An Historical Perspective

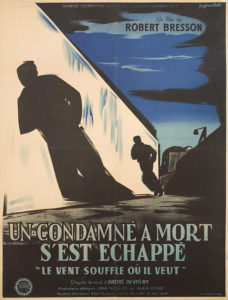

DIRECTOR: Robert Bresson/French/1956

The original trailer announcing the 1956 release of Robert Bresson’s fourth film, A Man Escaped, opens on shots of the Montluc Prison in Lyon, France with voiceover narration successively describing the physical geography of the prison – “walls, bars, soldiers, guns” – before resting on a memorial plaque which reads, “Here, under German occupation, 10,000 men suffered at the hands of the Nazis. 7,000 died.” All the while, off-screen, the sound of marching boots increases in volume, fairly overpowering the soundtrack, before giving way at its crescendo, the camera panning away from the plaque, to Mozart’s Kyrie theme from his Great Mass in C Minor. The effect, in three minutes of screen time, is one where the demonic gives way to the transcendent. Subtitled The Wind Bloweth Where it Listeth, Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped sets out to recreate the “truth”, as Bresson’s prologue informs us, “unadorned”, of Resistance fighter Lieutenant André Devigny’s (1916 – 1999) real-life escape from the Montluc Prison in 1943, as partly-fictionalized by Bresson in the story of the prisoner Fontaine (Francois Leterrier).

The original trailer announcing the 1956 release of Robert Bresson’s fourth film, A Man Escaped, opens on shots of the Montluc Prison in Lyon, France with voiceover narration successively describing the physical geography of the prison – “walls, bars, soldiers, guns” – before resting on a memorial plaque which reads, “Here, under German occupation, 10,000 men suffered at the hands of the Nazis. 7,000 died.” All the while, off-screen, the sound of marching boots increases in volume, fairly overpowering the soundtrack, before giving way at its crescendo, the camera panning away from the plaque, to Mozart’s Kyrie theme from his Great Mass in C Minor. The effect, in three minutes of screen time, is one where the demonic gives way to the transcendent. Subtitled The Wind Bloweth Where it Listeth, Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped sets out to recreate the “truth”, as Bresson’s prologue informs us, “unadorned”, of Resistance fighter Lieutenant André Devigny’s (1916 – 1999) real-life escape from the Montluc Prison in 1943, as partly-fictionalized by Bresson in the story of the prisoner Fontaine (Francois Leterrier).

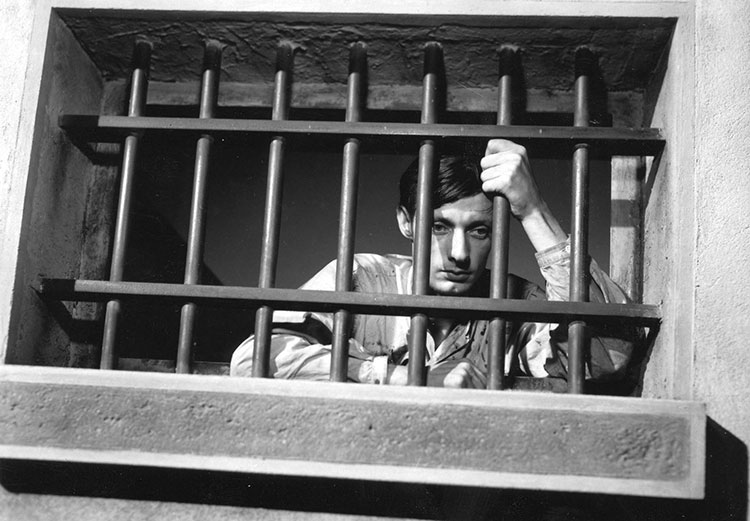

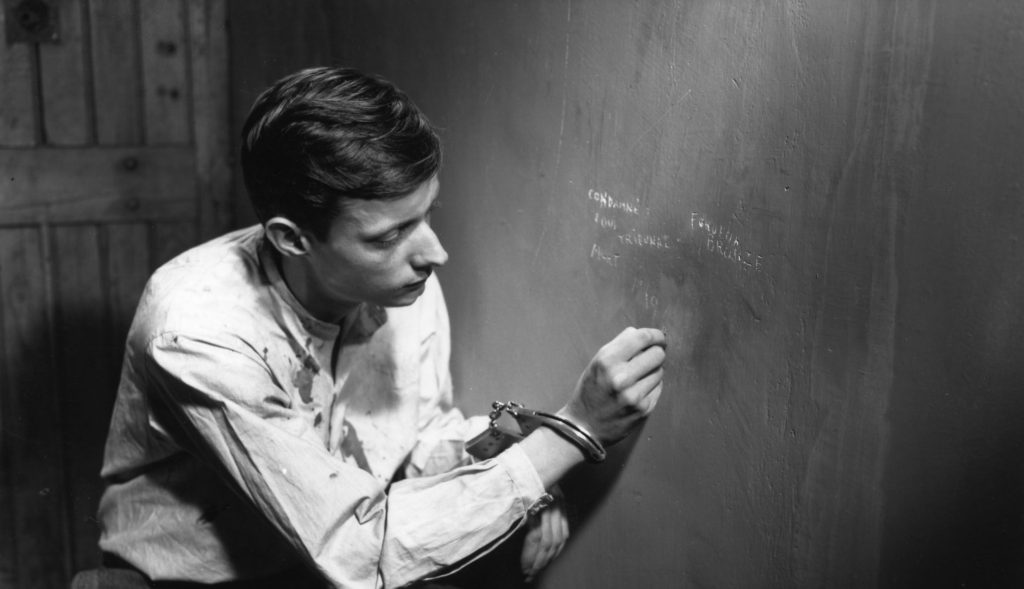

Through 99 of the most unlikely of riveting screen minutes a film viewer is ever likely to spend (period), we stay with Fontaine as he methodically plots his escape, attempts to communicate with other prisoners (both seen and unseen) through the walls of his cell, and, in the film’s most stirring moments – emphasized by the non-diegetic repetition of Mozart’s Great Mass – follow him daily to the prison courtyard where he empties his chamber pail and washes up in the common lavatory, his only moment of fellowship with his brothers-in-captivity. For a director whose style is one of deflating the artifice of drama with rigorously-observed shot composition and editing (a sidewise glance, a turn of a car door latch, the seized opportunity to flight outside the now-empty frame), along with non-expressive acting (we merely read singularity of purpose in Fontaine’s eyes, a reading which becomes more complex as the moral weight of events increase), the routine of solitary confinement and the passing of countless days in captivity become like mental (and spiritual) geography in the minds of its viewers – and all the more arresting for it.

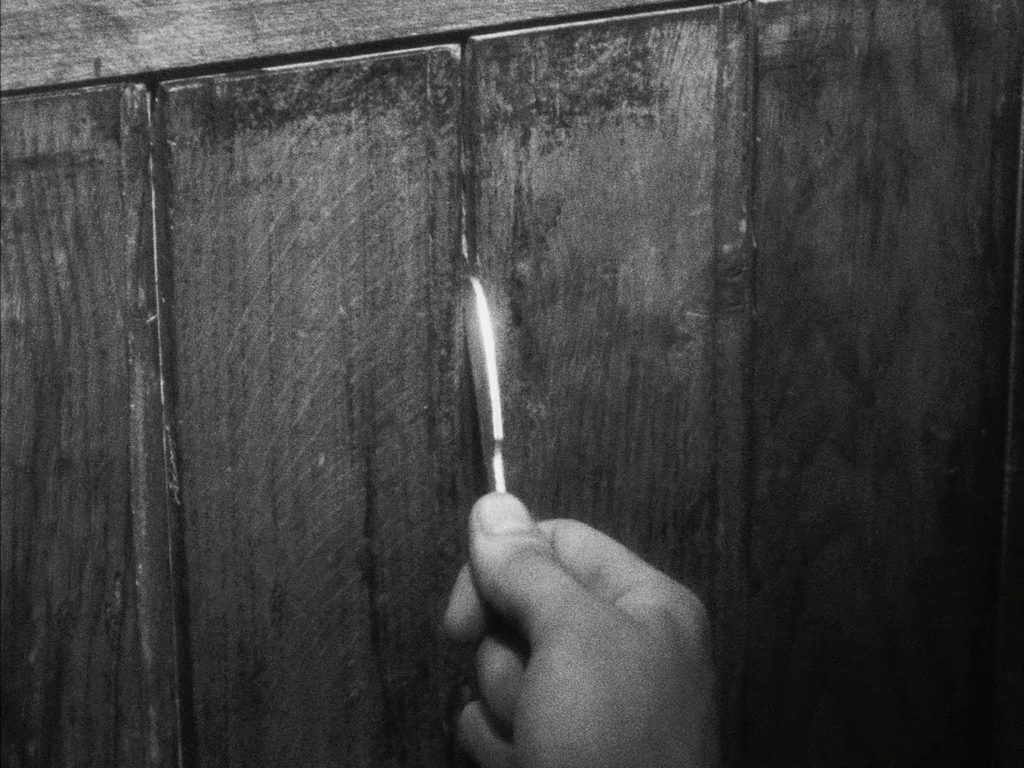

Drawing on Lt. Devigny’s factual memoirs, along with his own experience as a prisoner-of-war, Bresson’s matter-of-fact, deceptively simple style details in its exacting terms the experiences of one prisoner as a larger evocation of the tragedies and terrors of warfare. In a film where some of the most complex relationships are cultivated with “forbidden objects” such as a pencil, scraps of paper, a pin, the handle of a spoon, wood-shavings from the frame of his cell door, and horse-hair stuffing from his mattress, the stakes are as high and the drama, internal though it may be (marvelously elucidated in Fontaine’s diary-like voiceover narration), is as intense as a film depicting the landing at the Beach in Normandy.

Indeed, adding to the intensity following Fontaine being condemned to death at Lyon’s infamous Hotel Terminus – historically, the central command between 1942 and 1944 of SS Captain Klaus Barbie (1913 – 1991), notorious for cruelty and sadism even among Gestapo Officers – he suddenly gains a new cellmate in 16-year-old Jost (Charles Le Clainche) who, captured while wearing a German soldier’s coat, and later seen chatting blithely with a German officer, seems somewhat less than trustworthy. The drama gains a new dimension in this last third of the picture where Fontaine must decide whether to kill the boy, or to enlist his aid in escaping.

For us spoiler-concerned filmgoers of the early 21st century, where even the faintest hint of plot revealing apparently “ruins” our entire appreciation of the story, the climax and resolution of the drama is entirely given away by a more literal translation of the film’s original French title: condemned to die, the prisoner Fontaine escapes. But how he goes about doing so, the struggles and obstacles he must endure and overcome, and, most importantly, who he is brought to depend upon in order to effect his escape builds to a moment of quiet triumph unlike any yet captured on film. Screen poetry is achieved, as Bresson famously observed in his Notes on the Cinematographer (1950 – 1974), by “Empty[ing] the pond to get the fish”, and stripping away the battles and bullets down to the solitary efforts of one man in captivity, and subsequently the moral issue of whom he can trust, defines abstract qualities like “heroism” and “courage” in ways that a more conventional war movie could not hope to address.

François Leterrier in Robert Bresson’s A MAN ESCAPED (1956). Courtesy of Film Forum/Janus Films.

As a genre, the War Picture is occasionally guilty of sensationalizing war and trivializing the struggles of the men and women who fight it. As a somewhat personal prejudice against the genre – and do feel free to disagree – bombs and explosions and such for the sake of, yes, bombs and explosions and such tend to diminish the legacies of those who actually fought and actually died. As a memorial to the thousands of men and women who struggled and died, victims of the greatest evil of our time, A Man Escaped is a testament to the indomitable spirit of those who resisted it, as interpreted by some of the most rigorous, uncompromising, and poetic filmmaking of the 20th century.