen Kane, that was nominated for best picture. And while you do not see Welles in the film he is the magnificent narrator that leads you through the tale, which is a beautiful connection to his radio career. The dialogue is sharp and the acting is wonderful, Agnes Moorehead as Fanny Amberson and Tim Holt as George Amberson Minafer are phenomenal! And the cinematography is exquisite, after all this is Orson Welles! So… Why was The Magnificent Ambersons not the commercial success that Citizen Kane was the year before? (It lost over $800,000 in 1942!)

For me it came down to one facial expression in the final scene. Fanny Amberson has loved a man all her life and in the final scene you see her listening to that man talk about how he basically will always love someone else, and then Fanny smiles serenely. What? So, I have been in Fanny’s shoes and I never smile serenely when the dude I love starts talking about someone other than me! Something is wrong with that ending! So here’s the truth, Welles’ original ending, ended up on the editing floor and RKO reshot the ending with a happy spinster instead of an old maid wondering how she spent her life. It turns out RKO cut more than 40 minutes total from the film while Welles was in Brazil shooting another film. Welles was devastated by the edits and called them a “total betrayal”. The one original rough cut that was sent to Welles in Brazil is lost. We will never know the masterpiece that Welles created, and that makes me sad. The Magnificent Ambersons had all the potential to be that perfect film, like Citizen Kane, but RKO edited it down because of a test screening audience that left the theater sad. Well, with the film losing that much money, maybe George Amberson Minafer wasn’t the only one to get his comeuppance.

Jane Eyre

(1943, Twentieth Century-Fox, Dir. Robert Stevenson)

by Jim Tudor

Several birds were killed with one stone upon this viewing of Jane Eyre, least notable of them all is having finally seen the first major film to feature Orson Welles merely as an actor. Up until this point, admittedly only a couple of years into his movie career, Welles had been nothing short of a creative juggernaut, starting with his masterpiece Citizen Kane, and quickly branching out into other works that he would maintain varying degrees of control over. Jane Eyre was one such film, something that, despite his lack of screen credit, has his creative fingerprints all over it, from the straight-ahead production tempo to the intensely expresionist black & white visuals, to the casting of Agnes Moorehead in a supporting role, to the selection of frequent collaborator Bernard Hermann as its composer, to the presence of John Houseman as a screenplay collaborator (alongside Aldous Huxley and others). But at the end of the day, Robert Stevenson, the future Disney house director of Mary Poppins and The Love Bug, would assume directorial control of Twentieth Century-Fox’s prestige adaptation of the classic 1847 Charlotte Brontë novel.

Which brings me to my more glaring cultural omission up to this point. Prior to this viewing, my only familiarity with Jane Eyre, in any capacity, was the Val Lewton horror noir film I Walked A Zombie – a kind of “smuggled adaptation” coincidentally also released in 1943. As realized by Stevenson, this version is wildly impressive, as spellbindingly absorbing as any great classic film. Although it only runs a taut ninety-seven minutes, leaving a Brontë novice with the impression of a compressed narrative, this running time is not a wrong choice, as the film never drags.

Joan Fontaine stars the adult version of the title protagonist, a “plain woman” who spends her life drifting from one unfortunate circumstance to the next. Her one shot at true love seems an ill-advised longshot, as the sometimes charming, sometimes overbearing Mr. Rochester (a controversial performance by Welles) has a big skeleton in the closet. Or more accurately, the attic. By the time a funnel of wind whirls leaves around the embracing couple in an impressive wide shot late in the film, the gothic immesity of their shared world seems to be screaming back at them.

As in the novel (so I’m told), abuse cloaked in distorted Christianity is heaped upon Jane and the other girls of a strict boarding school as run by the horrendous man of the cloth, Brocklehurst (Henry Daniell). Made to carry irons in the rain as punishment for nominal infractions, a conequence that actually kills Jane’s only friend, played by an uncredited Elizabeth Taylor (!), one may go as far to observe that Bergman’s similarly suffering Fanny and Alexander never had it so bad.

There is nothing stuffy about 1943’s Jane Eyre, a must-see cinematic whirlwind of unforgetable gothic images, terrific performances, and thinly veiled wartime uncertainty.

The Third Man

(1949, London Film Productions, Dir. Carol Reed)

by Sharon Autenrieth

I don’t know why I was the only person who didn’t know that Orson Welles was only in The Third Manfor a few minutes, but apparently I was. When we decided to do this Welles tribute piece I remembered that my dad loved the music in The Third Man and figured it was time to see it for myself. As an example of Welles’ acting work, you might think this choice was a bit of a misfire – but Orson Welles could do a lot with a little. Few actors could match Welles’ ability to take command just by showing up on screen…but we’ll get to that in a minute.

The star of The Third Man – or at least the actor with the leading role – is Joseph Cotton, a frequent collaborator of Welles’ and a fine actor in his own right. Cotton plays Holly Martins, an American writer of pulp Westerns, broke and arriving in shattered and sectored post-war Vienna to take a job offer from his old friend, Harry Lyme. Unfortunately, he arrives at Lyme’s house to the news that Lyme has been killed in a car accident. The body has just been taken away, the porter tells him.

Harry Lyme is the focal point around which The Third Man revolves, the McGuffin that drives all that follows; and his mystique builds as Holly sets out to discover what really happened to Harry. Was it an accident? Was it murder? Was he the racketeer that the local authorities insist he was was, or was he the loyal, generous, “best friend I ever had” that Holly remembers?

The Third Man is a terrific film noir, filled with oily, duplicitous characters – all eager to assure Holly that Lyme’s death was a thoroughly accidental accident. British director Carol Reed keeps the viewer unsettled by combining luminous, black and white cinematography with bizarre tilts and monstrous shadows. And then there’s the music that my dad remembered: Anton Karas, a Viennese bistro musician, recorded 40 minutes of original zither music for the film and became a star.

Finally, there’s Harry Lyme himself, Orson Welles. His face appears in the shadows, late in the film – self-satisfied, amused, arrogant; undeniably charismatic. You see him, and you want to see more. His wry smile and sonorous voice make moral bankruptcy go down easy. After two world wars, in a devastated Europe, Harry seems to represent not so much cynicism as the new world order. The wonder is that The Third Man really is remembered for Orson Welles as much as for Joseph Cotton. How could such a small role be so iconic, and seem far bigger than the seconds on screen would suggest? Because it was Welles that played the part, and because Orson Welles was always more than the screen could contain.

The Muppet Movie

(1979, Henson Associates, Dir. James Frawley)

by Justin Mory

When I was in Kindergarten I believe I had a different Muppets T-Shirt for every day of the week, practically, so it is undoubtedly insane that I have, in fact, never seen the original The Muppet Movie. As this column is all about redressing grievously unseen movie classics by sitting down and actually watching them, and then typing up the results, when Orson Welles and the 100th anniversary of his birth popped up this May I decided the time had finally come to experience the cinematic delights of Kermit, Miss Piggy, Fozzie Bear and Company road-tripping across America in their initial adventure to fame and fortune, along with witnessing, possibly, The Greatest Cameo In Film History(???).

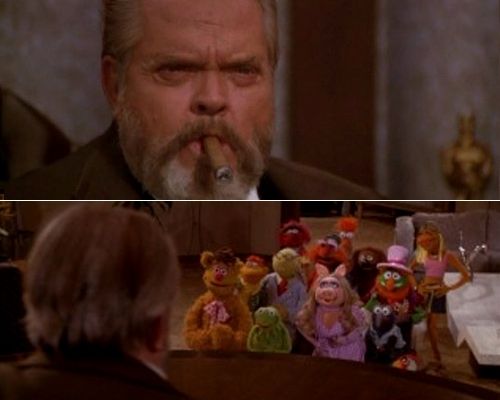

Well, maybe not… but The Muppets have always been about show-business and show-business folks, and from their groundbreaking 1976-81 TV series through their, to date, eight feature films, countless specials and omnipresent media appearances, they have interacted with everyone from Johnny Carson to John Denver. And as no one quite says “showbiz” as forcefully as Mr. Orson Welles, star of stage, airwaves, and screen, it is absolutely fitting that Welles, in about 3 minutes of screen time, should be the one to quite literally bestow “fame and riches” by offering the Muppet crew the “standard ‘Rich and Famous’ contract”!

As mega-producer “Lew Lord” Welles brings the full gravitas of his imposing screen presence —cowing poor Kermit behind his massive desk, girth, cigar, and late-career beard — to one spoken line, uttered in his best booming bass, but it is perhaps the most significant line of dialogue spoken in a Muppets movie. Precisely 40 years previous, in the summer of 1939, Orson Welles, after scaring the bejeezus out of an entire country with his legendary October 1938 broadcast of The War of the Worlds, was offered his own “Rich and Famous” contract by a producer at RKO studios named George Schaefer. The 24-year-old Welles would have unprecedented artistic and creative control over a project of his own choosing, the eventual result of which was the May 1st 1941 premiere, a few days shy of his 26thbirthday, of Citizen Kane, arguably The Greatest Movie Ever Made.

Is it tempting to assume that, on some level, the Muppets getting their first big break in their very first movie is in fact a recreation of when Orson Welles signed his Final Cut contract with RKO?

For me, yes!