Ridley Scott Ventures Into The Biblical Desert

DIRECTED BY RIDLEY SCOTT/2014

Who are these “Gods and Kings” in this movie, anyway? Being a lifelong churchgoer and student of the Bible, I can say with some confidence that I do not know. Although I confess I haven’t gone over it lately, I know the Exodus story, in which Moses is moved by God to lead the enslaved Israelites to freedom in the promised land. And yet, I don’t recognize this.

Who are these “Gods and Kings” in this movie, anyway? Being a lifelong churchgoer and student of the Bible, I can say with some confidence that I do not know. Although I confess I haven’t gone over it lately, I know the Exodus story, in which Moses is moved by God to lead the enslaved Israelites to freedom in the promised land. And yet, I don’t recognize this.

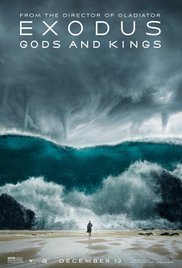

It’s time yet again for a remake of The Ten Commandments, and this time the honor goes to director and visualist extraordinaire, Ridley Scott (Gladiator, Alien). More accurately, it’s time for the latest cinematic adaptation of the Book of Exodus. In keeping with a Hollywood tradition that dates back to 1923, when Cecil B. DeMille committed the story to celluloid, the hero’s journey of Moses is once again rolled out for mass audiences in a spectacle showcasing the latest and greatest visual effects the movies have to offer. Why then should this be such a snooze?

Ridley Scott’s Old Testament is an overcooked 3D digital world that no actor seems particularly excited to be a part of.

The story is of course vital and essential, one that transcends religions and cultures. It’s that inherent quality that no doubt keeps creatives coming back to it. Yet in the end, these films, from both of DeMille’s to Dreamworks Animation’s satisfying if overburdened The Prince of Egypt, to this one, come down to “How will the Red Sea be parted this time?”

“Let my people go.: No? Okay, you ask for it…!”

Edgerton and Bale in EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS

Ridley Scott’s Old Testament is an overcooked 3D digital world that no actor seems particularly excited to be a part of. The plagues, each one rationally explained away as a thing of science and nature, fail to provoke. More likely, they arouse such questions as, “How many terabytes are we looking at here?”

Christian Bale’s Moses is an unengaged block of wood if there ever was one. Joel Edgerton’s Ramses is better, but awash in the staginess, expense, and faux-looseness of it all. (The characters are made to seem off-the-cuff and quippy in a failed way that surpasses any Star Wars prequel. At least those films don’t boast four separate screen writers like Exodus does.)

Bale goes in battle in EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS.

Exodus lands alongside of Darren Aronofsky’s Noah as the other big budget 2014 Hollywood studio adaptation of a familiar Old Testament story. Although both films have been targeted to the “faith based” demographic (as well as every other demographic they can be marketed to), they are both no less suspect in that department. And while the utter weirdness and high-wire crack-pottery of Noah makes for a far more interesting storytelling wrestling match for all parties involved, Exodus cannot stake much of a claim in this department. If anything, Exodus is downright confused with its own intentions.

Aronofsky gave us CGI rock transformers, but the presence of those beings in the film have proven to be one of a variety of meaty talking points that it has to offer. Scott, quite counterintuitively to the source material and the very text at the beginning of his film which assures audiences that through it all, God was with the Israelites, proceeds to literally explain away almost all things supernatural as acts of nature. As thanks for their level-headed wisdom, the paranoid Pharaoh has these expository advisors hung. Only the work of the Angel of Death (shown with effectively ominous simplicity) cannot be rationalized, but by that point, the film only seems to be playing against itself. When a grieving father asks what kind of God would do this, the film makes a point of there being no satisfying answer. What is meant to be a very hard lesson in obedience is instead a momentary dwelling on Holy terror.

When God appears to Moses in Exodus, it’s first as a blue-filtered burning bush (…that does indeed appear as though it’s being consumed by flame), then as a strident yet precocious young boy. He tells Moses to stand back and watch, and Moses then proceeds to spend the entire rest of the film doing just that.

While showcasing the God of the Old Testament as a young boy is certainly a fresh choice, it’s also indicative of how Scott and company read His historically recorded actions – as being on par with the kind of mass-scale chaos, violence and upheaval only a maniacal child would concoct and inflict, if only he could. Whereas the central horror of Scott’s recent sci-fi ooze-fest Prometheus could be said to be the realization that God is not there, the horror of Exodus might just be that He is – and all the world is his plaything.

Like I said, I don’t recognize this.

Bale’s Moses, although despite the historical assumption that he struggled with verbal problems, is as well spoken as Charlton Heston or any of the other movie Moses over the years have been. And yet, never does he get to utter the famous command “Let my people go!” Rather, the whole movie just sits there.