Woody Allen Still Believes… But In What?

DIRECTED BY WOODY ALLEN/2014

Woody Allen may not believe in God, but he does believe in magic. This much has been clear for years, at least since “Oedipus Wrecks”, his entry in the 1991 anthology film New York Stories, in which a hapless magician’s mother vanishes only to reappear in the sky over all of Manhattan as unescapable omnipresent nag, calling out his every flaw to all the world. Allen plays the flummoxed magician, and Mae Questel is the newly disembodied mother. It’s a silly bit of psycho-analytical fluff, but perfectly passable.

Woody Allen may not believe in God, but he does believe in magic. This much has been clear for years, at least since “Oedipus Wrecks”, his entry in the 1991 anthology film New York Stories, in which a hapless magician’s mother vanishes only to reappear in the sky over all of Manhattan as unescapable omnipresent nag, calling out his every flaw to all the world. Allen plays the flummoxed magician, and Mae Questel is the newly disembodied mother. It’s a silly bit of psycho-analytical fluff, but perfectly passable.

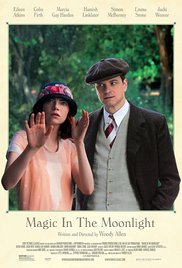

So too is Magic in the Moonlight, Allen’s latest product courtesy of the systematic annual filmmaking treadmill he’s been exercising upon for most of his career. Thankfully, Magic doesn’t feel systematic, which is thanks in part to its early 20th century upper-class period setting, but more-so to its cast, led by a well-matched Colin Firth and Emma Stone.

Both Allen newbies, they’re nonetheless perfect for their roles, he playing a self-assured Brit and sour veteran stage magician named Stanley (his cringe-inducing theatrical alter ego is that of Wei Ling Soo, playing up the “oriental exoticism” fascination of the day to the hilt; and in the process demonstrating that how no matter how enlightened we view ourselves, time will reveal our blind-spots), and her playing Sophie, a charming American tart who happens to be latest psychic medium to hit Europe. (Her glassy eyed trance bit is a charming bit of ham and cheese, carried off wonderfully by the actress.)

Stanley moonlights as the foremost debunker of such malarkey, constantly making it known that there is, in his studied and rigid opinion, no such thing as the paranormal, the telepathic, the spiritual. Sophie, on the other hand, being Emma Stone, is all soul, charm, and magnetism. He is brought in to expose her, a seemingly routine assignment that turns perplexing; so much so it has Stanley second guessing his tightly-held views. Thus, we have the cat and mouse game of him trying to denounce her while simultaneously resisting falling in love with her.

Supporting players Jacki Weaver, Hamish Linklater, Simon McBurney, and Marcia Gay Harden make the most of the fine scraps they’re given. Cinematographer Darius Khondji re-teams with Allen once again for another effectively crisp and sunny romp (following To Rome with Love, Midnight in Paris, and Anything Else, with another on the way), venturing that much further beyond the Fincher/Haneke weight he’s built his name upon. The period look and wardrobe is impeccable, even if the Bergman-lite comedy tension of “Thank God there is no God!” feels a tad played out at times. The Fellini-lite notions of magic in the movies, and the inner life of the showman, on the other hand, is where the sharpness lies.

To be sure, neither Firth nor Stone were hired to stretch their established talents and personas. But their safe presence assures a more appealing gateway to the film than perhaps the currently controversy-embroiled Allen could otherwise realistically expect, and in that light, offers the film’s most interesting meta-reading. Certainly even the most gossip-cloistered of Woody Allen’s National Public Radio-listening fan-base is familiar with the recent accusations against the filmmaker brought forth by his ex, Mia Farrow.

In his review for Film Comment, critic Nicolas Rapold closed out by stating that he couldn’t help but notice that “the film’s suspense derives primarily from the spectacle of an older entertainer trying to prove that a young woman is lying.” It’s probably safe to assume that Rapold isn’t the only one to take note of this, although if one does in fact opt to go down this rabbit hole of analysis (and I sympathize with Rapold’s hesitation to do so), that’s where the most discussable subtext lies in this otherwise frothy outing. If Firth is the obligatory Allen surrogate, (and he is,) then why is he so non-likeable exasperated while Stone remains her lovable, irresistible self? And why then did he script it into a romantic comedy wherein these two opposing polarities (atheist vs. spiritual, British vs. American, older man vs. younger woman, etc.) are inevitably drawn together? We’re either looking at one heck of a couch trip metaphor, or a handy coincidence. There’s little question which Allen, ever the denier, would select.

Whatever that case may be, Magic in the Moonlight, as a film, will likely remain untainted by all the controversy and intensely negative finger pointing of last year. That’s the case even though his character falling for a much younger girl in his essential film Manhattan continues to be widely read as a precursor to his real life relationship with the woman who remains his wife all these many years following that scandal. Perhaps we’ve simply become accustomed to seeing Allen’s male leads go for perky younger dream girls. Or maybe the National Public Radio crowd has simply been waiting for these two particularly favored bulletproof specimens, Mr. Darcy and Easy A, to finally make sophisticated googly eyes at one another. Whatever it is, there is indeed chemistry in the film, if not exactly magic.

Woody Allen has pulled one more rabbit from his old man hat, even in this twilight of his career. It may not be the unexpected wild hare that we go in hoping for (see Match Point for that), but it is that fine and tidy white hare that we’ve come to expect. And although Allen makes it clear that he does not believe in God, we can nonetheless thank the Man Upstairs that he’s still crafting good work, and that he got Colin Firth and Emma Stone to look and play fancy in a romantic comedy.