Reflecting on Existential Horror

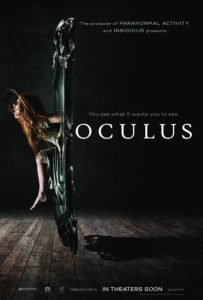

DIRECTOR: MIKE FLANAGAN/2014

Oculus is the rare horror film that focuses on concepts and ideas rather than shocks or thrills. This isn’t to say that it isn’t scary, but rather that the type of terror being traded on here is less the pulse-racing, make-you-jump-out-of-your-seat type, and more of the unsettling, troubling, keep-you-awake-at-night type. It’s a movie that trusts its stories and its themes to sell the horror—questioning the nature of memory, sanity, perception, and possibly even reality itself.

Oculus is the rare horror film that focuses on concepts and ideas rather than shocks or thrills. This isn’t to say that it isn’t scary, but rather that the type of terror being traded on here is less the pulse-racing, make-you-jump-out-of-your-seat type, and more of the unsettling, troubling, keep-you-awake-at-night type. It’s a movie that trusts its stories and its themes to sell the horror—questioning the nature of memory, sanity, perception, and possibly even reality itself.

The film takes place in two time periods simultaneously: both the present-day, and eleven years prior—representing the two most significant events in the lives of siblings Kaylie and Tim Russell (Karen Gillan[1] and Brenton Thwaits). Both of these timelines unfold in the same location—the family’s house: lived-in in the past; deserted and empty in the present. As events unfold across these two separate timeframes, the line between them becomes more and more blurred and fluid, as memories of the past are triggered and unearthed by events in the present—memories that may or may not be real—especially when they conflict with each other. Like two worlds colliding, past and present become integrated, sometimes even beyond distinguishability.

The word “oculus” can mean a few different things, but its basic meaning is a fancy term for the eye. As such, the film Oculus is primarily concerned with perception, both literal and figurative. The movie asks us how much we can trust what we see with our own two eyes, as well as in our metaphorical mind’s eye. How trustworthy is memory—specifically memory that has been impacted by trauma? How does our mind seek to protect and/or fool us by making us see things that aren’t there, or convincing us that we’ve seen something we didn’t really see—or perhaps that we didn’t see something that we really did see? What is the difference between reality and imagination? Does it even matter, or is the question merely academic?

In the movie, the catalyst for these questions is a mirror—another type of oculus—an eye through which we see the world both as it is and as it isn’t. Mirrors are strange phenomena through which we are able to intimately interact with ourselves, almost as if our reflection were a separate person.

For animals and babies, it might as well be. At some point in early development we grow to understand the concept of light bouncing off a reflective surface, but there’s still something eerily and intangibly mysterious about using your own eyes to look into your own eyes.

According to ancient tradition, the reflection was actually the invisible made visible—a means through which we are able to perceive our own soul.[2] But this came with its own set of unsettling fears. What if the mirror sees both ways? What if our reflection is somehow able to perceive us? Does our soul leave our body when we see it in the mirror? What if we ourselves somehow become the reflection? Or more frightening still, what if the mirror is a gateway for something else to see into our heart of hearts?

Haunted Mirror stories are nothing new in weird fiction and folklore. Going all the way back to the ancient myths and legends of many archaic cultures around the world, mirrors have been believed to be everything from windows into alternate realities; to tools of divination; to traps for capturing a man’s life force. In ancient Rome, mirrors were associated with the goddess Venus, and to this day, the superstitious believe breaking a mirror will bring you seven years of bad luck. In faerie stories, witches and sorcerers make use of magic mirrors, often for nefarious purposes. Lewis Carroll used a mirror as a doorway for Alice to traverse into a bizarre fantasy realm, but in more recent folklore, the door has opened the other way, allowing terrifying spectres like Bloody Mary and the Candyman to enter into our world.

Oculus is a bit more subtle than this. While the film does feature ghastly apparitions, we are never quite sure as to whether they are objectively real, or figments of our protagonists’ terrified imaginations. The mirror itself is a passive observer, embodying whatever significance is bestowed upon it—is it an autonomously supernatural and malevolent force of evil, or merely an inanimate object of obsession for a troubled mind?

Oculus challenges and frightens on an existential level, existing in the tension between the natural and the supernatural, engaging two distinct unknowable possibilities—either the reality of evil is prescient, or the mind is fragile and spinning into chaos. Of course, either extreme is terrifying; for what is more terrifying than being completely out of control—whether at the mercy of an unknown force from Beyond, or the sputtering and jibbering of a broken and deteriorating mind? Surely these are two of the most horrific things that we might come into contact with.

Oculus is a fascinating horror film because it doesn’t rely on jump scares but on complicated ideas, and is thus much more likely to stick with you afterwards, even if it won’t give you the momentary shocks and jolts that another scary movie might give you. It’s much more of a slow burn, percolating with an ambiguous sense of uneasiness that seems to be just on the cusp of being uncomfortably real.