James Brown Biopic Gets Down With Its Bad Self

DIRECTED BY TATE TAYLOR/2014

The brand new James Brown biopic Get On Up is a mixed bag, both admirable and aggravating. It manages to wear out it’s welcome with only a few bad scenes. It’s both boring and totally engaging; inert while dancing up a storm. It’s impressive and exhausting; showing too much of the life of godfather of soul, yet we come away knowing very little. Get On Up, for all it’s commendable attention to period and visual detail and performances, is all mixed up. And for the love of mercy, I can’t figure out why.

The brand new James Brown biopic Get On Up is a mixed bag, both admirable and aggravating. It manages to wear out it’s welcome with only a few bad scenes. It’s both boring and totally engaging; inert while dancing up a storm. It’s impressive and exhausting; showing too much of the life of godfather of soul, yet we come away knowing very little. Get On Up, for all it’s commendable attention to period and visual detail and performances, is all mixed up. And for the love of mercy, I can’t figure out why.

Director Tate Taylor of The Help fame still hasn’t learned that a two and a half hour running time does not add gravitas to already challenging subject matter. He does seem to know that biopics tend to either over-glorify their subjects, or drag them through the mud. Unable to pick one, he opts for both, with a few scenes purely devoted to what an amazing entertainer and music innovator Brown was, then a scene of him beating his wife. History tells us that Brown was an uneasy person, so embellishment likely isn’t the problem so much as tonal haphazardness in the storytelling.

It’s both boring and totally engaging; inert while dancing up a storm. It’s impressive and exhausting; showing too much of the life of godfather of soul, yet we come away knowing very little.

Told in a non-linear fashion, the first hour of Get On Up might be the best film of the year. It sets up the audience with a series of generations-jumbled scenes, as compelling as they are curiously mismatched. Taylor goes a highly unconventional route, opening his film in 1988 as a shotgun toting James Brown in a bad warm-up suit comically terrorizes a room full of seminar goers over who took a dump in his building’s restroom. It immediately renders the legendary singer a different type of cartoon than he may’ve already been imagined as, leaving viewers deliciously on the hook to find out how and why Brown gots so cah-razy. Unfortunately, as Get On Up goes on down for another ninety minutes beyond that first set-up hour, only continuing to ask the same questions again and again with no big payback, leading us no closer to the answer of who James Brown the person was, and worse, disengaging us from any initial curiosity.

“Huuuh!”

Also, Taylor is overly keen to avoid the kind of music biopic cliches that generated Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story. So to overcompensate, he freely, fearlessly, and often foolishly goes out on a high-wire, allowing his subject to not only break the fourth wall and address the audience, but to do so while enunciating gibberish. The thing is, the movie runs long enough that eventually the cliches do indeed show up. The scenes with Brown, in the midst of stardom, dealing with the mother who’d done him wrong as a child are okay on their own, but the moment of a grown-up Brown, after attempting to flee the police, is shown symbolically as his boyhood self when caught, is the biggest cringe moment in recent movies. (Far worse than the obligatory time James Brown comically says “Oh, hell no!”)

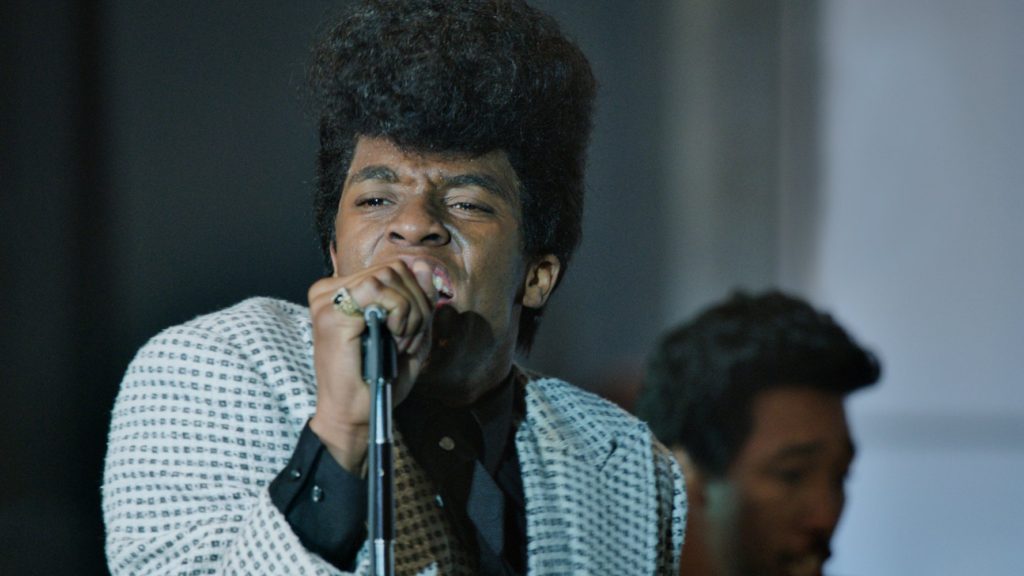

But, it’s worth it for Chadwick Boseman’s masterful channelling of Brown. Cutting arbitrarily from one time and place to another, one moment it’s Boseman (who hit the scene when he played baseball legend Jackie Robinson in the unintentional children’s film, 42) in a high pompadour-fro performing on an early 1960s TV teenage dance show, then in the next scene his hair is trimmed, it’s the late sixties as he’s fearlessly riding a damaged cargo plane into Vietnam to entertain the troops. Then just as abruptly, it’s the seventies, and he’s got his famous straightened Andrew Johnson hair. The looks are all nailed, and the actor runs the aging gamut well. But none of that compensates for the said scenes lack of exclamation or placement within the film as a whole. Some are really good, and others are utterly embarrassing, but on the whole, they play more like randomly shuffled flashcards, or if someone hit “random” while playing a chronological DVD of Get On Up.

“Oww!”

Taylor’s carried over several key African-American actresses from The Help (Viola Davis and Octavia Spencer) to winning effect. The co-starring presence of Dan Akyroyd, however, doesn’t work out. At all. This is Boseman’s party, pure and simple. (Not even a one-time Blues Brother can put a wrinkle in that.) His lip synch might be sketchy during the many rip-roaring performance scenes, but only for falling victim to his mash-potatoed energy funk. By the beginning of the third hour, Taylor is all too happy to turn the film completely over to Boseman for an extended James Brown full-funk concert sequence, circa the early 1970s.

There’s a lot to admire about Get On Up, just as long as one doesn’t come expecting any discernible statements about civil rights (apparently apropos to Brown’s own murky political life), or an understanding of who James Brown truly was, beyond an impenetrable brick wall of a man. Get On Upis, for all it’s very impressive qualities, up to only one thing: Brown getting down with his bad self.

“Huh!”