A Slightly Obsessed Halloween Special!

The days shorten, the shadows of night creep ever earlier, and the first chill is felt on the evening breeze. The leaves curl upon their branches, soon falling a duskshade rainbow of brown, orange, and deep red, as one’s thoughts, deepening and darkening with the season, turn naturally to… horror movies?

Well, friends, if you’re like me they do!

This Halloween I would like to invite you, fellow film fans, to accompany me on a journey of the imagination into TERROR! and GHOULISH DELIGHT! as we explore the roots, trivia, and fun miscellany of nearly 90 YEARS! of that grandest of all film genres, the horror movie!

So draw the curtains, dim the lights, draw a blanket around your shoulders, and draw a soothing, steaming draught of pumpkin spice latte as we embark upon 31 NIGHTS OF HALLOWEEN!

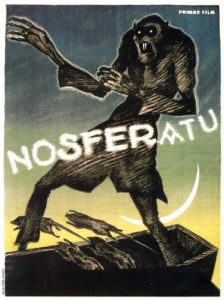

1st Night: NOSFERATU, A SYMPHONY OF HORROR

(1922, Germany, dir. F.W. Murnau)

The first ever screen Dracula, unofficially adapted from Bram Stoker’s classic novel, is also probably the finest. In this version, mainly because fledgling German film studio Prana could not secure the rights to the source material,“Dracula” becomes “Orlok,” “Harker” becomes “Hutter,” “Renfield” becomes “Knock,” and the settings of the novel are changed from Transylvania and London of the 1890’s to Slovakia and the town of Wisborg in 1838—even the word “nosferatu,” derived from similar legends of bloodthirsty ghosts in Central European folklore, is used in favor of “vampire”—but no screen adaptation of Dracula made since has matched this silent film for its shadowy compositions and dream-like air of dread. Max Schreck’s Count Orlok—pale, emaciated, with rodent-like teeth and long sharp talons for hands; more rat or spider than human—once seen, is not easily forgotten…

The first ever screen Dracula, unofficially adapted from Bram Stoker’s classic novel, is also probably the finest. In this version, mainly because fledgling German film studio Prana could not secure the rights to the source material,“Dracula” becomes “Orlok,” “Harker” becomes “Hutter,” “Renfield” becomes “Knock,” and the settings of the novel are changed from Transylvania and London of the 1890’s to Slovakia and the town of Wisborg in 1838—even the word “nosferatu,” derived from similar legends of bloodthirsty ghosts in Central European folklore, is used in favor of “vampire”—but no screen adaptation of Dracula made since has matched this silent film for its shadowy compositions and dream-like air of dread. Max Schreck’s Count Orlok—pale, emaciated, with rodent-like teeth and long sharp talons for hands; more rat or spider than human—once seen, is not easily forgotten…

Haunting Miscellany!

Two elements that substantially set apart director Murnau’s vision of horror from then-contemporary filmmaking—the postwar German film industry of the Weimar era—is his use of location space, both real and constructed, and lighting, both natural and artificial. Due to economic and technical restraints of the period, many films from that era—most famously The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1919—were comparably stagebound and static, with the camera moored to the ground, unmoving, for each individual shot or scene and with heavily-stylized stage space—copying the then-contemporary aesthetic distortions of Expressionism—standing in for real locations. Murnau broke with these traditions by finding no-less Expressionistic ‘opportunities’ in real-life locations: most notably, the gothic architecture of Orava Castle and medieval-like villages of Lübeck and Wismar.

But most of all, it’s Murnau’s collaboration with lighting cameraman Fritz Arno Wagner that so brilliantly found creative ‘expression’ in, say, the film’s most famous sequence where Count Orlok’s nightmarish shadow slowly creeps up Hutter’s staircase, oozes through Frau Hutter’s bedroom, rises up across her scantily-clad frame, and seizes her heart in its phantasmal pincer-grip!

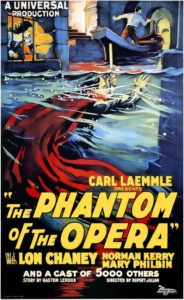

2nd Night: THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA

(1925, Universal, dir. Rupert Julian)

Lon Chaney’s signature role of “Erik the Phantom” takes center stage in this magnificent silent production, whose success served to inspire Universal Studio’s long series of horror movies in the early 1930’s. Lon Chaney went on to essay a whole slew of other “extreme characterizations” for a rival studio, MGM—where he played such roles as a cross-dressing ventriloquist (The Unholy Three, 1925), an armless knife-thrower (The Unknown, 1927), a paraplegic magician (West of Zanzibar, 1928), and various homicidal clowns (He Who Gets Slapped, 1924; Laugh, Clown, Laugh, 1928)—but this is the role for which he’ll always be remembered.

Lon Chaney’s signature role of “Erik the Phantom” takes center stage in this magnificent silent production, whose success served to inspire Universal Studio’s long series of horror movies in the early 1930’s. Lon Chaney went on to essay a whole slew of other “extreme characterizations” for a rival studio, MGM—where he played such roles as a cross-dressing ventriloquist (The Unholy Three, 1925), an armless knife-thrower (The Unknown, 1927), a paraplegic magician (West of Zanzibar, 1928), and various homicidal clowns (He Who Gets Slapped, 1924; Laugh, Clown, Laugh, 1928)—but this is the role for which he’ll always be remembered.

Haunting Miscellany!

Any case for silent horror movies being about ten times more creepy than their sound movie counterparts simply cannot be made without referencing the famous “reveal” by actress Mary Philbin, playing the object of the Phantom’s obsessions, Christine Daae, of the gross deformities lying under Lon Chaney’s mask. The suspense built around this moment is at such a fever pitch of melodramatic emotion that the audience could have very easily been disappointed had Chaney’s make-up not been up to the standard of his previous characterization for Universal, that of the Hunchback in the 1923 production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, but it’s that magical mixture of performance and chameleon-like appearance for which Chaney was so renowned, the look on his skull-like and deformed features suggests just as much pathos as it does fright, that makes the scene so terrifying—and even touching.

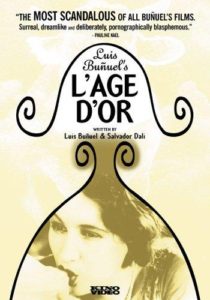

3rd Night: L’AGE D’OR

(1930, France, dir. Luis Buñuel)

A Surrealist art film may seem an odd choice on a list of Halloween-themed movies, but director Buñuel’s savage attack on the manners and mores of high society—and, especially, organized religion—is (or ‘was’, at least) as shocking and outrageous as any horror movie. The avant-garde, by its very definition, has always raised the bar for that which follows, and it’s interesting to note how genre filmmaking, especially the horror genre, assimilated its transgressing (and transgressive) techniques. And I know that might possibly sound boring, but any movie that features a guy randomly kicking a small dog AND knocking over a blind guy AND throwing a full-regalia Catholic Cardinal out the window can’t be all bad!

A Surrealist art film may seem an odd choice on a list of Halloween-themed movies, but director Buñuel’s savage attack on the manners and mores of high society—and, especially, organized religion—is (or ‘was’, at least) as shocking and outrageous as any horror movie. The avant-garde, by its very definition, has always raised the bar for that which follows, and it’s interesting to note how genre filmmaking, especially the horror genre, assimilated its transgressing (and transgressive) techniques. And I know that might possibly sound boring, but any movie that features a guy randomly kicking a small dog AND knocking over a blind guy AND throwing a full-regalia Catholic Cardinal out the window can’t be all bad!

Haunting Miscellany!

The outrage with which this film was greeted, a mere 4 days after its premiere at Studio 28 in Paris on November 29, 1930, resulted not only in property damage and assault—a militant right-wing group threw ink at the screen and physically attacked members of the audience—but also priceless works of Surrealist art by Dalí (the film’s credited co-writer), Man Ray, Miró and others being slashed, stomped upon, and set fire to! The upshot of this brouhaha was the film was immediately yanked from distribution and subsequently banned. The film would not be exhibited publicly again for another 30 years, during which time Spanish-born filmmaker Buñuel spent most of the intervening period as a low-budget filmmaker in Mexico.

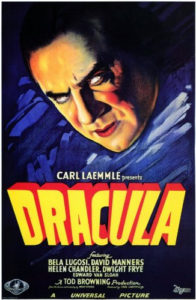

4th Night: DRACULA

(1931, Universal, dir. Tod Browning)

Bela Lugosi IS “Count Dracula” in the film that officially kick-started Universal’s famous series of horror movies. Director Tod Browning’s and producer Carl Laemmle, Jr.’s original choice for the title role had been none other than Browning’s old colleague at MGM, Lon Chaney—between whom had been one of the most famous screen partnerships of all time, and who had previously directed Chaney as a (fake) vampire in the (now lost) 1928 production of London After Midnight—but Chaney’s untimely death from lung cancer in August 1930 forced them to find another suitable candidate for whom “the blood is the life”! Released on Valentine’s Day 1931, the magnetic performance of a 48-year-old Hungarian émigré, suggesting the mountainous wastes and untamed wilderness of ancient Transylvania in every v-accented utterance, was widely reported as having sent the (mainly) female portion of its audiences into “fainting spells” and “paroxysms of erotic delight”. (Seriously!)

Bela Lugosi IS “Count Dracula” in the film that officially kick-started Universal’s famous series of horror movies. Director Tod Browning’s and producer Carl Laemmle, Jr.’s original choice for the title role had been none other than Browning’s old colleague at MGM, Lon Chaney—between whom had been one of the most famous screen partnerships of all time, and who had previously directed Chaney as a (fake) vampire in the (now lost) 1928 production of London After Midnight—but Chaney’s untimely death from lung cancer in August 1930 forced them to find another suitable candidate for whom “the blood is the life”! Released on Valentine’s Day 1931, the magnetic performance of a 48-year-old Hungarian émigré, suggesting the mountainous wastes and untamed wilderness of ancient Transylvania in every v-accented utterance, was widely reported as having sent the (mainly) female portion of its audiences into “fainting spells” and “paroxysms of erotic delight”. (Seriously!)

Haunting Miscellany!

OK, I’m gonna go out on a limb here and say… NOT as great a movie as its reputation might suggest. The first 25 minutes or so—on the Vorgo Pass, in Dracula’s Castle, and aboard the ‘good ship’ Demeter—ARE truly atmospheric and eerie… which, unfortunately, only serves to make the next 45 minutes so disappointing. Edward Van Sloan’s stalwart Van Helsing and Dwight Frye’s hysterically insane Renfield aside, boring second leads and endlessly talky scenes (unimaginatively shot in indifferently-designed drawing rooms) nearly sink the last 2/3rds of the movie. The film DOES end on a high-note, with lots of action up and down the winding steps of Charles D. Hall’s magnificent Carfax Abbey set, but the real reason this movie is a must-see is LUGOSI! himself, whose old-world charm and otherworldly charisma make him the ultimate Hollywood screen vampire.

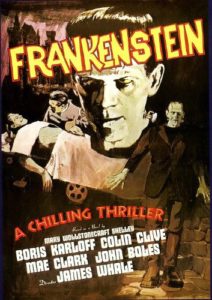

5th Night: FRANKENSTEIN

(1931, Universal, dir. James Whale)

Following a “friendly word of warning” from actor Edward Van Sloan—playing Dr. Waldman—the film opens with the good doctor (Colin Clive) and his hunchback assistant (Dwight Frye) digging up a corpse at the local cemetery (“He’s just resting – waiting for new life to come!”), and, subsequently, cutting down a recently-executed man from the gallows… and we’re off! Director James Whale, in his first horror movie, refashioned the articulate, agile creature of Mary Shelley’s classic into a mute, stumbling monster… and THAT’S what people remember whenever anyone mentions “Frankenstein.” Whale and makeup artist Jack Pierce’s iconic design for “The Monster”—with its flat and angled head, neck bolts, and scars—is still scary, but it took the soulful performance of an actor originally billed as “?” (Boris Karloff) to suggest a glimmer of humanity behind the brutality and ugliness. From its ghoulish opening scene to its famous burning windmill climax, this early sound classic remains just as creepy and terrifying as when it premiered 82 year ago!

Following a “friendly word of warning” from actor Edward Van Sloan—playing Dr. Waldman—the film opens with the good doctor (Colin Clive) and his hunchback assistant (Dwight Frye) digging up a corpse at the local cemetery (“He’s just resting – waiting for new life to come!”), and, subsequently, cutting down a recently-executed man from the gallows… and we’re off! Director James Whale, in his first horror movie, refashioned the articulate, agile creature of Mary Shelley’s classic into a mute, stumbling monster… and THAT’S what people remember whenever anyone mentions “Frankenstein.” Whale and makeup artist Jack Pierce’s iconic design for “The Monster”—with its flat and angled head, neck bolts, and scars—is still scary, but it took the soulful performance of an actor originally billed as “?” (Boris Karloff) to suggest a glimmer of humanity behind the brutality and ugliness. From its ghoulish opening scene to its famous burning windmill climax, this early sound classic remains just as creepy and terrifying as when it premiered 82 year ago!

Haunting Miscellany!

I think there’s no better way to describe the legacy of this film than to mention a 1973 Spanish movie called The Spirit of the Beehive (dir. Victor Erice). Spirit is set at the end of the Spanish Civil War and concerns a 6-year-old girl who sees Frankenstein for the first time when a traveling carnival organizes a makeshift showing of the film in her small village. Frightened by the movie (especially a scene where the monster accidentally kills a little girl—a scene which has frequently been excised from many existing prints of the original film), she becomes obsessed with the monster character, who dominates her dreams and imaginings over the next weeks, even becoming a sort of ‘imaginary friend’… and to reveal more would be a disservice. I can’t think of many better screen portrayals of childhood—how a kid actually thinks and feels—and, especially, how kids interpret what they see up on the big screen. It’s a unique and poetic film, which should be better known, that is a testament to Frankenstein‘s place in the popular imagination.

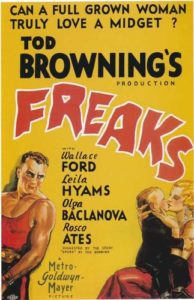

6th Night: FREAKS

(1932, MGM, dir. Tod Browning)

More than 80 years after its initial (limited) release, Dracula director Tod Browning’s tale of a troupe of circus sideshow “freaks” and their violent revenge on two “normal”-bodied tormentors is still one of the most controversial horror movies ever made. From performers billed as “The Living Torso” (Prince Randian), “Half Boy” (Johnny Eck), and, collectively, “The Pinheads” (Eliva and Jenny Lee Snow; and two other uncredited performers with the neurodevelopmental disorder, microcephaly), Freak‘s deep cast of real-life sideshow artists, along with material thematically championing inner beauty over deformity of character (“Gooba-gobble! Gooba-gobble! We accept her! One of us!”), proved a bit strong for Depression-era audiences expecting “monsters” to be portrayed as inherently evil. Censors cut the film by a half-hour… and eventually banned it altogether. The film found new life after being rediscovered—and heralded as a ‘cult classic’—in the late 60’s. Celebrated today for its unique atmosphere and rather progressive, and even celebratory, view of “differently-abled” people, Freaks is one of the few films from this era that succeeds today precisely because it was so roundly rejected when it was made!

More than 80 years after its initial (limited) release, Dracula director Tod Browning’s tale of a troupe of circus sideshow “freaks” and their violent revenge on two “normal”-bodied tormentors is still one of the most controversial horror movies ever made. From performers billed as “The Living Torso” (Prince Randian), “Half Boy” (Johnny Eck), and, collectively, “The Pinheads” (Eliva and Jenny Lee Snow; and two other uncredited performers with the neurodevelopmental disorder, microcephaly), Freak‘s deep cast of real-life sideshow artists, along with material thematically championing inner beauty over deformity of character (“Gooba-gobble! Gooba-gobble! We accept her! One of us!”), proved a bit strong for Depression-era audiences expecting “monsters” to be portrayed as inherently evil. Censors cut the film by a half-hour… and eventually banned it altogether. The film found new life after being rediscovered—and heralded as a ‘cult classic’—in the late 60’s. Celebrated today for its unique atmosphere and rather progressive, and even celebratory, view of “differently-abled” people, Freaks is one of the few films from this era that succeeds today precisely because it was so roundly rejected when it was made!

Haunting Miscellany!

A deeply personal project for director Browning, who in his youth had literally run away from home and joined the circus, it was also the film that effectively ended his career in Hollywood. Though, appropriate for the director of Dracula, he’d “rise” again for at least two more moderate successes at MGM in the mid-30’s (Mark of the Vampire and The Devil-Doll), Browning, the director of horror legend Lon Chaney’s greatest roles (The Unholy Three, West of Zanzibar, London After Midnight, etc.) spent the rest of his life (he lived until 1962) in comparative obscurity to the renown he once enjoyed. With Freaks, Browning’s documentary-like dedication to honestly portraying the “inner lives” of the sideshow performers—Prince Ramadian, “The Living Torso”’s ability to light a cigarette without hands or legs, Johnny Eck, “The Half Boy”’s astonishing feats of gymnastic ability without the lower part of his body; even social and married life(!) for the two very temperamentally-different sisters, “The Siamese Twins” Daisy and Violet Hilton—proves the film, along with Browning’s vision, was entirely non-exploitative and, indeed, years ahead of its time.

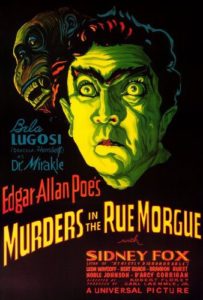

7th Night: MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

(1932, Universal, dir. Robert Florey)

About all this movie has in common with the Poe story, besides the title, is the identity of the ‘murderer.’ Otherwise, the film’s story—and broadly expressionistic set-design—seems mainly to have been inspired by the post-WWI German classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919)… with ‘murdering ape’ substituting for ‘murdering sleep-walker.’ Bela Lugosi plays a carnival barker/biologist called “Dr. Mirakle” who, in 1840’s France, sets out to prove his evolutionary theories by kidnapping prostitutes and injecting them with the blood of his caged ape. The film is also noted for a particularly violent abduction scene that (vaguely) suggests interspecies, um, “improprieties.” Pretty strong stuff—especially for a classic Hollywood studio film. (Though, in many shots, the obvious ‘guy in an ape suit’ does tend to be distracting for modern audiences – but, for the right sort of audience today, should actually prove a good deal of the fun!)

About all this movie has in common with the Poe story, besides the title, is the identity of the ‘murderer.’ Otherwise, the film’s story—and broadly expressionistic set-design—seems mainly to have been inspired by the post-WWI German classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919)… with ‘murdering ape’ substituting for ‘murdering sleep-walker.’ Bela Lugosi plays a carnival barker/biologist called “Dr. Mirakle” who, in 1840’s France, sets out to prove his evolutionary theories by kidnapping prostitutes and injecting them with the blood of his caged ape. The film is also noted for a particularly violent abduction scene that (vaguely) suggests interspecies, um, “improprieties.” Pretty strong stuff—especially for a classic Hollywood studio film. (Though, in many shots, the obvious ‘guy in an ape suit’ does tend to be distracting for modern audiences – but, for the right sort of audience today, should actually prove a good deal of the fun!)

Haunting Miscellany!

Horror aficionados are undoubtedly aware that Lugosi and director Robert Florey were the first star/director team assigned to Frankenstein and, indeed, that test footage and promotional material was shot depicting the legendary Hungarian horror star in full dress and make-up in the role that later went to his rival at Universal, Boris Karloff. Comparing this movie to the sterling example of Hollywood horror that became the James Whale and Boris Karloff Frankenstein undoubtedly proves that the producers at Universal made the right choice for their director and star with their stronger property, reassigning Lugosi and Florey to the less-prominent Murders, but has still done little to stifle speculation as to what a Lugosi Frankenstein might have been like. Lugosi eventually did play The Monster, opposite Lon Chaney, Jr. in 1943’s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, but the Florey/Lugosi Murders in the Rue Morgue remains a worthy and atmospheric effort for Universal Studios in their horror movie-making prime.

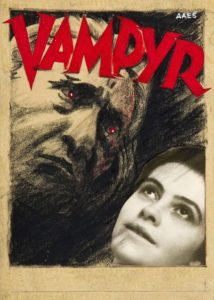

8th Night: VAMPYR

(1932, Germany/France, dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer)

The great Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s follow-up to his monumental silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), suffered in comparison during its original release, but has been reevaluated since as a worthy successor to his earlier masterpiece. Where Passion took as its subject the persecution and martyrdom of a saint, the deeply spiritual filmmaker here explores the corruption of the soul and, through extension, the contagion of evil—but, y’know, with vampires and stuff. Along with F.W. Murnau in Nosferatu, Dreyer creates an atmosphere of old-world superstition and dread, complete with frighteningly-realistic explanatory “text” interspersed throughout—included in both films’ handy, Gothic-font Vampire Guide books—that makes for perfect late-night viewing. Adapted from J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1871 short novel, Carmilla (pre-dating Bram Stoker’s Dracula by almost 3 decades), and best viewed, perhaps, between the hours of one and three in the morning, Dreyer’s film is truly unique for its dream-like atmosphere, which evokes a shadowy nether world between nightmare and waking. (Personally, I think the film’s long-shot, tracking view from inside a coffin, courtesy of legendary lighting cameraman Rudolph Maté, is possibly the most terrifying image, and sequence, ever committed to film.) A one-of-a-kind masterpiece.

The great Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s follow-up to his monumental silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), suffered in comparison during its original release, but has been reevaluated since as a worthy successor to his earlier masterpiece. Where Passion took as its subject the persecution and martyrdom of a saint, the deeply spiritual filmmaker here explores the corruption of the soul and, through extension, the contagion of evil—but, y’know, with vampires and stuff. Along with F.W. Murnau in Nosferatu, Dreyer creates an atmosphere of old-world superstition and dread, complete with frighteningly-realistic explanatory “text” interspersed throughout—included in both films’ handy, Gothic-font Vampire Guide books—that makes for perfect late-night viewing. Adapted from J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1871 short novel, Carmilla (pre-dating Bram Stoker’s Dracula by almost 3 decades), and best viewed, perhaps, between the hours of one and three in the morning, Dreyer’s film is truly unique for its dream-like atmosphere, which evokes a shadowy nether world between nightmare and waking. (Personally, I think the film’s long-shot, tracking view from inside a coffin, courtesy of legendary lighting cameraman Rudolph Maté, is possibly the most terrifying image, and sequence, ever committed to film.) A one-of-a-kind masterpiece.

Haunting Miscellany!

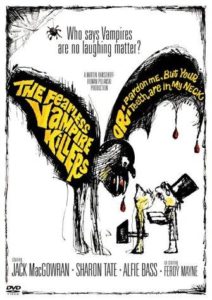

As I have just one more film about vampires planned for this list (and it’ll be a comedy) I’d like to briefly make a point here about what a vampire SHOULD be… their being so popular these days and all. In films like Nosferatu, Dracula, and Vampyr, vampires are much more than mere monsters, and their presence suggest actual themes (you’ve heard of those?) like spiritual degeneration, pestilence, eternal damnation… and so on. Though the observation is at least three years out of date by now, I believe that true horror fans should continue, steadfastly, to maintain that vacant, hollow-eyed pretty boys (and girls) ‘emoting’ through soap-level melodramatics should NEVER a true vampire tale make.

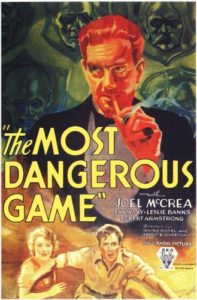

9th Night: THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME

(1932, RKO, dir.(s) Ernest B. Schoedsack & Irving Pichel)

Based on Robert Connell’s short story of the same name—which is about a Russian count who lures shipwrecked travelers to his remote island paradise and then hunts them for sport—this is another pretty potent Pre-Code* movie with a lotta sex and a lotta violence (for its day, at least). A scene where Leslie Banks (as “Count Zaroff”) coolly enjoys a cigarette while contemplating “further actions” towards the virginal heroine (Fay Wray), or when the unwary travelers enter the Count’s “trophy room” and encounter a human head mounted to the wall, or another scene where the hero (played by a young Joel McCrea) breaks an assailant’s back over his own (you actually hear it CRACK!) are all still fairly shocking. Producers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack made this movie concurrent to their BIG production of King Kong (1933) and, in addition to casting two actors from that film (Fay Wray & Robert Armstrong), also shot it on the ‘big ape’ movie’s famed jungle sets. From the shipwreck in shark-infested waters that opens the film to the Count being torn apart by his pack of wild dogs at its climax, this is classic Hollywood at its most grisly and extreme.

Based on Robert Connell’s short story of the same name—which is about a Russian count who lures shipwrecked travelers to his remote island paradise and then hunts them for sport—this is another pretty potent Pre-Code* movie with a lotta sex and a lotta violence (for its day, at least). A scene where Leslie Banks (as “Count Zaroff”) coolly enjoys a cigarette while contemplating “further actions” towards the virginal heroine (Fay Wray), or when the unwary travelers enter the Count’s “trophy room” and encounter a human head mounted to the wall, or another scene where the hero (played by a young Joel McCrea) breaks an assailant’s back over his own (you actually hear it CRACK!) are all still fairly shocking. Producers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack made this movie concurrent to their BIG production of King Kong (1933) and, in addition to casting two actors from that film (Fay Wray & Robert Armstrong), also shot it on the ‘big ape’ movie’s famed jungle sets. From the shipwreck in shark-infested waters that opens the film to the Count being torn apart by his pack of wild dogs at its climax, this is classic Hollywood at its most grisly and extreme.

Haunting Miscellany!

Released in the latter third of 1932, Game comes at the forefront of a group of violent melodramas set in exotic locales, which also includes Paramount’s Island of Lost Souls and MGM’s Kongo, that effortlessly transgressed the then-acceptable boundaries of ‘decorum and restraint’ with some good ol’ fashioned sadism and frank sexuality! Referencing the ‘*’ above, the Pre-Code era in Hollywood refers to the period prior to 1934 when the Motion Picture Production Code, drafted in 1930, had yet to take full effect. As such, studios and filmmakers alike had a much freer hand during this period to have a character actually say a line like, “Kill, then love! When you have know that you have known ecstasy.” and then proceed to have that same character immediately act upon that intention! The murderous lechery of a character like Count Zaroff may have been almost impossible to portray a scant year and a half after the release of this film, but the ‘dance’ around the Production Code that filmmakers engaged in after its industry-wide adoption—“putting one past the Hays Office”—also made for some no-less interesting choices when violence and sexuality could merely be suggested.

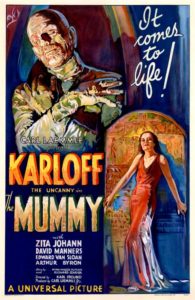

10th Night: THE MUMMY

(1932, Universal, dir. Karl Freund)

After “Dracula” and “Frankenstein’s Monster”, Karloff’s “Imhotep, The Mummy” is frequently singled-out among Universal Studio’s great monster creations. Edward Van Sloan, following his roles in Draculaand Frankenstein, once again plays the aging professor/doctor character (this one is named “Muller”) in dogged, unflappable pursuit of an unknown, unholy terror—this time beneath the ancient sands of Egypt!

After “Dracula” and “Frankenstein’s Monster”, Karloff’s “Imhotep, The Mummy” is frequently singled-out among Universal Studio’s great monster creations. Edward Van Sloan, following his roles in Draculaand Frankenstein, once again plays the aging professor/doctor character (this one is named “Muller”) in dogged, unflappable pursuit of an unknown, unholy terror—this time beneath the ancient sands of Egypt!

As the reincarnated object of The Mummy’s desire, the entrancing and otherworldly Zita Johann makes quite the impression in the type of role, the stereotypical “woman in peril,” that usually makes no impression at all; here actually justifying The Mummy’s own dogged, unflappable pursuit of his beloved (in the film’s famed “mirror of time” flashback sequence to Ancient Eqypt) across 4,000 years of human history. Makeup genius Jack Pierce out-did himself with his strongly textured mummy design—whose wraps, bandages, and 4000 yr. old dusty/flaking ‘skin’ (like desert sand crumbling under the hot Egyptian sun!) set a standard for all future screen mummies.

As the first Universal horror property not based on an established literary classic, as was the case with Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, The Mummy has nonetheless proved singularly, and appropriately, deathless; inspiring four sequels, a late 40’s de rigueur Abbott & Costello “encounter,” a four-film Hammer series in the 60’s, and, of course, the latter-day action/adventure special-effects extravaganzas.

Haunting Miscellany!

Director Karl Freund, the German cameraman of such classics as F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924) and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), was instrumental in establishing the unique look and feel for many of these early 30’s Universal classics and, indeed, as the film’s credited cinematographer, had practically taken over production on the previous year’s Dracula when the film’s credited director, Tod Browning, suffered a mysterious “infirmity” (possibly crippling depression) mid-way through production. “German Expressionism” is perhaps an overused, and often misapplied, critical, um, ‘expression’ used to describe the shadowy lighting style and jutting, jagged-edged set design of these early horror movies, but, in the case of those produced at Universal between 1931 – 1935, the term is actually quite justified.

Not only did Universal directors like James Whale and cameramen like Arthur Edeson take specific visual cues from the films of F.W. Murnau, Paul Leni, Fritz Lang et al., but the thematic treatment of insanity, as a metaphor for human contact with the Unknown, is as equally well-represented in their Hollywood counterparts as when, most famously, the entire narrative for 1919’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is revealed ::SPOILER!:: to be the fantasy of a madman.

Here, it’s a young actor named Bramwell Fletcher, playing archeology assistant “Ralph Norton,” who, reading an incantation from an ancient scroll, unwarily awakens The Mummy from its ageless sleep of death and lets loose with perhaps the most blood-curdling laugh of madness in film history when a dust-covered, shroud-wrapped palm is placed on his shoulder! As with their Expressionistic forbears, style and narrative collide here to create a moment of truly pulse-pounding terror.

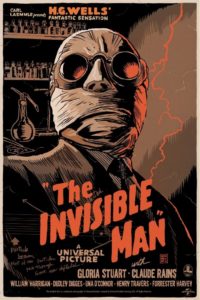

11th Night: THE INVISIBLE MAN

(1933, Universal, dir. James Whale)

Director Whale’s third horror movie is a reasonably close adaptation of the H.G. Wells science-fiction novel, refashioned (slightly) as a ‘tale of the macabre.’ Whale’s trademark mixture of humor and horror finds its most black, for the former, and disturbing, for the latter, iteration as a once dedicated and driven scientist is transformed into a cackling, megalomaniacal monster by the, um, ‘hidden’ side-effects of invisibility.

Director Whale’s third horror movie is a reasonably close adaptation of the H.G. Wells science-fiction novel, refashioned (slightly) as a ‘tale of the macabre.’ Whale’s trademark mixture of humor and horror finds its most black, for the former, and disturbing, for the latter, iteration as a once dedicated and driven scientist is transformed into a cackling, megalomaniacal monster by the, um, ‘hidden’ side-effects of invisibility.

In perhaps the most distinctive debut in film history, the great Claude Rains ‘appears’ as the disembodied voice, wrapped in surgical bandages… and MAD! MAD! MAD! Scenes set in contemporary English country inns, rural police stations and small village squares are particularly striking in contrast to other more exotic or ‘mythic’ horror films of the period—AND authentic: Whale came from a working-class English background and infused the film with a sharp sense of time and place.

Of particular note is the film’s visual effects—courtesy of matte processing and precision-timed wires—that give the ‘illusion,’ or its lack, of a one-man force of total destruction and chaos… Indeed, a kill-crazy rampage that ends with the vengeance-driven deaths of a colleague, several police officers, and an entire load of passengers (aboard a derailed train), this might very well be the highest body count of any horror movie to this point in cinematic history!

Haunting Miscellany!

This was cinematographer Arthur Edeson’s third and final collaboration with director Whale, following Frankenstein in 1931 and The Old Dark House in 1932. It seems appropriate that Edeson should have worked on ¾ of Whale’s four film-contribution to the horror genre, not only establishing the shadowy compositions and bold framing of Whale’s signature visual style, but also creating the unique atmosphere that supported the larger-than-life (or ‘death,’ for that matter) characterizations of actors like Colin Clive, Boris Karloff, and Claude Rains.

(Indeed, if you should ever catch their previous collaboration, the literally dripping-with-atmosphere Grand Guignol thriller, The Old Dark House— which I would highly suggest—the success of that film is entirely supported by its bewildering succession of grotesques, each more bizarre than the last!)

Edeson, whose career stretched back to the mid-1910’s, moved on to MGM and, eventually, Warner Brothers where he achieved a career high photographing, in succession, The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942), and Across the Pacific (1942), providing a clear stylistic link between horror films of the 1930’s and the wartime melodramas and (nascent) film noir of the 1940’s.

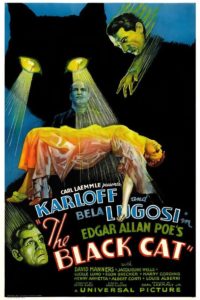

12th Night: THE BLACK CAT

(1934, Universal, dir. Edgar G. Ulmer)

“Suggested by the immortal Edgar Allan Poe classic,” this is another adaptation of Poe that has little (or, in this case, absolutely nothing) to do with Poe, but is rather the first big screen team-up of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff—who play a ailurophobic (that’s a ‘fear of cats’ to you, bub) psychiatrist and devil-worshipping architect, respectively—facing-off in classic Hollywood’s most undoubtedly macabre (and explicit) ‘game of death.’ The specter of the first World War hangs heavily over this Baroque and heavily-stylized production, with “Engineer Poelzig” (Karloff) and “Dr. Werdegast” (Lugosi) waging battle once more, after an 18-year interval, on the site of a notorious battlefield upon which the evil architect has erected a magnificent Art Deco temple to Satan!

“Suggested by the immortal Edgar Allan Poe classic,” this is another adaptation of Poe that has little (or, in this case, absolutely nothing) to do with Poe, but is rather the first big screen team-up of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff—who play a ailurophobic (that’s a ‘fear of cats’ to you, bub) psychiatrist and devil-worshipping architect, respectively—facing-off in classic Hollywood’s most undoubtedly macabre (and explicit) ‘game of death.’ The specter of the first World War hangs heavily over this Baroque and heavily-stylized production, with “Engineer Poelzig” (Karloff) and “Dr. Werdegast” (Lugosi) waging battle once more, after an 18-year interval, on the site of a notorious battlefield upon which the evil architect has erected a magnificent Art Deco temple to Satan!

Director Ulmer’s fluid direction is full of bravura ‘director moments;’ which include a low angle of Karloff gazing at his (pure) object of (impure) desire, and then rack-focusing to a nude statue held in his (foul) clutches; flamboyant blocking/camerawork, as when the camera pans 360 degrees around Karloff’s basement lair (filled with glass displays preserving the corpses of his former lovers!) while he delivers his notable “living dead” monologue; and (then-)innovative use of classical music, enhancing both mood and theme with selections from Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Mendelssohn. In total, Ulmer’s bracing style serves to elevate these melodramatic goings-on to the level of opera. If any horror or genre picture from this period deserves to be called a masterpiece, this may be it!

Haunting Miscellany!

Regarding “no-less interesting [writing/directorial] choices when violence and sexuality could merely be suggested,” Ulmer’s The Black Cat, which at various points in its wildly disturbing narrative suggests such thematic elements as sadism, necrophilia, devil worship, genocide, and (implied) incest, undoubtedly begs the question: how could this movie ever have been made after the advent of the Production Code in January 1934? (In other words, how in heck did they get away with it?)

Released 5 months after the Production Code was in full swing, one might assume that nascent Hollywood director Edgar G. Ulmer and screenwriter “Peter Ruric” (a pseudonym for the hard-boiled mystery writer, Paul Cain) are “dressing up” the lurid atmosphere with high culture, pop psychology, and thematic elements relating to war and its legacy to the point where Joseph I. Breen and the boys at the Hays Office (again, more shorthand for screen censorship) musta simply overlooked, or simply slept through, say, Karloff’s clearly predatory relationship with Lugosi’s daughter, his own former step-daughter OR the film’s frank portrayal of a Satanic Mass, with Karloff presiding over an upturned, double-sided cross as its Priest OR the film’s famous climactic scene where Lugosi literally skins Karloff alive OR…

Well, I could go on, and I’ve nowhere near addressed the question posed above, but suffice it to say, folks, this is a wild one and horror fans should definitely take the chance, a mere 65 minutes of viewing time, to marvel at it!

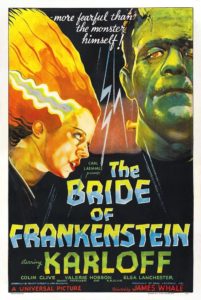

13th Night: THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN

(1935, Universal, dir. James Whale)

One of those cinematic anomalies where the sequel is better than the original, director Whale—in his 4th (and final) offering to the genre—ramps up the style, horror, AND humor for one of the most purely enjoyable horror movies ever made. Opening with a witty prologue set in the famous “haunted summer” of 1816 by Lake Geneva, with Mary Shelley (Elsa Lanchester), husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron (“England’s greatest sinner!) meta-discussing the frankly ludicrous notion of a sequel toFrankenstein, the action returns us to the charred ruins of the original’s famous burning (and now entirely burnt) windmill where the mob of angry villagers heedlessly reawaken The Terror (the one name-billed “Karloff) beneath—and so it begins!

One of those cinematic anomalies where the sequel is better than the original, director Whale—in his 4th (and final) offering to the genre—ramps up the style, horror, AND humor for one of the most purely enjoyable horror movies ever made. Opening with a witty prologue set in the famous “haunted summer” of 1816 by Lake Geneva, with Mary Shelley (Elsa Lanchester), husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron (“England’s greatest sinner!) meta-discussing the frankly ludicrous notion of a sequel toFrankenstein, the action returns us to the charred ruins of the original’s famous burning (and now entirely burnt) windmill where the mob of angry villagers heedlessly reawaken The Terror (the one name-billed “Karloff) beneath—and so it begins!

This time, though, The Monster just wants a ‘friend,’ and the sheer spectacle of the famous ‘Bride’ creation scene—with the buzzing and cracklings of the electrical gizmos, the tilted camera angles, the sinister lighting effects; and all edited rhythmically to Franz Waxman’s powerful score—should not be missed by ANY fan of the genre. And, geez, have I not yet mentioned wild-eyed and bushy-haired Ernest Thesiger as maddest of all scientists, “Dr. Septimus Pretorious”? (How remiss of me.) With his distaff mannerisms and gallows humor—even going so far as in one scene to take his lunch over a young woman’s grave—the Good Doctor doesn’t so much ‘steal’ as ‘stroll mincingly away’ with nearly every scene he’s in: “To a new world of Gods and Monsters!”

As with the original, though, the real laurels go to a performer billed as “?” (Elsa Lanchester; doubling as author Shelley AND her creation’s Bride) who, with white lightning bolt-like streaks zig-zagging up her fright-curled, foot-length hairdo, disdainfully ‘hisses’ her romantic disapproval of the very creature she has been created for, lending itself to one of the most improbably heartbreaking moment in the history of horror movies, much less the history of movies in general!

Haunting Miscellany!

For me, one fascinating aspect of Bride is its re-characterization of Frankenstein’s Monster. Where, in the original, Karloff’s “Monster” had been somewhat sympathetic as a maligned outsider, in the sequel, the Monster is practically saint-like in his persecution, sufferings and torment. Karloff’s soulful performance is the true heart of the film, and, indeed, his entire ‘mission’ throughout the film—which, along the way, involves saving a young shepherdess from drowning, taking (brief) refuge with a gypsy family; culminating in the famous sequence where he shares supper with a blind hermit—is one of simply seeking acceptance in a harsh and cruel world that refuses to accept him.

The Christian imagery director Whale scatters throughout—crucifixes looming large on walls, religious statues and crossed shadows dominating the film’s mise en scene; even going so far, in one scene, as to show the Monster with his arms outstretched while tied to a rail and jeered at by angry villagers—is obviously no accident. And, as if to underline the point, the film ends for the Monster on a note of supreme self-sacrifice… and he’ll even rise again for a sequel (1939’s Son of Frankenstein)!

Who knew? A horror movie tailor-made for Sunday School!

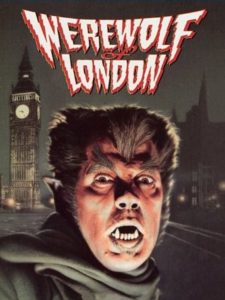

14th Night: WEREWOLF OF LONDON

(1935, Universal, dir. Stuart Walker)

Universal’s first stab (bite? gash? slashing wound?) at a werewolf tale is mostly remembered today for being… well, Universal’s first werewolf movie.

Universal’s first stab (bite? gash? slashing wound?) at a werewolf tale is mostly remembered today for being… well, Universal’s first werewolf movie.

With overtones of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, The Beast crouching just behind the placid exterior of a proper English gentleman (Henry Hull) is unleashed after a botany expedition to the remote mountainous wastes of uncharted Tibet, undertaken to acquire a rare plant specimen called “mariphasa,” gets our intrepid hero attacked (and, of course, bitten) by a werewolf guarding the object of his search. Upon his return, the first full moon rises over the dark city and our celebrated botanist is quickly transformed into a raging, bloodthirsty monster stalking the mist-shrouded streets of Victorian London!

As alluded to above, Hollywood’s first attempt at tackling the werewolf mythos is frequently overshadowed by later, more celebrated, tales of full moon madness. And that’s really a shame ‘cos this early take on lycanthropic mayhem has many imaginative touches—including an atmospheric “London in the Fog” setting—that later versions lack. Also of interest is actor Henry Hull’s striking appearance as the werewolf, who is decidedly taller and leaner than future screen werewolves. Studio makeup artist Jack Pierce’s werewolf design is a scaled-back version of what would appear 7 years later in The Wolfman (up next!).

Haunting Miscellany!

By the latter half of 1935, the public’s enthusiasm for the sort of horror fare Universal had been churning out so relentlessly—and, I should add, brilliantly—over the past four years had waned in favor of bright and witty social comedies such as Columbia’s It Happened One Night (1934).

The studio would still continue to make movies in the “fright” genre in the latter half of the decade, relying increasingly on sequels like Dracula’s Daughter (1936) and Son of Frankenstein (1939), as well as screen team-ups between their biggest horror stars, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, in films like The Raven (1935) and The Invisible Ray (1936), but undoubtedly the largest contributing factor to the studio’s decline during this period was the ousting of young producer, and head of production at Universal from 1928 – 1936, Carl Laemmle, Jr. The son of the studio’s founder, “Junior” Laemmle took control of the studio at the tender age of 20 and, in the early year of the Depression, turned around the then-floundering fortunes of Universal through the major critical and financial success of his 1930 production of All Quiet on the Western Front.

Recalling the success the studio had with two films starring Lon Chaney, on loan from MGM, during the 20’s (1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera), Junior Laemmle re-shifted the focus of the studio during this period towards money-making Tales of the Macabre and, with major emerging stars like Karloff and Lugosi, allowed directors like James Whale and Karl Freund, ably abetted by a whole team of visual effects artists, the space and creative freedom to fashion enduring and iconic horror properties.

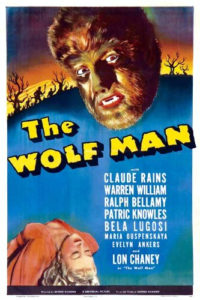

15th Night: THE WOLF MAN

(1941, Universal, dir. George Waggner)

Six years after the studio’s ousting of boy-genius producer “Junior” Laemmle (who, again, had been chiefly responsible for all those great horror movies of the early 30’s), writer Curt Siodmak resurrected (and the choice of words is entirely appropriate) the Universal monster series with his definitive take on the werewolf mythos.

Six years after the studio’s ousting of boy-genius producer “Junior” Laemmle (who, again, had been chiefly responsible for all those great horror movies of the early 30’s), writer Curt Siodmak resurrected (and the choice of words is entirely appropriate) the Universal monster series with his definitive take on the werewolf mythos.

“Larry Talbot” (Lon Chaney, Jr.), an Americanized Welsh/British aristocrat, returns the prodigal son after several years abroad to make amends with his father, “Sir John Talbot” (Claude Rains), and to take his rightful place as heir to the Talbot Estate. The transition proves not without its difficulties, though, after young Talbot, defending a young woman from the village (Evelyn Ankers), is attacked by an unusually hairy traveling gypsy (Bela Lugosi) on the evening of a full moon! (Well, you can probably guess what happens next “when the wolfbane blooms/and the autumn moon is bright.”)

Chaney the Younger proved no-less dedicated to the craft of “extreme characterization” than his protean progenitor and reportedly endured 10 hours daily in make-up master’s Jack Pierce chair, and sitting motionlessly under hot, heavy makeup in front of cinematographer Joseph Valentine camera, to achieve the 10-second on-screen transformation from Man to Wolf Man. If there’s a ‘collective unconscious’ for the movie-going public, I’d say the image of Lon Chaney, Jr.’s snarling, hirsute creature stalking its prey on the misty moors has certainly entered it…

Not to be missed.

Haunting Miscellany!

Along with establishing the werewolf symbol as a ‘starred pentagram,’ Curt Siodmak’s script was also the very first to suggest that a werewolf could only be killed by ‘silver.’ Legend has it Siodmak took his inspiration, oddly enough, from The Lone Ranger radio program which he worked on while writing The Wolfman script. (So, then, if you happen to remember the name of the Lone Ranger’s horse: “Hi-ho, ??????! Away!”)

In addition, Siodmak, the brother of filmmaker Robert Siodmak (1946’s The Killers and 1948’s Criss Cross) also came up with the enduring bit of doggerel quoted above about “[blooming] wolfbane” and “[bright] autumn moon[s],” written to sound like (and often mistaken for) ancient myth that has probably appeared, in one form or other, in every werewolf movie made since.

Indeed, some of my own personal favorites, Joe Dante’s The Howling and John Landis’ An American Werewolf of London (both 1981), would have undoubtedly been impossible to realize without the conventions established by Siodmak’s imagination and vision. As such, it is absolutely astonishing to think that literally everything we today associate with an entire monster mythology was in fact established by a hard-bitten Hollywood scribe on a deadline!

(Just goes to show how great classic Hollywood was, folks.)

16th Night: PHANTOM OF THE OPERA

(1943, Universal, dir. Arthur Lubin)

There’s a bit more Opera than Phantom in Universal’s semi-musical remake of the silent Lon Chaney classic, but this grand Technicolor production is well-worth seeing on its own (considerable) merits. From the film’s first shot—a tight close-up on an opera singer that sweeps back over the audience to pause BEHIND the opera house’s ornate chandelier (a bit of foreshadowing, methinks?)—viewers will know they’re in for a real treat.

There’s a bit more Opera than Phantom in Universal’s semi-musical remake of the silent Lon Chaney classic, but this grand Technicolor production is well-worth seeing on its own (considerable) merits. From the film’s first shot—a tight close-up on an opera singer that sweeps back over the audience to pause BEHIND the opera house’s ornate chandelier (a bit of foreshadowing, methinks?)—viewers will know they’re in for a real treat.

Over-complicated melodramatics naturally ensue, with the love triangle between this version’s Christine (Susanna Foster), the opera’s romantic (and nauseating) light baritone (Nelson Eddy), and the unwanted, possessive attentions of the Phantom himself (Claude Rains), providing the dramatic focus of music-inspired Machiavellian mayhem that literally brings the Grand Opera crumbling to its foundations! Ultimately, this version has more in common with lavish theatrical dramas like Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948) and Jean Renoir’s The Golden Coach (1952) than with a rigidly-defined ‘horror movie,’ and Claude Rains’ subdued, neurotic (and pathologically retiring) “Phantom” offers an interesting contrast to previous (and later) incarnations.

Haunting Miscellany!

A personal favorite of director Martin Scorsese, along with prefiguring the treatment of obsessive, destructive love against a lush, historical background in Luchino Visconti’s anti-romantic classic Senso (1954), Universal’s 1943 Phantom, more a musical than a tale of the macabre, is certainly an anomaly among horror movies. (Though Gaston Leroux’s 1909-10 serial seems to suggest it by its very title, one can very well imagine this particular version of ...Opera inspired the 1986 Andrew Lloyd Webber stage musical, still one of the longest-running theatrical productions of its kind.)

Doing much to humanize the actions and motivations of The Phantom—Lon Chaney’s simply being an unrepentant, unstoppable monster—casting a complex, distinguished actor like Claude Rains, for whom jealousy and lovesick humiliation was something of a specialty, ‘ups’ the class and high culture-quotient to the nth degree and bridges Universal’s ambitions for utilizing semi-legitimate opera singers like Susanna Foster and, more prominently, Nelson Eddy with their already-proven track record with horror movies.

Though plans for a sequel—in which, apparently, The Phantom would have survived having the walls of his subterranean lair collapse upon him in order to wreak further vengeance—were scrapped in favor of the mid-40’s umpteenth House of… monster mash-up, it’s interesting to speculate what further ambitions the studio might have realized had they instead ‘gone in’ for high culture once more as opposed to having each of their horror properties (Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Invisible Man…) “meet” Abbott & Costello. (As entertaining as those pictures are!)

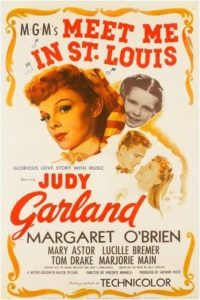

17th Night: MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS

(1944, MGM, dir. Vincente Minnelli)

A Judy Garland musical? On a list of Halloween movies?? Yup.

A Judy Garland musical? On a list of Halloween movies?? Yup.

Chronicling a year in the life of a family from St. Louis—culminating in the 1904 World’s Fair—this eternally delightful film is divided into four equally delightful sections, each detailing one eventful day for the “Smith” family in all the four seasons. This is the sort of nostalgic Americana that audiences were clamoring for in late November of 1944—at this point, almost 3 dark years into the most destructive war in human history—and a bit of musical escapism, courtesy of MGM’s knack for idealized portraits of American families and small town life, seemed made to order.

Director Minnelli, then a mere two films into his long tenure as stylist ne plus ultra at the studio, served up his first true masterpiece with St. Louis, filling each frame with the mise en scene of a bygone age—big houses and spacious lawns (which can apparently be supported on a middle class lawyer’s income), the lush furnishings and bric-a-brac of an overstuffed, post-Victorian interior (complete with a parlor chandelier and upright piano)—that will make any viewer want to get in a time machine and travel back to a time when St. Louis could have been called, with a straight face, “a small town.”

After an opening section that takes place at the end of summer, establishing the characters and family dynamics (set to such memorable selections as the title and “Trolley Song”), the second section, “Autumn – 1903,” takes place, appropriately, on Halloween night. Following the youngest Smith child, “Tootie” (Margaret O’Brien), on her first Halloween, we’re privy to an amusing look at the holiday’s American Folk traditions back when its celebration was much more TRICK than TREAT. Bonfires, homemade costumes (as “a horrible ghost” who “died of a broken heart” and a “terrible drunken ghost… murdered in a den of thieves,” respectively), flinging a handful of flour in one’s kindly neighbor’s face and whispering, very tremulously, “I hate you, Mr. Braukoff!”: the lush, atmospheric Technicolor makes each frame of this ‘haunted evening’ pop off the screen like a beautiful oil painting. Great fun.

Haunting Miscellany!

Judy Garland, as second Smith daughter “Esther,” undoubtedly stands in for the All-American Girl here and, indeed, is given some of the most gorgeous Technicolor close-ups—especially during the famed “Trolley Car” sequence (in which I defy anyone to find her blinking even once)—that any actor had received heretofore under the glaring, million-watt lights of the notoriously demanding photographic process. (And that includes Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind.)

Not surprisingly, the camera was in love with Miss Garland, and that extends to one of the men behind the camera, director Vincente Minelli, who in fact married her the very next year. One minor quibble, though: her frankly incomprehensible hair, which looks as though a family of birds are nesting on top of it. While not quite as distracting a presence as kid star Margaret “Tootie” O’Brien, whose breathless and shrieking style of child performance has not aged well in the intervening 70 years, the offending pile o’ cascading auburn locks that MGM’s wig-makers placed over Garland’s black curls—perhaps in a misguided attempt to compete with co-star Lucille Bremer’s, as eldest sister “Rose,” luscious red hair—is possibly as frightful as any wig donned by Karloff or Lugosi!

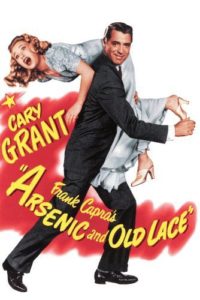

18th Night: ARSENIC AND OLD LACE

(1944, Warner Bros., dir. Frank Capra)

Frank Capra, screenwriters Joseph & Philip Epstein, and a perfect cast of performers adapt Joseph Kesserling’s Broadway smash (whose success delayed the release of this film by THREE years) into the ultimate zany black comedy. Set on Halloween night, this breathless farce concerns the murderous goings-on of the crazy Brewster clan and the frantic efforts of the one not-insane Brewster, “Mortimer” (Cary Grant), to get all his relatives (safely) committed.

Frank Capra, screenwriters Joseph & Philip Epstein, and a perfect cast of performers adapt Joseph Kesserling’s Broadway smash (whose success delayed the release of this film by THREE years) into the ultimate zany black comedy. Set on Halloween night, this breathless farce concerns the murderous goings-on of the crazy Brewster clan and the frantic efforts of the one not-insane Brewster, “Mortimer” (Cary Grant), to get all his relatives (safely) committed.

But even HIS sanity is put to the test as the evening progresses… There’s his brother “Teddy” (John Alexander), who operates under the delusion that he’s the 26th President, charging up the stairs which he thinks is San Juan Hill and burying bodies which he thinks are victims of Yellow Fever in the basement, which he thinks is the Panama Canal; there’s his elderly aunts, “Abby and Martha” (Josephine Hull and Jean Adair), who, in their doily-laced collars and long, bustling skirts, treat lonely travelers to their own ‘family blend’ of elderberry wine (mixed with arsenic, of course); and, most of all, there’s the ill-fated return of the long prodigal eldest Brewster brother, “Jonathan” (Raymond Massey), who has has acquired, through botched plastic surgery (courtesy of Peter Lorre’s “Dr. Einstein”!), a rather unfortunate resemblance to a certain horror movie star (“?”)

If there’s one thing classic Hollywood movies did well, it’s comedy, and this lightning-paced production strikes just the right balance between the over-the-top proceedings and their delightfully sinister undertones. Perfect Halloween viewing.

Haunting Miscellany!

In the original play, the part of the plastic surgery-disfigured, psychopathic gangster Jonathan Brewster was actually PLAYED by Boris Karloff, and this served to make the joke that much funnier whenever any of the characters pointed out the resemblance. Karloff was unavailable for the movie—he was touring with the stage production at the time—but actor Raymond Massey acquitted himself brilliantly under Perc Westmore’s make-up (the “Frankenstein”-like facelift scars are a particularly nice touch) and with a spot-on “Karloff” impersonation.

It’s one among several notes of off-the-wall (even off-the-hook!) humor that shows director Frank Capra at his zaniest, descending the soap box of “social relevance” he at times ascended during otherwise charming pre-war dramadies like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and Meet John Doe (1941), and is certainly the purest comedy in his oeuvre since his days making silent slapstick features with comedian Harry Langdon (The Strong Man, Long Pants). Again, it seems that Capra, at the time also engaged in making Why We Fight documentaries for the U.S. Army, also bowed to the public’s demand for something less heavy and more fun. Posterity, I’d say, couldn’t be more delighted!

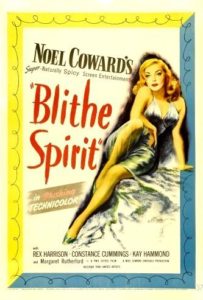

19th Night: BLITHE SPIRIT

(1945, UK, dir. David Lean)

More macabre fun, this time courtesy of playwright Noël Coward and (future) director of epics, David Lean.

More macabre fun, this time courtesy of playwright Noël Coward and (future) director of epics, David Lean.

Mystery writer “Charles Condomine” (Rex Harrison), researching his latest thriller, organizes a séance at his cottage in the English countryside—during which the spirit of his first wife (Kay Hammond) is summoned (accidentally) from the Great Beyond. The subsequent ‘haunting’ wreaks immediate havoc on his SECOND marriage (Constance Cummings)… And that’s just the beginning as further marital and spiritual complications ensue!

During this period in his career, Lean was most well known for adapting the works of Coward for the screen—he had served as a technical advisor (and credited co-director) on Coward’s naval wartime drama, In Which We Serve (1942), as well as previously adapting Coward’s between-the-war British family drama, This Happy Breed (1944)—but this is the first film Lean made for Coward, who served as producer, where visual effects clearly trump the witty and brittle dialogue for which Coward was known.

Shot in muted Technicolor (rather appropriate for its rainy English setting), Lean and his technicians came up with several inventive (and visually compelling) means to suggest the ghostly presence of the spirit(s)—including a light-green makeup design and glow-in-the-dark costumes for the ghostly presence of Condomine’s late first wife, “Elvira” (Kay Hammond), and subtle lighting effects courtesy of cinematographer Ronald Neame. Margaret Rutherford is hilarious in her star-making performance as the eccentric and energetic medium, “Madame Arcati.” Also of note is a surprising twist that changes the ending of the original play.

Haunting Miscellany!

Squarely in the tradition of ghostly comedies and romantic fantasies like The Ghost Goes West (1936),Topper (1937), I Married a Witch (1941), and The Canterville Ghost (1944)—the tradition would continue the following year with Rex Harrison himself playing a ghostly suitor in 20th Century Fox’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1946)—Blithe Spirit offers a pleasant, if slightly naughtier (I mean, the comic situation of a man living with both his living and dead wives suggests not only bigamy, but necrophilia!), variation on spiritualistic goings-on and screwball romance from beyond the grave.

As a point of confession here, after seeing it performed by the American Players Theatre in Spring Green, Wisconsin in the summer of 2011, I very foolishly attempted a 50,000 word, fanfictive “Fourth Act” to Coward’s three-act play, and by extension this film, in which it is revealed that the medium, Madame Arcati, had been the sole author of these otherworldly romantic entanglements in order to drive the husband mad and, for her own dark, inscrutable purposes, take possession of the house! Though I’d cringe to look at it today (I’m reasonably certain all copies have been chucked out, burned, or deleted) I feel I can nonetheless personally attest to the natural, and of course not-so natural, storytelling appeal of This World clashing against The Next — especially for comedy! (Or, in my case, the entirely unintentional kind.)

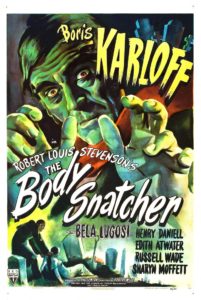

20th Night: THE BODY SNATCHER

(1945, RKO, dir. Robert Wise)

From 1942 to 1946, RKO producer Val Lewton made a series of low-budget ‘program fillers’ (*movies with a short-running time designed to fit the bottom of a double feature), many of which are now regarded as some of the finest Hollywood genre pictures ever made. Director Robert Wise’s The Body Snatcher, based on a Robert Louis Stevenson story, is one of Lewton’s finest, with Boris Karloff sinister and frightening (what else?) as a ‘cabman’ in 1830’s Edinburgh who—shades of the infamous early 19th century graverobbers, Burke & Hare—digs up corpses from graveyards and sells them to a medical college.

From 1942 to 1946, RKO producer Val Lewton made a series of low-budget ‘program fillers’ (*movies with a short-running time designed to fit the bottom of a double feature), many of which are now regarded as some of the finest Hollywood genre pictures ever made. Director Robert Wise’s The Body Snatcher, based on a Robert Louis Stevenson story, is one of Lewton’s finest, with Boris Karloff sinister and frightening (what else?) as a ‘cabman’ in 1830’s Edinburgh who—shades of the infamous early 19th century graverobbers, Burke & Hare—digs up corpses from graveyards and sells them to a medical college.

Naturally, “Cabman Gray” soon resorts to murder when the local gendarmes start guarding the cemeteries and the dedicated, though somewhat austere and morally questionable, “Dr. MacFarlane” (Henry Daniell), heir to the real-life Burke & Hare associate, Dr. Knox, continues to demand a steady supply of medical cadavers. For horror fans, though, the film is most notable as the very last to feature the final on-screen team-up of Karloff and Bela Lugosi. The pair, who had at this point vied for screen dominance in four horror movies together (I’m not really counting 1940’s Black Friday as in that film they didn’t have any mutual scenes), attained a level of intensity in their perhaps all-too-convincing enmity that translates to pure screen electricity.

Bottom-billed Lugosi, who due to drug addiction, multiple marriages, and personal debt had come down considerably in the movie-making world, is here given one crackerjack of a terrific screen send-off when he, playing the mentally feeble medical college dogsbody, “Joseph,” (very foolishly) attempts to blackmail the evil cabbie… The gaping maw of Poverty Row and the delirious ambitions of one Edward D. Wood, Jr. opened up and swallowed Mr. Lugosi whole in his remaining years on the fringes of Hollywood, but here he’s given a final moment of truly blood-curdling glory!

Haunting Miscellany!

While Val Lewton’s psychologically terrifying films dealt only tangentially with supernatural themes, horror aficionados have championed the series for decades due to the films’ ability to conjure up a dark and eerie atmosphere… without once showing a disfigured monster or a set drenched in blood.

Lewton took control of RKO’s unofficial “B” unit in the wake of the studio’s release of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane(1941), and Lewton’s stylistic choices—bold framing, unusual angles, and atmospheric, low-key lighting—along with his films’ unconventional approaches to narrative—some employ a flashback structure, and many others end on a note best-described as “unresolved”—clearly demonstrate a style of Hollywood filmmaking, no less than Welles’ breakthrough classic, that had reached its maturity. Beginning with a collaboration between director Jacques Tourneur and writer DeWitt Bodeen, in which Lewton, Tourneur, and Bodeen were tasked by the studio to make “some kind of horror movie” from the ridiculous title of Cat People (1942), the eight features that followed—including such classics as I Walked with a Zombie (1943; another studio-forced title), The Leopard Man (1943), and the film under discussion, The Body Snatcher—all ran under 80 minutes, were produced very quickly, and, most importantly, at a minimal cost to the studio.

Part of Lewton’s “suggestive” style of filmmaking was due to economics—many of the films were shot on half-finished or leftover sets from other features (indeed, 1943’s Satan Cult thriller The Seventh Victim was mostly filmed in interiors Orson Welles had used for his second feature, 1942’s The Magnificent Ambersons), while the dim lighting served to conceal the productions’ low-cost—but, ultimately, Lewton and his collaborators posited that anything the viewer might imagine within their chiaroscuro compositions would be far scarier than anything that could be created through make-up or flashy effects.

21st Night: 50s TRIPLE CREATURE FEATURE!

If the movies are any judge, the 50’s were a rather disquieting period, with fears ranging from the irrational (i.e., alien invasion) to the very real (i.e., the looming threat of nuclear armageddon). The horror and science fiction genres mined these fears for their entertainment value, creating some of the most memorable creatures committed to celluloid. Following is a few prime examples of ‘monstrosity!’ from that anxious decade:

Take 1: The Threat From Above!

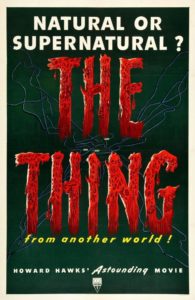

THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD

(1951, RKO, dir.(s) Christian Nyby & Howard Hawks)

Howard Hawks’ study of group dynamics under a pressure situation is just about the most realistic depiction you’ll find of how a ‘first contact’ situation might actually unfold. Remade (sorta) by John Carpenter in 1982 (as The Thing; entirely different, though equally scarifying), the original features a giant, unstoppable vegetable-based life form (described by one character as an “intellectual carrot”) that feeds on animal blood… And it’s really much more frightening than it sounds!

Howard Hawks’ study of group dynamics under a pressure situation is just about the most realistic depiction you’ll find of how a ‘first contact’ situation might actually unfold. Remade (sorta) by John Carpenter in 1982 (as The Thing; entirely different, though equally scarifying), the original features a giant, unstoppable vegetable-based life form (described by one character as an “intellectual carrot”) that feeds on animal blood… And it’s really much more frightening than it sounds!

Take 2: The Inescapable Threat!

THEM!

(1954, Warner Bros., dir. Gordon Douglas)

The atomic age sparked fears of genetic mutation from radiation exposure… which, in turn, inspired a whole rash of “giant nuclear monster” movies. If this (often-dubious) sub-genre has its Citizen Kane, though, it’s undoubtedly Them! Imagining a giant ANT invasion as a potentially apocalyptic event, the movie is infused with a documentary-like reality that makes a viewer feel the full threat of the (admittedly ridiculous-sounding) situation.

The atomic age sparked fears of genetic mutation from radiation exposure… which, in turn, inspired a whole rash of “giant nuclear monster” movies. If this (often-dubious) sub-genre has its Citizen Kane, though, it’s undoubtedly Them! Imagining a giant ANT invasion as a potentially apocalyptic event, the movie is infused with a documentary-like reality that makes a viewer feel the full threat of the (admittedly ridiculous-sounding) situation.

Take 3: The Threat From Within!

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS

(1956, Allied Artists, dir. Don Siegel)

Possibly the most remade, adapted, refashioned, AND parodied science fiction/horror movie of all time, the original has been alternately interpreted as a cautionary tale about conformity, a commentary on social apathy, or an allegory about the unchecked spread of Communism. With its depiction of an entire population corrupted and replaced by exact replicas of THEMSELVES, though, one can’t help being reminded of an observation made by cartoonist Walt Kelly (Pogo) at the height of the political witch hunts of the 1950’s: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” Surely the most frightening monster of them all!

Possibly the most remade, adapted, refashioned, AND parodied science fiction/horror movie of all time, the original has been alternately interpreted as a cautionary tale about conformity, a commentary on social apathy, or an allegory about the unchecked spread of Communism. With its depiction of an entire population corrupted and replaced by exact replicas of THEMSELVES, though, one can’t help being reminded of an observation made by cartoonist Walt Kelly (Pogo) at the height of the political witch hunts of the 1950’s: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” Surely the most frightening monster of them all!

Haunting Miscellany!

Only one of these great genre pictures contains an actual exclamation point in its title (Them!; so-named for the screaming, single-word description given by a little girl, whose family was slaughtered and eaten by giant ants before her very eyes, upon jolting awake from a catatonic stupor), but I think all certainly deserve one.

Growing up in the 80’s, network television (the “big three” of NBC, ABC, and CBS; FOX came along soon after) was still the dominant cultural force in this country and, at the time, was still re-running most of the programs my parents (both born in 1949) had themselves grown up on in the 50’s and 60’s. The Donna Reed Show, Father Knows Best, and (especially) Leave it to Beaver; all presented a white, middle-class, suburban, squeaky-clean image of normality and middle-American contentment—but beneath that placid exterior, one surmises, lurked discontentment, fear, and mass hysteria!

Or at least that’s what the evidence of these horror/scifi pics seems to suggest. With their stalwart, square-jawed heroes (James Arness in Them!, Kevin McCarthy in Body Snatchers) and sometimes brainy, though more often drippy and tight-bloused, heroines (Joan Weldon, Dana Wynter)—in grudging cooperation with those egg-headed scientists (Edmund Gwenn in Them!; Robert Cornthwaite, though not so helpfully, in The Thing)—the disruption to All-American values were entertainingly put through their genre paces by the ever-lurking threat from above (The Thing), below (Them!), or within (Body Snatchers), and undoubtedly lead to their success with film audiences.

22nd Night: PEEPING TOM

(1960, UK, dir. Michael Powell)

Premiering the same year as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Peeping Tom also concerns a serial killer of women (Carl Boehm) given to voyeurism. But where Hitchcock’s movie was greeted with instant acclaim (on the American side of the pond, at least), Michael Powell’s unsettling account of a young assistant cameraman and his bizarre, murderous fetish for the eye of a camera was vilified in the British press, shunned by the public, and ended up virtually destroying the renowned filmmaker’s career.

Premiering the same year as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Peeping Tom also concerns a serial killer of women (Carl Boehm) given to voyeurism. But where Hitchcock’s movie was greeted with instant acclaim (on the American side of the pond, at least), Michael Powell’s unsettling account of a young assistant cameraman and his bizarre, murderous fetish for the eye of a camera was vilified in the British press, shunned by the public, and ended up virtually destroying the renowned filmmaker’s career.

Powell, who with writer/producer Emeric Pressburger, billed mutually as “The Archers,” had been responsible for some of the most ravishing, astonishing, and exciting movies made during and after World War II. Though too numerous to mention, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Red Shoes (1948) remain to this day the high-water mark for the British film industry.

Appearing himself in documentary inserts as the young killer’s late father, a famed behavioral psychiatrist who used his growing son as a guinea pig while researching the causes and effects of fear, Powell, as director/producer, seems intent as a filmmaker in showing, rather than merely suggesting, the seedy underbelly of British urban culture. (The film opens with a direct cut on a long, single take of the murderer meeting a prostitute in a slum, following her upstairs to her squalid bed-sit, and fatally slashing her with a pointed metal object protruding from the camera!)

While many speculate that the fury stemmed from Powell’s stylistic decision to film the murders from the murderer’s perspective (AS he’s ‘shooting’ his murders!), personally I think the entire hullaballo boiled down to a five-second shot of a murder victim sprawled nude on a bed. THAT’s what really ruffled everyone’s feathers! In any event, “Banned in England!” has such a nice ring to it and, as cinephiles the world over can tell you, any film that’s earned the distinction is well-worth a look-see…

Haunting Miscellany!

As long as we’re mentioning ‘firsts,’ where Peeping Tom might have been the first British film to contain a shot of a nude woman, Psycho has its own unusual distinction as the first American film to show a toilet in a bathroom. (Seriously!) One surmises that American film audiences, after over 25 years of Hollywood self-censorship, were perhaps now ready for such a shocking image (finally!), but director Powell, in his first sole filmmaking venture since his days churning out “Quota Quickies” during the 1930’s, seriously overestimated his own audience’s changing tastes.

Peeping Tom came at a time when British society, historically glacial to accept any sort of change whatsoever, actually was changing—the Empire had crumbled, the class system was breaking down to the point of virtual disintegration—but still, there were certain topics, themes, and images for the British moviegoing public (fetishistic sexuality, murderous voyeurism, and, well, a woman’s bare breasts, respectively) that were not quite cricket!

23rd Night: THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL

(1962, Mexico, dir. Luis Buñuel)

A group of wealthy elite gathers for an elaborate dinner party… and find they can’t leave the room when the evening ends. Days, weeks pass and the guests—inexplicably ‘trapped’—resort to an escalating series of humiliations in order to survive. One by one, the illusions of cultured society recede, dissipate, and disappear as these members of the upper crust are reduced to the basest forms of savagery…

A group of wealthy elite gathers for an elaborate dinner party… and find they can’t leave the room when the evening ends. Days, weeks pass and the guests—inexplicably ‘trapped’—resort to an escalating series of humiliations in order to survive. One by one, the illusions of cultured society recede, dissipate, and disappear as these members of the upper crust are reduced to the basest forms of savagery…

Obviously, the passing of 30 years certainly hadn’t mellowed the enfant terrible who made L’Age d’Or and here Buñuel came up with one of his more outrageous concepts. Part of the power of a Buñuel film is how a completely ludicrous situation is played absolutely straight—I mean, his actors might as well be performing in a stiff TV drama—and, moreover, how faultless the internal logic of each increasingly bizarre plot development is. As such, the conclusion to all the preceding insanity is PERFECT… and, of course, completely logical. Again, a surrealist art film seems an unlikely candidate for a Halloween-themed movie, but as with many great horror movies Buñuel here smuggles in some still-timely and subversive themes that continue to gain relevance.

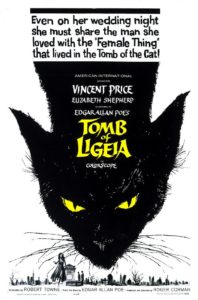

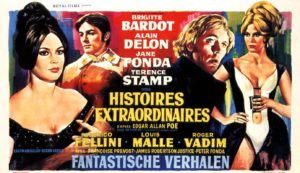

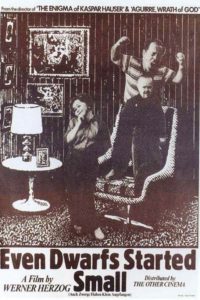

Haunting Miscellany!