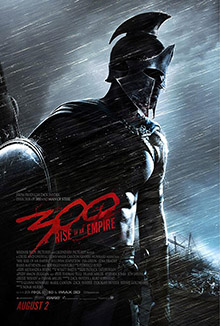

Does The New 300 Stand With The Original?

DIRECTOR: NOAM MURRO/2014

To call 300: Rise of an Empire a sequel to 300 would be reductive; it’s actually a sequel, a prequel, and a companion piece all at once, taking place before, during, and after the events of the previous film. It’s a somewhat novel and admirably non-linear way to make a second installment, ignoring traditional parameters of timing and instead widening the focus. If 300 was a close-up, then Rise of an Empire is writer-producer Zack Snyder (who directed the first movie[1]) taking the camera and suddenly zooming out, showing us the events of the previous film in the larger historical context of the Second Persian Invasion of Greece (482-449 BCE), which these movies are (very) loosely based on.

To call 300: Rise of an Empire a sequel to 300 would be reductive; it’s actually a sequel, a prequel, and a companion piece all at once, taking place before, during, and after the events of the previous film. It’s a somewhat novel and admirably non-linear way to make a second installment, ignoring traditional parameters of timing and instead widening the focus. If 300 was a close-up, then Rise of an Empire is writer-producer Zack Snyder (who directed the first movie[1]) taking the camera and suddenly zooming out, showing us the events of the previous film in the larger historical context of the Second Persian Invasion of Greece (482-449 BCE), which these movies are (very) loosely based on.

It’s an interesting move; one of several the filmmakers could have taken. Even though 300 didn’t really need a sequel per se, the fact that some version of these events actually happened means that there were several more options open to the filmmakers in terms of a second installment. For example, a prequel set at the Battle of Marathon; a sequel that shows the Naval Battle of Salamis; even a side-quel about the Battle of Artemisium, which was happening simultaneously with the Battle of Thermopylae depicted in 300. But rather than pick just one of these options, Rise of an Empire says, “Screw it, I’m gonna be all three of those things at the same time.”

On paper, this sounds like flirting with disaster. Most movies that try to do everything aren’t good at doing anything. Yet Rise of the Empire somehow manages to straddle that fine line between genius and insanity and ride it like a cowboy on a bucking bronco. This novel, non-linear approach ends up working far better than it has any right to. Sure, it’s a throw-your-cake-at-the-wall-and-eat-what-sticks approach, but I’m happy to report not only is this cake super-sticky, but it’s damn tasty too. We get a prologue at Marathon; a climax at Salamis, and the bulk of the movie takes place at Artemisium. But wait—there’s more! Like 300, most of Rise of an Empire is told in flashback, but this time, we get bonus flashbacks within that flashback, like some kind of flashback inception (this movie is structured a lot like an Anne Rice novel at times). Meanwhile, we also check in with the events of the first film from time to time, as they simultaneously unfold alongside the events of this one. We get a look at the socio-political context framing these events, what led up to those events, and how those events effected the rest of the Greco-Persian war. On top of all of that, we also get multiple origin stories: the rise of the god-king Xerxes, which we discover is tied to the origin of our new hero, the Athenian General Themistocles. We also get the back-story for our charismatic new villain: Artemisia (Eva Green), the beautiful but deadly Greek-born commander of the Persian Navy.[2]

Eva Green is a revelation in this film. She’s incredibly sexy and incredibly terrifying (often at the same time); a more than formidable bad-ass to rival anyone else in this series. Green brings just the right amount of calculated yet tragic insanity to the role, playing Artemisia as deeply disturbed, yet totally in control—she’s making the best of a nightmarish past, hardened by adversity into both an expert scrapper and a brilliant manipulator. In short, she’s become what she had to become in order not just to survive, but to flourish. And Eva Green is so charismatically sadistic and memorable in this role, that I now want Zack Snyder to film new scenes with her in order to edit them into the first 300, even though that kind of George Lucas monkey-shining goes against everything I believe in when it comes to the art of film. But Green is just that good as the breakout star of this movie, which I sincerely hope catapults her into household name-recognition status[3]. Her biggest role prior to this was as a Bond girl, but Rise of an Empire proves that she can do so much more.

I have a feeling that when this movie is remembered down the line, it’s going to be thanks to Eva Green.

She steals the show right out from under everyone else in the movie, including her main rival, Themistocles (Australian actor Sullivan Stapleton [Gangster Squad]). That’s not to say he doesn’t do serviceable work here—it’s impressive enough that he manages to hold his own against Green and not get completely eclipsed by her, even if she dominates the screen (and all the men around her) the entire time. It helps that Stapleton is just as pretty as Green is, and that they only share the screen together twice—but boy-howdy, what a couple of scenes.

Their first scene together involves what I can only describe as a “sex fight,” and it perfectly illustrates what I’m talking about. Artemisia, having invited Themistocles onto her barge during a lull in the fighting (a parallel to the scene in the first movie where Xerxes parlays with Leonidas, making everyone uncomfortable in the process) in order to seduce him over to the dark side. It isn’t long before seduction turns into full-on fornication. But in a marked contrast to the tender and caring (if explicit) lovemaking between Leonidas and his wife Gorgo in 300, this scene is all angry screwing between two people who hate each other and everything they stand for, jockeying for position the entire time. It’s darkly and violently erotic, and ends in a stalemate—Themistocles more or less gains the moral high ground (such as it is), but Artemisia wins at sex—something she’s only too happy to remind him of later in one of the best one-liner insults I’ve heard since Blade Trinity.

One of the big themes in Rise of an Empire is manipulation: the behind-the-scenes political maneuvering that sends empires to war with one another, and the puppet masters who prop up oligarchs for their own purposes. Themistocles manipulates the Greek city-states into uniting for the greater good, and manipulates Sparta into sacrificing itself for a dream it doesn’t even believe in. Artemisia manipulates Xerxes from her own position of power, fashioning him into a symbol of false godhood and using him to enable her own vendetta against Greece. When these two tacticians meet in battle, it’s like they’re playing chess with each other across the open sea. This is actually one of the big strengths of Rise of the Empire, as well as yet another aspect that makes it distinctive from 300: the strategies and creative battle maneuvers that keep things very interesting. Anyone who geeks out over war tactics and battle strategies is going to have a field day with the Battle of Artemisium.

Another thing that distinguishes this movie from the original is its perspective on war. 300 was shown from the viewpoint of the hyper-violent Spartans, who were born and bred for warfare. As a result, the first movie almost came off as a series of propaganda reels about the glory of battle. But this time around, we witness those events through the eyes of other characters with radically different perspectives. The heroes of Rise of an Empire are the more civilized Athenians, who see war as a necessary evil and something to be mourned, not celebrated. In fact, much is made in Rise of an Empire about the shortcomings of the Spartan mindset—Themistocles basically sees them as barbarians who are good for basically two things: a blunt object to hammer away at the enemy with, and an inspiring sacrifice to rally the rest of Greece to the cause. So while from a visual standpoint,Rise of an Empire is a natural evolution from 300, part of that evolution means exploring new ground in terms of themes and ideas. Interestingly enough, this makes up for some of the gross historical inaccuracies of the first movie, which ignores the sacking of Athens, which happened after the Battle of Thermopylae, and was essentially ignored in the last film. But here we see it in gory detail—new director Noam Murro doesn’t shy away from showing the consequences of what went down at the Hot Gates.

I can’t help but think that a lot of this has to do with what has happened in the world since the release of the first movie. 300 was released at the height of two foreign wars[4], while George Bush Jr. was still in power and patriotism still meant being hawkish to a lot of people. It was much more heavily influenced by Frank Miller, an anti-Arab curmudgeon who was essentially broken by 9/11. The Spartans looked and sounded a lot like us at the time—making grand speeches about freedom and liberty (never mind the fact that historical Sparta was a feudalistic slave state in which freedom was reserved only for the elite ruling minority[5]), standing against an oppressive army of the demonized “other.” It was about as “us vs. them” as it gets. By contrast, Rise of an Empire is a movie from the Obama era—we have less tolerance for intolerance these days, and we’re almost as tired as war as the Greeks in the movie are (though most of us haven’t witnessed the horrors of it firsthand as they have)[6]; we’re grateful that our global campaigns are winding down and that our soldiers are coming home. Many of us feel very differently about foreign policy than we did ten years ago, and we’re much more global than nationalistic in our perspective. So with the current generation leaning left, and peace looking more attainable than it has in years, a movie extolling the virtues of war would go over about as well as a lead balloon right about now.

In that sense, Rise of the Empire is being intentionally subversive—not just to the first movie, but also to the cultural context it existed in. 300 told us that war is glorious; Rise of an Empire tells us that war is stupid and childish. Does that make it inconsistent, then, when the battle scenes are almost as cool as they were in the first film (contrast with Ridley Scott’s Gladiator [2000], in which the battle sequences were chaotic, grimy, and ugly)? Or does it make Rise of an Empire more subversive—showing kick-ass naval action while secretly laughing at those who think it’s the coolest thing ever? And how effective is it, either way? The feminism of the film begs the question as well—the Snyders’ influence in this regard is essential to what makes Artemisia work as a character, yet I distinctively heard some misogynist meat-heads behind me rooting for her to get her comeuppance. Guys like that are certainly getting their quotient of blood-n-boobs here, but I can’t help but smile to myself when I think about how they’re also getting a healthy dose of feminism along with their testosterone…much like what Joss Whedon was doing with Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

We likely won’t know for sure how much of the subversiveness was intentional and how much I’m reading into it until someone asks the question in an interview, or we hear the audio commentary on the Blu-Ray; it’s the type of give-and-take between the artist and the audience that really makes our own craft as critics worthwhile—navigating the dichotomy between Death of the Author and Authorial Intent; having a conversation with the filmmakers instead of just sitting back and letting the spectacle wash over us. It’s one of the things that frustrated me the most about the response to some of Snyder’s other films—a lot of people seem to just want to dismiss him outright and refuse to engage his movies beyond the tangible surface details (I’m thinking of Sucker Punch especially—an unfairly maligned feminist parable that was unjustly dismissed as meaningless eye-candy). Well, that’s their loss, as far as I’m concerned. Even so, Zack Snyder has proven to be one of those widely divisive filmmakers; people seem to love him or hate him; there isn’t a lot of traffic down the middle that I’ve observed.

The haters will probably have little use for this movie, as writer-producer Snyder’s fingerprints are all over it; one suspects his partnership with director Noam Murro is of the Spielberg-Hooper or Wachowski-McTiegue variety. And while Murrow himself is a fine stand-in for Zack Snyder circa 2006 (he certainly does a much better Snyder impression than the hapless Renny Harlin tried to do with the abominable Hercules: The Legend Begins [already gone and forgotten] a couple of months ago), that isn’t to say that Murrow disappears entirely or doesn’t bring anything to the table. While it would be easy to cynically label Rise of an Empire as a carbon-copy of 300; more-of-the-same, as it were—it actually represents a subtle evolution.

Noam Murro on the set of 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE

When 300 hit the box office in 2006 like Spartan shields smashing against Persian infantry, it spawned several pale imitations, weak facsimiles, and even a few gormless parodies that are best left forgotten to the sands of time. One of the biggest transgressions to come out of the glut of imitations was the gratuitous over-use of “speed-ramping,” a type of slow-motion effect in which the capture frame rate of the camera changes during a shot, producing a time-manipulation effect in which real-time and slow-motion blend together. Like “bullet-time” in the early 2000’s, speed-ramping has been played-out ad nauseum over the last eight years (Snyder himself contributed to this over-use with speed-ramping in Watchmen and Sucker Punch, although to be fair, it was kind of his signature style before everyone else co-opted it), which is probably why Zack Snyder refused to use the effect in Man of Steel last year. Most journeyman filmmakers seem to want to use it to simply make their action look “cool,” or even to pad out the running time (I strongly suspected Renny Harlin of this in his dopey Hercules movie). But when used properly, speed-ramping can serve to quickly orient the viewer in the midst of chaos, giving you enough time to process the visual information in front of you before plunging you back in the heat of the action—therefore achieving the emotional effect of experiencing the bedlam of what’s transpiring on screen without sacrificing the geography of the scene.

Unfortunately, most of the imitators seemed content to just use the technique without regard for what it should be used for, like a toddler swinging his dad’s hammer around willy-nilly. Nevertheless, there were a few properties that stood out amongst the lesser copies, taking inspiration from Snyder’s comic-book opus as a foundation from which to launch their own viable creative endeavor. I’m thinking primarily of the Starz series Spartacus and the video game series God of War. Although the influences of Frank Miller and Zack Snyder were evident in both of those properties, they took it and ran with it and did something unique. Spartacus adopted the hypperrealistic and impressionistic painterly elements of the production design, along with the speed-ramping action (used more properly this time around), and added political intrigue along with a sizable dose of vulgarity added to the language—think “Shakespeare in the Locker Room,” as if the words of the Bard inter-cut with every curse word, swear word, and dirty oath in the book. God of War, although released a full year before 300 the movie, likely drew inspiration from the graphic novel itself—if nothing else, then in the look of the game and the hyper-violence (also, the main character is a Spartan). Nevertheless, as the series went on, subsequent sequels certainly showed the influence of Snyder’s film, along with other movies like Clash of the Titans.

Rise of an Empire now brings that meta-cycle of inspiration full-circle. Although this movie is certainly stylistically consistent with the original 300, I can only surmise that the Frank Miller influence is much less this time around—I won’t know for sure until the unreleased Xerxes graphic novel (which this movie is based on) is published, but the cinematography and framing are much less comic-bookish than Snyder’s film, which, like Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City, used Miller’s panels as storyboards and reproduced the pages of the comic book on the screen. So not only does Rise of the Empire further distance itself from Miller; it allows itself to be influenced by the best of what both Spartacus and God of War have to offer. There’s even some Game of Thrones influence thrown in there for good measure, and why not? After all, television is much more compelling, influential, and artistically viable now than it was even a mere eight years ago.

The serial pay-cable television influenced is most strongly felt in the political machinations and especially the dialogue in specific respect to Spartacus—this time around, the high classical dialect of 300 has been dialed down a bit to make room for a more brusque and guttural type of naturalistic speaking—I don’t recall any f-bombs in 300, for example, but there’s definitely a few here, used to great effect. Rise of an Empire doesn’t go quite as far as Spartacus in this regard, but the influence is definitely there. As for God of War, this influence is felt most in the action sequences, which are definitely video game inspired (a common element of the action genre nowadays, or even to this series—300 had boss battles, after all—it’s no slight to either medium)—one of the more innovative techniques of the God of War boss battles was the combo-based combat which required players to execute a series of button combinations during slow-motion fighting sequences in order to deliver crippling combination attacks to the enemy. Rise of the Empire sneaks a few combo attacks in here and there, and they’re exhilarating to behold—and during the speed-ramping sequences—used for their proper effect and purpose here, orienting the viewer in the midst of chaotic battle—you can almost make out the button-prompts. If there’s one video-game element that hurts Rise of an Empire, it’s the ridiculous-looking CGI blood that flows like badly rendered wine—it’s incredibly distracting and looks dumber than hell, but when that’s my number-one complaint with your movie—something I’m willing to overlook, no less—I’d say you’re doing pretty well.

Part Hollywood History Lesson, part historical fantasy, Rise of an Empire earns the right to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with 300. Your mileage may vary as to whether or not you think it fares better or worse, but I’d challenge anyone who says they’re not in the same league.

[1] And may have shadow-directed this one as well—at the very least, it’s his vision on the screen

[2] All of this makes for a significantly more complicated story to follow than the straightforward A-B-C plot of the original. It’s the kind of thing that helped fell any goodwill the Star Wars prequels may have been able to muster, but darn it if Zack Snyder and Zack Snyder proxy Noam Murrow don’t make it work for them here.

[3] Let’s get her cast in “The Expendabelles” right away, okay?

[4] Three, if you count the “War on Terror.”

[5] In his review, Devin Faraci wisely points out that Artemisia’s origin story subverts and undercuts this historical falsehood.

[6] That is, war fought be flesh-and-blood human beings. We’re perfectly content to let drones bomb foreign landscapes into submission; even Nobel Peace Prize winner President Barack Obama has more than enough blood on his hands, having overseen more drone strikes than any other President in history in his role of Commander in Chief. But drone warfare was satirized in last month’s Robocop, so I’ll direct you to my review of that movie to discuss that issue further.