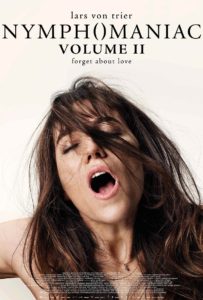

She’s A Nymphomaniac, Nymphomaniac, That’s For Sure

Before reading this review, I would strongly advise you to read Paul Hibbard’s review of Nymph( )maniac: Volume I.

DIRECTOR: LARS VON TRIER/2014

Nymph( )maniac: Volume II is not a complete film, in the same way that other “Part II” films are (Kill Bill springs to mind). I believe this is because Nymph( )maniac was never really intended to be split in half. In fact, in writer/director Lars Von Trier’s native Denmark, the full five-and-a-half-hour uncut version was shown, and it’s clear that this is the best representation of his vision. As such, I certainly do not recommend viewing Volume II in a vacuum, and I suspect that the best way to experience Nymph( )maniac is in its unaltered and original state—perhaps with an intermission or two, but no more than fifteen minutes at a time. Certainly this would be a challenge, but even viewing the “softer” edit[1] that was split into two films would be a bridge too far for most moviegoers. So if you’re going to dive in, I say dive in all the way. Unfortunately, I don’t know if any way American audiences can find the original cut, but my understanding is that Von Trier is planning to release it in some format later on this year. Until then, we can do our best to appreciate this film, but I’m not sure if that’s fully possible without experiencing his complete work.

Nymph( )maniac: Volume II is not a complete film, in the same way that other “Part II” films are (Kill Bill springs to mind). I believe this is because Nymph( )maniac was never really intended to be split in half. In fact, in writer/director Lars Von Trier’s native Denmark, the full five-and-a-half-hour uncut version was shown, and it’s clear that this is the best representation of his vision. As such, I certainly do not recommend viewing Volume II in a vacuum, and I suspect that the best way to experience Nymph( )maniac is in its unaltered and original state—perhaps with an intermission or two, but no more than fifteen minutes at a time. Certainly this would be a challenge, but even viewing the “softer” edit[1] that was split into two films would be a bridge too far for most moviegoers. So if you’re going to dive in, I say dive in all the way. Unfortunately, I don’t know if any way American audiences can find the original cut, but my understanding is that Von Trier is planning to release it in some format later on this year. Until then, we can do our best to appreciate this film, but I’m not sure if that’s fully possible without experiencing his complete work.

This is the third film in Von Trier’s “Depression” trilogy, which includes Antichrist and Melancholia. As Von Trier is an artist who himself struggles with crippling depression, I don’t believe it would be a reach to infer that this trilogy of films might be some of the most personal work in his filmography, in terms of wrestling with his own inner self on film.

Stacey Martin, who plays the central character of Joe as a teenager and young woman, said in an interview that every main character in the film is actually meant to be a reflection of the filmmaker, or some facet of his personality. Meaning that “Nymph( )maniac” is a look into his psyche—a fever dream in the tradition of psychoanalytics in which every figure represents an aspect of the dreamer.

The way in which the story is told in flashback as a conversation between two opposites (man and woman, nymphomaniac and asexual, lustful emotion and intellectual detachment) represent an interplay of oppositional Jungian archetypes hashing it out. This becomes even clearer in Volume II, which begins with a chapter entitled “The Eastern and the Western Church,” inspired by a conversation Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård) have about the Great Schism of 1054, in which the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches separated. This separation is mirrored in the growing schism between Joe and Seligman, as he begins to find himself more consternated by her story. This is evidenced in both the performance of the actors as well as the framing, which sees more and more space on the screen between the two characters, representing the growing emotional distance between them as their relationship begins to deteriorate.

Charlotte Gainsbourg as Joe

In the church metaphor, Seligman the asexual, with his intellectual detachment, represents the Eastern Church (indeed, the metaphor initiates when Joe notices an Orthodox icon hanging on Seligman’s wall). By contrast, Joe the nymphomaniac, obsessed with her body, represents the Western Church. Von Trier further distinguishes the two by characterizing the Western Church with pain and suffering and the Eastern Church with joy. This is why Seligman initially comes off as more welcoming and forgiving of Joe, while she encapsulates self-loathing and a craving for penance (in a section of the film in which Joe seeks sexual gratification through BDSM[2], she even seems to subvert the Passion at one point as her Dom gives her the “Roman maximum” of 40 lashes[3] with a cat-o-nine-tails, while Joe is tied down to a couch in something that resembles a sort of inverted crucifixion pose).

It would be worth noting at this point that I believe the Roman Catholic Church to have one of the most positive and Biblical theologies of the body in all of Christendom—though to be fair, this does not tend to extend to sexuality, but merely an incorporation of good materialism into Christian theology. It is also worth noting, and rather telling, that Von Trier himself once attempted a conversion to Catholicism, although he now considers himself more of an atheist. This, too, is represented in the character of Seligman, who regards the Western Church with distaste but is drawn to the Eastern Church in spite of his agnosticism.

Lars Von Trier

Seligman is a stand-in for Von Trier, but then, so is Joe. Nymph( )maniac is actually the filmmaker having a conversation with himself. Joe and Seligman are his anima and animus; self and shadow; playing off each other. In this way, Nymph( )maniac is a cross-section of Von Trier’s mind—or at least his id. For a man who claims to be afraid of everything except filmmaking, it seems that it is in filmmaking where he finds the courage to pour himself out, raw and exposed, and be truly vulnerable to the world. That takes a lot of guts.

Once exposed, those guts are revealed as a twisted mass of cynical darkness, reflecting with brutal honesty the filmmaker’s journey through the valley of the shadow of death. As such, Nymph( )maniac comes across as very pessimistic, misanthropic, and almost nihilistic. I applaud it for being a frank and open discussion about sexuality (a topic which both Western and Christian culture has all-too-often stuffed into a dark closet to be ignored). I only wish it didn’t end up being so sex-negative in the end. But anything else would be dishonest on Von Trier’s part, and I certainly wouldn’t want dishonesty from one of the most notoriously honest filmmakers of our time, who consistently says what’s on his mind (some would say vomits up), no matter who is offended by it. Von Trier has a very low view of humanity, and of human sexuality as well, it would seem. His regard (or lack thereof) for the human body seems almost gnostic, as if he wants to make sex as disgusting for the viewer as he seems to find it—despite the explicitness of this film, it’s actually quite un-erotic. Reading between the lines, one would certainly be forgiven for inferring that his ideal is a sexless existence—or rather, an existence that transcends sex—and perhaps love as well.

While I may not agree with all of Von Trier’s conclusions, there is nonetheless a lot of valuable truth to be discovered here, on a subject which is discussed with a disheartening rarity. Therefore, I would consider Nymph( )maniac to be essential viewing for those with the stomach for it. Not only is it profoundly thought-provoking, but it is beautifully made, even in all its ugliness.

[1] Even the so-called “softer” version, which went out unrated, features explicit scenes of unsimulated, penetrative sexual intercourse, and would be the hardest NC-17 this critic has ever seen. I can only imagine how much more graphic the uncut version is.

[2] Bondage-Domination-Sado-Masochism, for the uninitiated

[3] Here Seligman corrects her, saying the Roman maximum was actually 39 lashes, as they had to be administered in groups of 3, which 40 is not divisible by.